I’m sticking with my non-scientific analysis that so many baseball pitchers are getting injured and requiring Tommy John surgery because they’re simply overthrowing. When I was a kid, you would have a Nolan Ryan here or there who could very easily bring a hellacious fastball, but most of the pitchers were able to succeed with more finesse than force. With the injuries piling up and today’s focus on defensive shifting and a pitch-to-defense philosophy, you would think teams would start to lay off the throwers who are clearly going full-tilt on every pitch and have likely been doing so since they were in grade school. Let’s just hope Masahiro Tanaka won’t be added to the growing list of TJ-surgery alumni.

One devastating pitch was shelved almost league-wide over the last several decades because it was thought unfriendly to the arm. From “The Mystery of the Vanishing Screwball,” Bruce Shoenfeld’s New York Times Magazine article about the pitch that dare not be thrown:

“A pitcher’s typical menu includes a fastball, a curveball and a changeup as the meat and potatoes, with perhaps a slider, cut fastball or sinker as a side. The screwball is another dish entirely. Those who serve one have typically been looked upon as oddities, custodians of a quirky art beyond the realm of conventional pitching. Over time, the word itself has taken on the characteristics of both the pitch and those who throw it: erratic, irrational or illogical, unexpected. Unlike the knuckleball, which is easy to throw but hard to master, the screwball requires special expertise just to get it to the plate. The successful screwball pitcher must overcome an awkward sensation that feels like tightening a pickle jar while simultaneously thrusting the wrist forward with extreme velocity. Yet the list of master practitioners includes some of baseball’s greats: Christy Mathewson, Carl Hubbell, Warren Spahn, Juan Marichal.

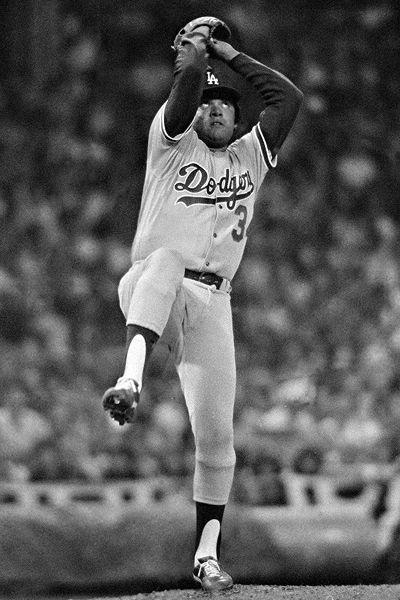

In 1974, Mike Marshall of the Los Angeles Dodgers won the National League’s Cy Young Award by relying on the screwball. Tug McGraw used it to get to three World Series as a reliever with the Mets and Phillies. In 1984, Detroit’s screwballer, Willie Hernandez, was both the American League’s top pitcher and Most Valuable Player. The last great practitioner was Fernando Valenzuela, most famously a Dodger, who threw a wide assortment of pitches, none more prominent — or effective — than his screwball.

Today few, if any, minor leaguers are known to employ the pitch. College coaches claim they haven’t seen it in years. Youths are warned away from it because of a vague notion that it ruins arms. ‘Pitchers have given it up,’ says Don Baylor, the former player and manager, who now works with Angels hitters. ‘Coaches don’t even talk about it. It’s not in the equation.’

Many of baseball’s best hitters have never seen a screwball. This spring, I spent time in nearly a dozen clubhouses asking about the pitch. ‘Maybe in Wiffle ball,’ David Freese, the Angels’ third baseman, said. ‘But I’ve never sat in a hitters’ meeting and heard, ‘This guy’s got a screwball.’ It doesn’t come up. I’m not sure I even know exactly what it is.’

As a result, the pitch has taken on somewhat mythical properties.”

Tags: Bruce Shoenfeld