Harold Robbins wrote literature most suitable for the beach and for masturbation, though it’s probably best for readers to choose one or the other. In typical bluster from his heyday, the wet-dream merchant used a 1974 People article by Sandra Hochman to dismiss Roth, Bellow, Mailer and Hemingway, though the racy writer did speak fondly of Steinbeck, Dickens and Dumas. The article’s opening:

Harold Robbins steps off the plane at La Guardia Airport dressed like a California cowboy. Tall and tough-looking, he is wearing a tan cashmere jacket, silk printed shirt open at the chest, tight brown pants, a $3,000 Patek Philippe watch and white-embroidered brown boots, which are on one-inch platforms. He is as subtle and unpretentious as a character from one of his own steamy novels.

His press agent arrives in a blue limousine crammed with shopping bags which contain copies of Robbins’ new book, The Lonely Lady. Robbins and his wife ride out to the Air France terminal at Kennedy Airport. Grace Robbins, who is at least his third wife—he says only that he’s had “many”—is striking. She is all in white. Her shoes are wooden wedgies, even higher than his.

They are both easygoing, smiling. At Air France, their party is hustled to the VIP area of the first-class lounge. It is a circular, red-carpeted nook that has fake flowers on the coffee table, a white leatherette couch and a huge hanging silver lamp that looks like a hair dryer. The best-selling author in the world and his consort settle themselves comfortably for a short wait on their journey to France and home.

Printed on the inside of Harold Robbins’ paperbacks is the claim: “Every day, around the world, 25,000 people buy a Robbins novel.” That’s 9,125,000 books a year, counting Sundays; it may well be true. His dozen previous novels have topped the best-seller list. Lonely Lady, his 13th, will too. All told, Robbins’ books have sold more than 135 million copies. In a world where few writers ever find their way to the top, Robbins lives there.

No credit is due critics and purists, who usually consider Robbins’ lettres to be less than belles and delight in saying so. A 1974 New York Times review of The Pirate said, “Robbins is more a product than a writer and is marketed as relentlessly as a vaginal deodorant spray.” Reviews of The Lonely Lady so far have damned it with the faint praise of “good entertainment.” But who’s to say his work won’t be among the most remembered literature of our time? One person’s laundry list is another person’s poetry.

Robbins politely asks a lounge attendant for Playboy and Hustler to be sent over from a newsstand. He needs them, he explains, because he is researching a new book. The hero will be a skin magazine publisher, perhaps a composite of Hugh Hefner and Bob Guccione and others in that trade.

Robbins courteously orders drinks. There is talk about a big party which will take place in Cannes. Robbins seems indifferent. It is to be a combination birthday-promotion party for the movie version of The Pirate, the first film that Robbins is producing independently. But Robbins hates parties, even his own, which are frequent.

Harold Robbins writes about street people who hurl themselves against a hostile society and either become cosmically rich and powerful—or abjectly fall apart and are corrupted. This contrast between good and evil has led many readers to place Robbins’ work in the category of morality tales. His affinity for explicit and kinky sex scenes has led other readers to dismiss it as pornography.

Now 60, Robbins did not start writing novels until he was in his 30s, but then his formula emerged full-blown: Take a famous person who is or has been in the public subconscious—Howard Hughes (The Carpetbaggers) or auto executive Henry Ford (The Betsy) or, with his current novel, Peyton Place author Grace Metalious. (Robbins says The Lonely Lady is not Jacqueline Susann, as some reviewers have speculated.) Create a persona in fiction that is an exaggeration of the celebrity. Jumble together action, narrative drive, bitter pragmatism, sex, exotic locales, accurate observation of small details and energetic street language.

Robbins certainly knows the hard-times-to-lap-of-luxury tales he deals with; whether writing about the hucksterism of Hollywood, the rackets of the jet set, the con men on the streets and in large corporations or the poverty of a kid on the Lower East Side, Robbins has some life research he can put into his novels.•

____________________________

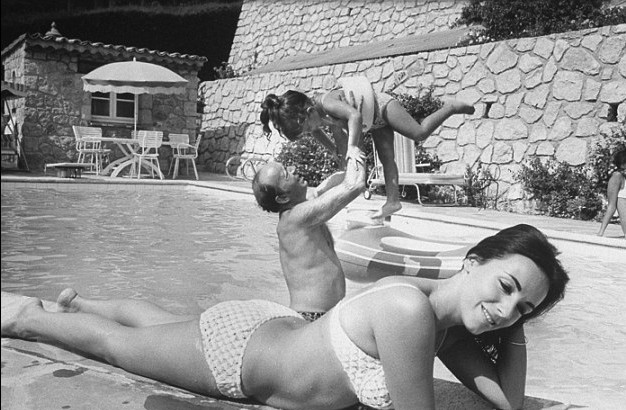

“People who have it all and want more,” 1969:

Tags: Harold Robbins, Sandra Hochman