The American overreaction to Ebola, a real epidemic in Liberia but not here, probably has more to do with unstated anxieties than spoken ones. We’re in a globalized world now, on the cusp of a post-white country, in a time of technology and terrorism, invaders everywhere. Close the airports, strengthen the borders, quarantine the threats.

People have always tried to place a name to their fears, even if it was the wrong one. If you go back 100 to 150 years, life was commonly brutal and brief. Famine and disease and war were seemingly everywhere and knew no solution, treatment or permanent treaty. Anarchy was fashionable, science terrifying (“What hath God wrought!“), fascism about to rise and revolution in the air. The world seemed haunted. Even the “unsinkable” Titanic drank itself to death. Could some of that era’s carnage, even the shocking capsizing of that famous British passenger liner, have occurred because we had the temerity to disrupt nature’s order and aroused a mummy’s curse? Of course not, but sometimes the sick are not very circumspect of the diagnosis. From Rose Eveleth’s Nautilus piece “The Curse of the Unlucky Mummy“:

“Sometime in the 1860s, five recent Oxford graduates took a trip to Egypt. Together they sailed down the Nile, a tourist attraction even then. To remember their trip, they bought a souvenir in the mummy pits of Deir el-Bahri—the coffin lid of a priestess of Amen-Ra. The high priests of Amen-Ra, named after an Egyptian deity, were military rulers who commanded southern Egypt in the 21st Dynasty (1085 to 945 B.C.), a time of turmoil and strife. Powerful and prone to keep secrets, the priesthood worked to appease the gods that Egypt had clearly angered. With her wide, baleful eyes, open palms, and outstretched fingers, the priestess on the coffin lid seemed to cast a malevolent allure.

On their way back from Egypt, two of the men died. A third went to Cairo and accidentally shot himself in the arm while quail hunting and had to have it amputated. Another member of the group, Arthur Wheeler, managed to make it back to England, only to lose his entire fortune gambling. He moved to America and lost his new fortune to both a flood and a fire. The coffin lid was then placed under the care of Wheeler’s sister, who attempted to have it photographed in 1887. The photographer died, as did the porter. The man asked to translate the hieroglyphs on the lid committed suicide. The coffin lid seemed almost certainly cursed. But this was only the beginning.

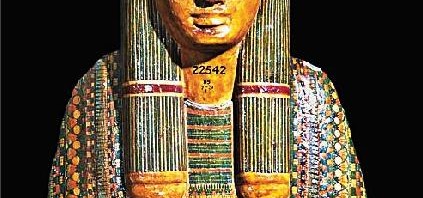

Today, the 5-foot-tall ‘mummy board’ lives in the British Museum, where it’s officially known as ‘artifact 22542.’ The mummified priestess that may have lain beneath it has been lost to eternity. But it has another, more commonly used name: ‘Unlucky Mummy.’ Since its arrival at the museum in 1889, the Unlucky Mummy has been blamed for everything from the sinking of the Titanic to the escalation of World War I. How this piece of wood become so intimately and persistently connected with death and destruction is a story of the endlessly swirling tales that people tell when they are afraid—of change, of politics, of science. It is the kind of story that never dies, only feeds upon itself, updating and morphing and tightening its grip no matter how much light is thrown on it.

By the time the Unlucky Mummy arrived at the British Museum, its reputation had seeped through British private society. While the museum curators generally scoffed at the alleged curse, men at soirees, dinner parties, and ‘ghost clubs,’ traded stories of its powers. But it wasn’t until 1904 that the broader public got a whiff of the curse. That was the year that a young, dashing, and ambitious journalist named Bertram Fletcher Robinson published a front-page article in the Daily Express, called ‘A Priestess of Death,’ about the allegedly haunted mummy. ‘It is certain that the Egyptians had powers which we in the 20th century may laugh at, yet can never understand,’ he wrote.

Three years later, Robinson died suddenly of a fever, and his friends immediately thought of the mummy’s curse. ‘The very last time I saw him he told me a wonderful tale about a mummy which had caused the death of everybody who had to do with it,’ wrote Archibald Marshall, an English author and journalist.”

Tags: Archibald Marshall, Arthur Wheeler, Bertram Fletcher Robinson, Rose Eveleth