Even before the Internet, we’ve always been inside a hive mind of sorts, things have forever “gone viral” in one sense or another, though technology has made such functions more immediate, intricate and seamless. Of course, we’re only at the beginning. What becomes of us as individuals if our brains are always “plugged in” and we become a true neural collective, if our gray matter moves from “dial-up” to “broadband”? It will create new problems even as it helps solve many others.

A passage from “Hive Consciousness,” Peter Watts’ new Aeon essay:

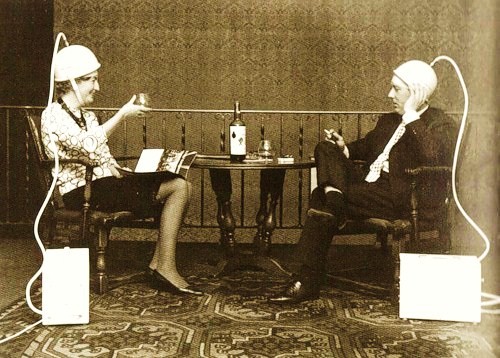

Cory Doctorow’s novel Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom(2003) describes a near future in which everyone is wired into the internet, 24/7, via cortical link. It’s not far-fetched, given recent developments. And the idea of hooking a bunch of brains into a common network has a certain appeal. Split-brain patients outperform normal folks on visual-search and pattern-recognition tasks, for one thing: two minds are better than one, even when they’re in the same head, even when limited to dial-up speeds. So if the future consists of myriad minds in high-speed contact with each other, you might say: Yay, bring it on.

I’m not sure that’s the way it’s going to happen, though.

I don’t necessarily buy into the hokey old trope of an internet that ‘wakes up’. Then again, I don’t reject it out of hand, either. Google’s ‘DeepMind’, a general-purpose AI explicitly designed to mimic the brain, is a bit too close to SyNAPSE for comfort (and a lot more imminent: its first incarnations are already poised to enter the market). The bandwidth of your cell phone is already comparable to that of your corpus callosum, once noise and synaptic redundancy are taken into account. We’re still a few theoretical advances away from an honest-to-God mind meld – still waiting for the ultrasonic ‘Neural Dust’ interface proposed by Berkley’s Dongjin Seo, or for researchers at Rice University to perfect their carbon-nanotube electrodes – but the pipes are already fat enough to handle that load when it arrives.

And those advances may come easier than you’d expect. Brains do a lot of their own heavy lifting when it comes to plugging unfamiliar parts together. A blind rat, wired into a geomagnetic sensor via a simple pair of electrodes, can use magnetic fields to navigate a maze just as well as her sighted siblings. If a rat can teach herself to use a completely new sensory modality – something the species has never experienced throughout the course of its evolutionary history – is there any cause to believe our own brains will prove any less capable of integrating novel forms of input?

Not even skeptics necessarily deny the likelihood of ‘thought-stealing technology.’•

Tags: Peter Watts