Figuring out the future of paid journalism isn’t just about making the economics work but by doing so while actually turning out original and intelligent reporting that has integrity. That’s something often lost on media analysts eager to bury the legacy of twentieth-century journalism, a mixed bag, sure, but an era that saw the best of reportage reach never-before-seen heights. We live in a fuller and deeper time because everyone is potentially a citizen journalist (a good thing), but we shouldn’t reflexively accept Buzzfeed and the like as the way forward simply because of page views or ad sales. From James King’s Gawker post, “My Year Ripping Off the Web With the Daily Mail Online“:

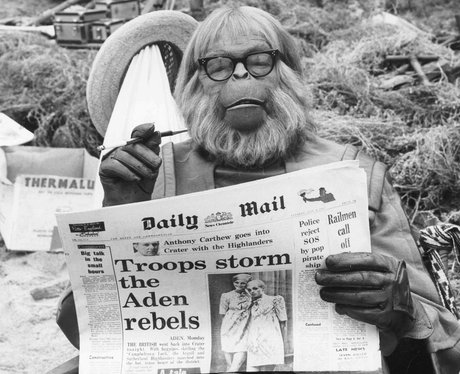

The eager paradigm-proclaimer Michael Wolff used his USA Today media column last August to praise the Mail’s business model as having succeeded where other, better-funded and more prestigious publications have failed. Under the headline “Daily Mail Solves Internet Paradox,” Wolff lauded the publication’s “180 million unique visitors a month” and suggested that if other publications want to survive the “digital migration” they should adopt a model similar to that of the Mail’s.

What Wolff failed to acknowledge: the Mail’s editorial model depends on little more than dishonesty, theft of copyrighted material, and sensationalism so absurd that it crosses into fabrication.

Yes, most outlets regularly aggregate other publications’ work in the quest for readership and material, and yes, papers throughout history have strived for the grabbiest headlines facts will allow. But what DailyMail.com does goes beyond anything practiced by anything else calling itself a newspaper. In a little more than a year of working in the Mail’s New York newsroom, I saw basic journalism standards and ethics casually and routinely ignored. I saw other publications’ work lifted wholesale. I watched editors at the most highly trafficked English-language online newspaper in the world publish information they knew to be inaccurate.

“We do things a little differently than you might be used to,” U.S. editor Katherine Thomson told me, early in my time there.

She was right. …

The production process was simple. During a day shift—8 a.m. to about 6 p.m—four news editors stationed together near Clarke’s desk assigned stories to reporters from a continually updated list of other publications’ articles, to which I did not have access. Throughout the day, they would monitor the website’s traffic to determine what was getting clicked on and what to remove from the homepage.

When a writer was free to write a story, he or she simply would shout “I’m free” and an editor would assign a link to an article on the list. In many cases, it would be accompanied by a sensationalized headline—one that may or may not have been accurate—for the writer to use.

During a typical 10-hour shift, I would catch four to seven articles this way. Unlike at other publications for which I’ve worked, writers weren’t tasked with finding their own stories or calling sources. We were simply given stories written by other publications and essentially told to rewrite them. And unlike at other publications where aggregation writers are encouraged to find a unique angle or to add some information missing from an original report, the way to make a story your own at the Mail is to pass off someone else’s work as your own.•

Tags: James King, Katherine Thomson