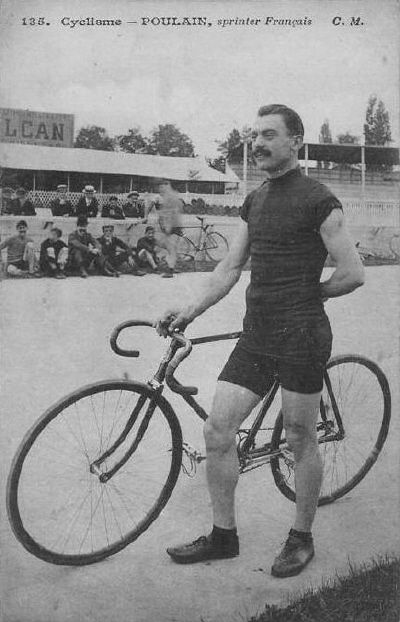

A small plane powered for a matter of feet by a person on a bicycle is utterly useless in a practical sense, yet achingly beautiful to admire. From a July 10, 1921 New York Times article about French wheelman Gabriel Poulain, who was a pioneer in this odd endeavor:

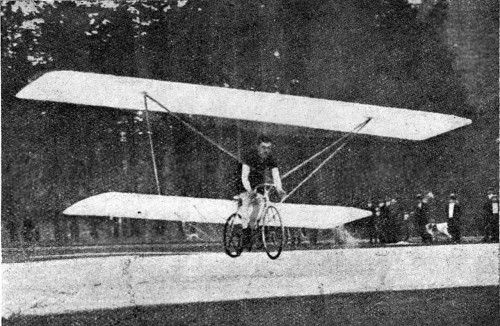

“Paris–Gabriel Poulain, the French champion cyclist, succeeded this morning in the Bois de Boulogne in winning the Peugot prize of 10,000 francs for the flight of more than ten meters distance and one meter high in a man-driven airplane. In an ‘aviette,’ which is a bicycle with two wing planes, he four times flew the prescribed distance, his longest flight being more than twelve meters, or about the same number of yards.

Poulain for several years has been devoting himself to the solution of the problem of flight by the power of his own muscles and several times has come near winning a prize. This morning’s exhibition, however, was by far the most successful, a cyclist never before having been able to rise from the ground a sufficient height to enable him to cover more than six or seven meters.

For today’s attempt Poulain altered the angle of the small rear plane of his machine and it was this alteration, it seems, that solved the problem.

Poulain made his attempt just after dawn on the smooth road at the entrance to the Longchamps race course. Several members of the Aero Club, donors of the prize and a large company of journalists and photographers were present. A square twenty meters each away was carefully measured off and chalked so as to mark the points at which the ‘aviette’ must rise one meter from the ground and that two flights must be made in opposite directions.

Rides Smoothly in Air

Poulain, who was confident that this time he was going to succeed, rode his machine at top speed toward the chalked square. As he entered it he released the clutch which throws the wing into proper position and at once the miniature biplane rose from the ground gracefully and steadily to a height of more than a meter.

The flight was as steady as that of a motor-driven airplane and Poulain declared afterward that the motion was smoother than when traveling along the ground. When the judges measured the distance between the wheel marks on the chalk they found it lacked only two centimeters of being twelve meters.

Poulain’s flight in the opposite direction was not quite so successful, though he succeeded in covering eleven and a half meters. In landing he broke two spokes of the rear wheel.

M. Robert Peugeot declared the prize won, but Poulain wished to make further proof of the powers of his machine. After changing the wheel he started from positions chosen by the judges, and in each case he succeeded in covering the prize-winning distance. His longest flight was the last, of twelve meters thirty-two centimeters.

In order to cover so great a distance Poulain worked up to a speed of forty-five kilometers an hour on the ground. According to his own estimate, the muscular force required for flight is equal to three horse power. The total weight of the machine, with the wings, is seventeen kilogrammes, or about thirty-seven pounds, and the cyclist himself weighs seventy-four kilograms, or about 165 pounds.

After the flight Poulain declared that he intended to set at work at once on another plane, which, he believes, will enable him to fly 200 to 300 meters. On this machine he will make use of a propeller instead of depending, as he did today, simply on impetus.

Once in the air, Poulain says that not so much power is needed as for the take-off. He says the pedal-worked propeller will be strong enough to continue flight for a considerable distance without fatigue.”