You could argue that Tunisia’s uprising was the match that lit the Middle East, as some struggles reverberate beyond their borders because they speak to a widespread dissatisfaction. The Paris Commune was viewed this way by outsiders during the late 1800s. Via the lovely Delancey Place, a passage from James Green’s Death in the Haymarket about the American interpretation of the French uprising:

When the French army laid siege to Paris and hostilities began, the Chicago Tribune’s reporters covered the fighting much as they had during the American Civil War. Many Americans, notably Republican leaders like Senator Charles Sumner, identified with the citizens of Paris who were fighting to create their own republic against the forces of a corrupt regime whose leaders had surrendered abjectly to the Iron Duke and his Prussian forces.

As the crisis deepened, however, American newspapers increasingly portrayed the Parisians as communists who confiscated property and as atheists who closed churches. The brave citizens of Paris, first described as rugged democrats and true republicans, now seemed more akin to the uncivilized elements that threatened America — the ‘savage tribes’ of Indians on the plains and the ‘dangerous classes’ of tramps and criminals in the cities. When the Commune’s defenses broke down on May 21, 1871, the Chicago Tribune hailed the breach of the city walls. Comparing the Communards to the Comanches who raided the Texas frontier, its editors urged the ‘mowing down’ of rebellious Parisians ‘without compunction or hesitation.’

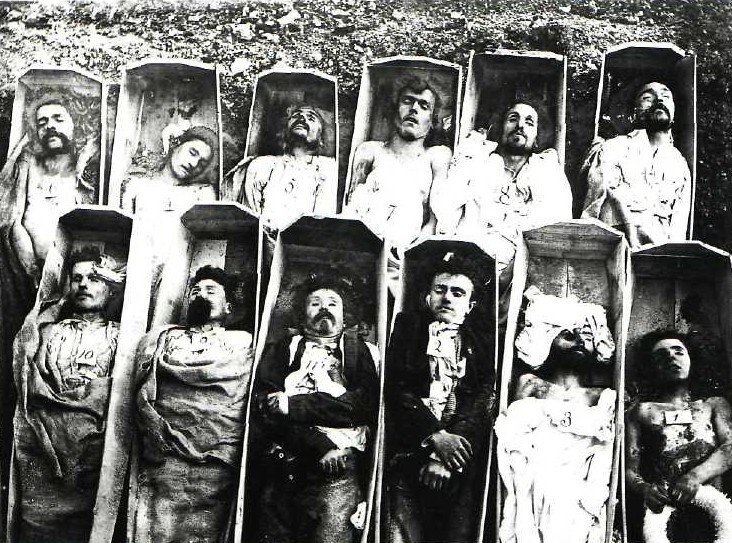

La semaine sanglante — the week of blood — had begun as regular army troops took the city street by street, executing citizen soldiers of the Parisian National Guard as soon as they surrendered. In retaliation, the Communards killed scores of hostages and burned large sections of the city to the ground. By the time the killing ended, at least 25,000 Parisians, including many unarmed citizens, had been slaughtered by French army troops.

These cataclysmic events in France struck Americans as amazing and distressing. The bloody disaster cried out for explanation. In response, a flood of interpretations appeared in the months following the civil war in France. Major illustrated weeklies published lurid drawings of Paris scenes, of buildings gutted by fire, monuments toppled, churches destroyed and citizens executed, including one showing the death of a ‘petroleuse’ — a red-capped, bare-breasted woman accused of incendiary acts. Cartoonist Thomas Nast drew a picture of what the Commune would look like in an American city. Instant histories were produced, along with dime novels, short stories, poems and then, later in the fall, theatricals and artistic representations in the form of panoramas.

News of the Commune seemed exotic to most Americans, but some commentators wondered if a phenomenon like this could appear in one of their great cities, such as New York or Chicago, where vast hordes of poor immigrants held mysterious views of America and harbored subversive elements in their midst.•

Tags: James Green