Like much of the pre-Internet recording-industry infrastructure, the Columbia House Music Club, an erstwhile popular method of bulk-purchasing songs through snail mail, no longer exists, having departed this world before iTunes’ unfeeling gaze, as blank and pitiless as the sun. Your penny or paper dollar will no longer secure you a dozen records or tapes, nor do you have to experience the buyer’s remorse of one who reflexively purchases media without heeding the fine print which reveals that the relationship, as the Carpenters would say, had only just begun.

Of course, music pilfering didn’t start in our digital times with Napster, and Columbia was a prime target for those who loved systems capable of gaming. Via the excellent Longreads, here’s the opening of “The Rise and Fall of the Columbia House Record Club — and How We Learned to Steal Music,” a 2011 Phoenix article by Daniel Brockman and Jason W. Smith:

On June 29, 2011, the last remnant of what was once Columbia House — the mightiest mail-order record club company that ever existed — quietly shuttered for good. Other defunct facets of the 20th-century music business have been properly eulogized, but it seems that nary a tear was shed for the record club. Perhaps no one noticed its demise. After all, by the end, Columbia House was no longer Columbia House; it had folded into its main competitor and become an online-only entity years before.

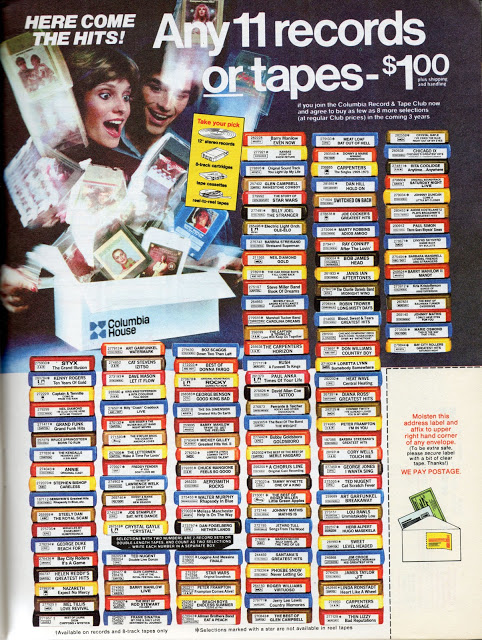

A more likely explanation, though, is that a new generation of music fans who had never known a world without the Internet couldn’t grasp the marvel that was the record club in its heyday. From roughly 1955 until 2000, getting music for free meant taping a penny to a paper card and mailing it off for 12 free records — along with membership and the promise of future purchasing.

The allure of the record club was simple: you put almost nothing down, signed a simple piece of paper, picked out some records, and voila! — a stack of vinyl arrived at your doorstep. By 1963, Columbia House was the flagship of the record-club armada, with 24 million records shipped. By 1994, they had shipped more than a billion records, accounted for 15 percent of all CD sales, and had become a $500-million-a-year behemoth that employed thousands at its Terre Haute, Indiana, manufacturing and shipping facility.

Of course, most of the record clubs’ two million customers failed to read the fine print, obligating them to purchase a certain number of monthly selections at exorbitant prices and even more exorbitant shipping costs. At the same time, consumers plotted to sign up multiple accounts under assumed names, in order to keep getting those 12-for-a-penny deals as often as possible. Record clubs may have introduced several generations of America’s youth to the concept of collection agencies — and the concept of stealing music, decades before the advent of the Internet.•

Tags: Daniel Brockman, Jason W. Smith