Apart from Las Vegas, few places in America have been enriched by casinos, since almost none become tourist destinations and they’re attended by a raft of costly social problems. Even the casinos on Native-American reservations, which enjoy special tax status, have shown mixed results at best and in many cases they may be increasing and further entrenching poverty. One issue might be per-capita payments, according to an Economist report. Perhaps. But the direct payments are often miniscule, so I’m not completely sold that’s it’s not more a toxic cocktail of complicated issues. An excerpt:

ON A rainy weekday afternoon, Mike Justice pushes his two-year-old son in a pram up a hill on the Siletz Reservation, a desolate, wooded area along the coast of Oregon. Although there are jobs at the nearby casino, Mr Justice, a member of the nearly 5,000-strong Siletz tribe, is unemployed. He and his girlfriend Jamie, a recovering drug addict, live off her welfare payments of a few hundred dollars a month, plus the roughly $1,200 he receives annually in “per capita payments”, cash the tribe distributes each year from its casino profits. That puts the family of three below the poverty line.

It is not ideal, Mr Justice admits, but he says it is better than pouring hours into a casino job that pays minimum wage and barely covers the cost of commuting. Some 13% of Mr Justice’s tribe work at the Chinook Winds Casino, including his mother, but it does not appeal to him. The casino lies an hour away down a long, windy road. He has no car, and the shuttle bus runs only a few times a day. “Once you get off your shift, you may have to wait three hours for the shuttle, and then spend another hour on the road,” he says. “For me, it’s just not worth it.”

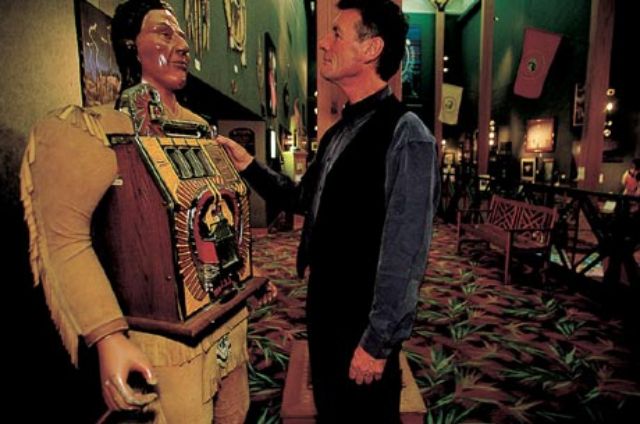

Mr Justice’s situation is not unusual. After the Supreme Court ruled in 1987 that Native American tribes, being sovereign, could not be barred from allowing gambling, casinos began popping up on reservations everywhere. Today, almost half of America’s 566 Native American tribes and villages operate casinos, which in 2013 took in $28 billion, according to the National Indian Gaming Commission.

Small tribes with land close to big cities have done well. Yet a new study in the American Indian Law Journal suggests that growing tribal gaming revenues can make poverty worse.•