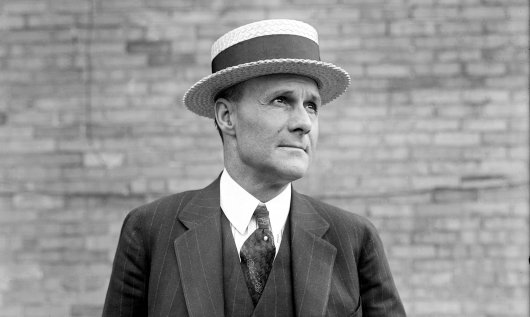

Even in death, Tex Rickard knew how to give them a show. The “them” in this case would be the admiring public who showed up in the tens of thousands to the wake of the boxing promoter, which was held in the ring area of Madison Square Garden. He was most famous for being the honest fight promoter who wouldn’t allow fixes or mismatches, whose affiliation with Jack Dempsey helped create the first million-dollar gates and who, in 1921, brought boxing to American radio audiences for the first time, introducing sports to mass media. But Rickard’s life went far beyond organized fisticuffs. He built both MSG (the third iteration) and Boston Gardens, he was a Texas marshal, an Alaska gold prospector, a gambling hall and bar proprietor, a longtime friend of Wyatt Earp, and the founder and first owner of the NHL’s New York Rangers. The grand man was sadly felled by an appendectomy gone bad a few days after his fifty-ninth birthday.

Even in death, Tex Rickard knew how to give them a show. The “them” in this case would be the admiring public who showed up in the tens of thousands to the wake of the boxing promoter, which was held in the ring area of Madison Square Garden. He was most famous for being the honest fight promoter who wouldn’t allow fixes or mismatches, whose affiliation with Jack Dempsey helped create the first million-dollar gates and who, in 1921, brought boxing to American radio audiences for the first time, introducing sports to mass media. But Rickard’s life went far beyond organized fisticuffs. He built both MSG (the third iteration) and Boston Gardens, he was a Texas marshal, an Alaska gold prospector, a gambling hall and bar proprietor, a longtime friend of Wyatt Earp, and the founder and first owner of the NHL’s New York Rangers. The grand man was sadly felled by an appendectomy gone bad a few days after his fifty-ninth birthday.

From the January 9, 1929 Brooklyn Daily Eagle article about his final “show”:

“In the center of the great arena of Madison Square Garden, that Tex Rickard’s showmanship built, the body of the fight promoter lay in state today while the thousands who had admired him in life filed by in silence for a final view of Tex Rickard in death.

Seventy-five or more a minute they passed the bronze casket under a blanket of red and white flowers. One line to the left and one to the right. One from the 49th St. entrance and the other from 50th St. Five thousand passed and looked in the first hour, 10,000 by noon, some 30,000 before the funeral service began at 2 p.m. The Rev. Caleb Moor, pastor of the Madison Avenue Baptist Church, officiated. The burial was to follow in Woodlawn Cemetery, the Bronx.

Actresses in sable coats, longshoremen, washwomen, policemen, bankers, lawyers, children in arms, millionaires, paupers, racetrack touts, Broadway hangers-on, ministers of the Gospel…it was a strange double procession that turned out toward the 8th Ave. exit or melted away in silence among the seats there to wait for the formal services later on.

Never before had this Madison Square Garden, Rickard’s own ‘temple of sports,’ seen such a phenomenon, and no doubt will never again.

Here had been skeptical crowds, enthusiastic crowds, cheering crowds, savage crowds that snarled and called for blood. Here had been lights and gongs sounding, jazz orchestras playing, the thud of leather against human jaws, the clink of skates on the hockey ice, the whirl of six-day bicycle racers. Today dim lights pierced the shadows up there near the roof, and from the tiny windows came streaks of shadowy daylight that only added to the dark.

$15,000 Casket

The body of Rickard, in immaculate evening clothes, lay in the $15,000 bronze casket on a slightly raised platform in the very center of what had been the prize fighting ring, the rink of the hockey players. From the shoulders down nothing was visible but the roses–roses, red and white. At the casket’s head stood Sgt. Timothy Murphy, longtime friend of the promoter, at a straight and stern attention, without moving muscle as the hours dragged by. Motionless as Rickard himself.

Clustered palms formed a sort of green cathedral nave around the altar on which were the remains of the man who had risen from Texas cow puncher to a world figure. And in dimness nothing else was visible except the spot of green, the dull, motley moving files, the flowers, the somber purple and the black splotches of crepe and here and there the bright blue uniform of a Garden attendant.

And for sound, only the shuffling feet of thousands of silent mourners.

Outside the crowd grew and grew. There had been perhaps 5,000 when the doors were thrown open shortly after 10 a.m. A bit of unruliness developed then when the mounted police in an effort to line the mourners up in twos rode up on the sidewalks. Soon this quieted down. By twos and twos they formed thereafter, beginning at the side entrances and extending gradually out to 8th Ave., to 9th and to 10th. Shortly after midday some 15,000 were waiting to follow those who had already entered.

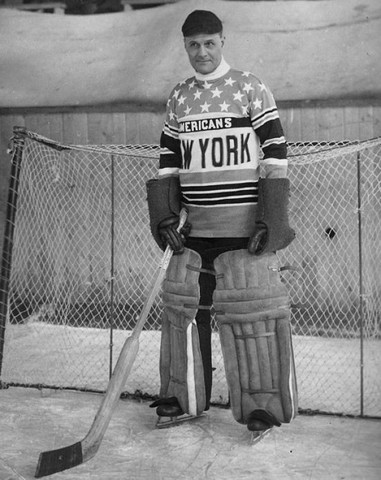

Earlier in the morning the young Mrs. Rickard had come in with Jack Dempsey and Walter Field, assistant and close friend of the dead man. They sat down beside the casket. For a brief interval there, alone with these two men in the amphitheater, Mrs. Rickard wept over her dead. There was a gigantic piece of carnations and forget-me-nots from the employees of the Garden. The New York Rangers, Rickard’s own hockey team, sent a huge wreath, and their rivals, the Americans, offered another. … Many of the big dealers in New York found themselves stripped of flowers before midnight as a steady stream of orders poured in. Smaller dealers were asked to contribute and did. And all night long, even into this morning, huge pieces of floral offerings were being carried into the cavernlike old Garden, which had suddenly become a glimmering, brilliant bed of beauty.

Draped in Beauty

The Garden entrance was draped in black. Inside there were patches of black. Inside, however, were the flowers, and all the somberness of the crepe could not take away their brilliance. They said that even the Valentino funeral, which brought thousands of floral pieces, did not approach the Rickard ceremony.”

Tags: Jack Dempsey, Rev. Caleb Moor, Sgt. Timothy Murphy, Tex Rickard