For productivity to increase, labor costs must shrink. That’s fine provided new industries emerge to accommodate workers, but that really isn’t what we’ve seen so far in the Technological Revolution, the next great bend in the curve, as production and wages haven’t boomed. It’s been the trade of a taxi medallion for a large pink mustache. More convenient, if not cheaper (yet), for the consumer, but bad for the drivers.

Perhaps that’s because we’re at the outset of a slow-starting boom, the Second Machine Age, or perhaps what we’re going through refuses to follow the form of the Industrial Revolution. Maybe it’s the New Abnormal. The opening of the Economist feature, “Technology Isn’t Working“:

“IF THERE IS a technological revolution in progress, rich economies could be forgiven for wishing it would go away. Workers in America, Europe and Japan have been through a difficult few decades. In the 1970s the blistering growth after the second world war vanished in both Europe and America. In the early 1990s Japan joined the slump, entering a prolonged period of economic stagnation. Brief spells of faster growth in intervening years quickly petered out. The rich world is still trying to shake off the effects of the 2008 financial crisis. And now the digital economy, far from pushing up wages across the board in response to higher productivity, is keeping them flat for the mass of workers while extravagantly rewarding the most talented ones.

Between 1991 and 2012 the average annual increase in real wages in Britain was 1.5% and in America 1%, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, a club of mostly rich countries. That was less than the rate of economic growth over the period and far less than in earlier decades. Other countries fared even worse. Real wage growth in Germany from 1992 to 2012 was just 0.6%; Italy and Japan saw hardly any increase at all. And, critically, those averages conceal plenty of variation. Real pay for most workers remained flat or even fell, whereas for the highest earners it soared.

It seems difficult to square this unhappy experience with the extraordinary technological progress during that period, but the same thing has happened before. Most economic historians reckon there was very little improvement in living standards in Britain in the century after the first Industrial Revolution. And in the early 20th century, as Victorian inventions such as electric lighting came into their own, productivity growth was every bit as slow as it has been in recent decades.

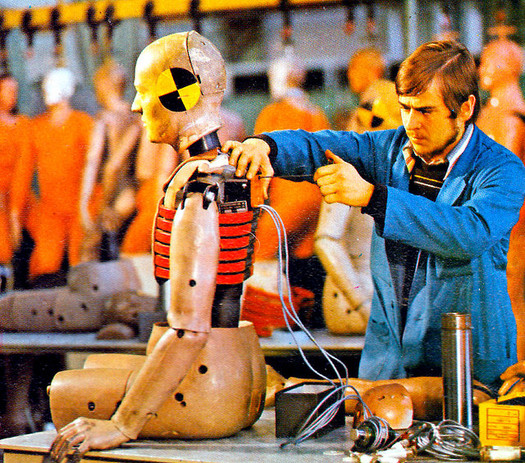

In July 1987 Robert Solow, an economist who went on to win the Nobel prize for economics just a few months later, wrote a book review for the New York Times. The book in question, The Myth of the Post-Industrial Economy by Stephen Cohen and John Zysman, lamented the shift of the American workforce into the service sector and explored the reasons why American manufacturing seemed to be losing out to competition from abroad. One problem, the authors reckoned, was that America was failing to take full advantage of the magnificent new technologies of the computing age, such as increasingly sophisticated automation and much-improved robots. Mr Solow commented that the authors, ‘like everyone else, are somewhat embarrassed by the fact that what everyone feels to have been a technological revolution…has been accompanied everywhere…by a slowdown in productivity growth.'”