Andrew McAfee and Eric Brynjolfsson’s The Second Machine Age, a deep analysis of the economic and political ramifications of Weak AI in the 21st century, was one of the five best books I read in 2014, a really rich year for titles of all kinds. I pretty much agree with the authors’ summation that there’s a plentitude waiting at the other end of the proliferation of automation fast approaching, though the intervening decades will be a serious societal challenge. In a post at his Financial Times blog, McAfee reconsiders, if somewhat, his reluctance to join in with the Hawking-Bostrom-Musk AI anxiety. An excerpt:

The group came together largely to discuss AI safety — the challenges and problems that might arise if digital systems ever become superintelligent. I wasn’t that concerned about AI safety coming into the conference, for reasons that I have written about previously. So did I change my mind?

Maybe a little bit. The argument that we should be concerned about any potentially existential risks to humanity, even if they’re pretty far in the future and we don’t know exactly how they’ll manifest themselves, is a fairly persuasive one. However, I still feel that we’re multiple “Watson and Crick moments” away from anything we need to worry about, so I haven’t signed the open letter on research priorities that came out in the wake of the conference — at least not yet. But who knows how quickly things might change?

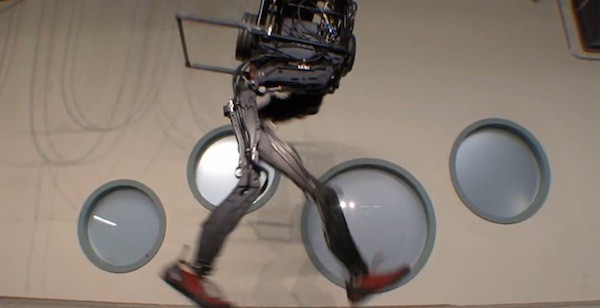

At the gathering, in answer to this question I kept hearing variations of “quicker than we thought.” In robotic endeavours as diverse as playing classic Atari video games,competing against the top human players in the Asian board game Go, creating self-driving cars, parsing and understanding human speech, folding towels and matching socks, the people building AI to do these things said that they were surprised at the pace of their own progress. Their achievements outstripped not only their initial timelines, they said, but also their revised ones.

Why is this? My short answer is that computers keep getting more powerful, the available data keeps getting broader (and data is the lifeblood of science), and the geeks keep getting smarter about how to do their work. This is one of those times when a field of human inquiry finds itself in a virtuous cycle and takes off.•

Tags: Andrew McAfee, Eric Brynjolfsson