Speaking of machines taking over, here’s one final excerpt from Nick Bostrom’s Superintelligence. It comes from one of the best passages, “Of Horses and Men.” The sequence I’m quoting is rather dire, though Bostrom later looks at the more positive side of technology handling labor for us and how extreme wealth disparity could be remedied. The excerpt:

“With cheaply copyable labor, market wages fall. The only place where humans would remain competitive may be where customers have a basic preference for work done by humans. Today, goods that have been handcrafted or produced by indigenous people sometimes command a price premium. Future consumers might similarly prefer human-made goods and human athletes, human artists, human lovers, and human leaders to functionally indistinguishable or superior artificial counterparts. It is unclear, however, just how widespread such preferences would be. If machine-made alternatives were sufficiently superior, perhaps they would be more highly prized.

One parameter that might be relevant to consumer choice is the inner life of the worker providing a service or product. A concert audience, for instance, might like to know that the performer is consciously experiencing the music and the venue. Absent phenomenal experience, the musician could be regarded as merely a high-powered jukebox, albeit one capable of creating the three-dimensional appearance of a performer interacting naturally with the crowd. Machines might then be designed to instantiate the same kinds of mental states that would be present in a human performing the same task. Even with perfect replication of subjective experiences, however, some people might simply prefer organic work. Such preferences could also have ideological or religious roots. Just as many Muslims and Jews shun food prepared in ways they classify as haram or treif, so there might be groups in the future that eschew products whose manufacture involved unsanctioned use of machine intelligence.

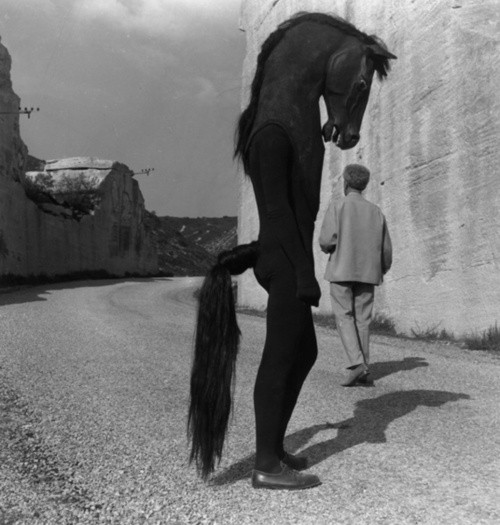

What hinges on this? To the extent that cheap machine labor can substitute for human labor, human jobs may disappear. Fears about automation and job loss are of course not new. Concerns about technological unemployment have surfaced periodically, at least since the Industrial Revolution; and quite a few professions have in fact gone the way of the English weavers and textile artisans who in the early nineteenth century united under the banner of the folkloric ‘General Ludd’ to fight against the introduction of mechanized looms. Nevertheless, although machinery and technology have been substitutes for many particular types of human labor, physical technology has on the whole been a complement to labor. Average human wages around the world have been on a long-term upward trend, in large part because of such complementarities. Yet what starts out as a complement to labor can at a later stage become a substitute for labor. Horses were initially complemented by carriages and ploughs, which greatly increased the horse’s productivity. Later, horses were substituted for by automobiles and tractors. These later innovations reduced the demand for equine labor and led to a population collapse. Could a similar fate befall the human species?

The parallel to the story of the horse can be drawn out further if we ask why it is that there are still horses around. One reason is that there are still a few niches in which horses have functional advantages; for example, police work. But the main reason is that humans happen to have peculiar preferences for the services that horses can provide, including recreational horseback riding and racing. These preferences can be compared to the preferences we hypothesized some humans might have in the future, that certain goods and services be made by human hand. Although suggestive, this analogy is, however, inexact, since there is still no complete functional substitute for horses. If there were inexpensive mechanical devices that ran on hay and had exactly the same shape, feel, smell, and behavior as biological horses — perhaps even the same conscious experiences — then demand for biological horses would probably decline further.

With a sufficient reduction in the demand for human labor, wages would fall below the human subsistence level. The potential downside for human workers is therefore extreme: not merely wage cuts, demotions, or the need for retraining, but starvation and death. When horses became obsolete as a source of moveable power, many were sold off to meatpackers to be processed into dog food, bone meal, leather, and glue. These animals had no alternative employment through which to earn their keep. In the United States, there were about 26 million horses in 1915. By the early 1950s, 2 million remained.”

Tags: Nick Bostrom