What do you think of the protests in Brazil? Is hosting the World Cup good for the people of Brazil in the long run?

Franklin Foer:

Over the past decade, the Brazilian middle class has exploded. A broad swath of the population has been lifted from poverty. This is a great thing and an amazing accomplishment of Lula’s party, the PT. But the new middle class has very sensible concerns about the expenditure of public money. They are asking very wise questions about a ridiculous 11 billion price tag; they aren’t falling for the old bread-and-circus routine. I don’t foresee the protests in Brazil spinning violently out of control. In the long run, this tournament isn’t great for Brazil. It highlights the country’s shortcomings, rather than affirming its greatness. I wish the Brazilians had focused their infrastructure planning and expenditure on a more limited number of cities and venues. This would have contained costs and created a greater likelihood of success.”

____________________________

From The New Republic:

“Over time, Brazil grew dangerously dependent on soccer. It came to define the nation in the eyes of the world, and it played an outsized role in its own sense of self-worth. Victories came so easily during the ’60s and ’70s that the country didn’t just demand trophies; they wanted those triumphs procured with what Freyre called Futebol Arte and what the world knows as Jogo Bonito, the beautiful game. As one coach of the national team complained, ‘It got to the point where we beat Bolivia 6-0 and one newspaper in São Paulo accused us of playing defensively.’

The almost unbearable pressure on managers inevitably led the team away from improvisational genius. The tactics used to win the 1994 World Cup—perhaps the worst World Cup of them all—squelched inventiveness and favored the deployment of pragmatic hard men, who had a greater skill at knocking opponents off the ball than running at them with step-over dribbling.

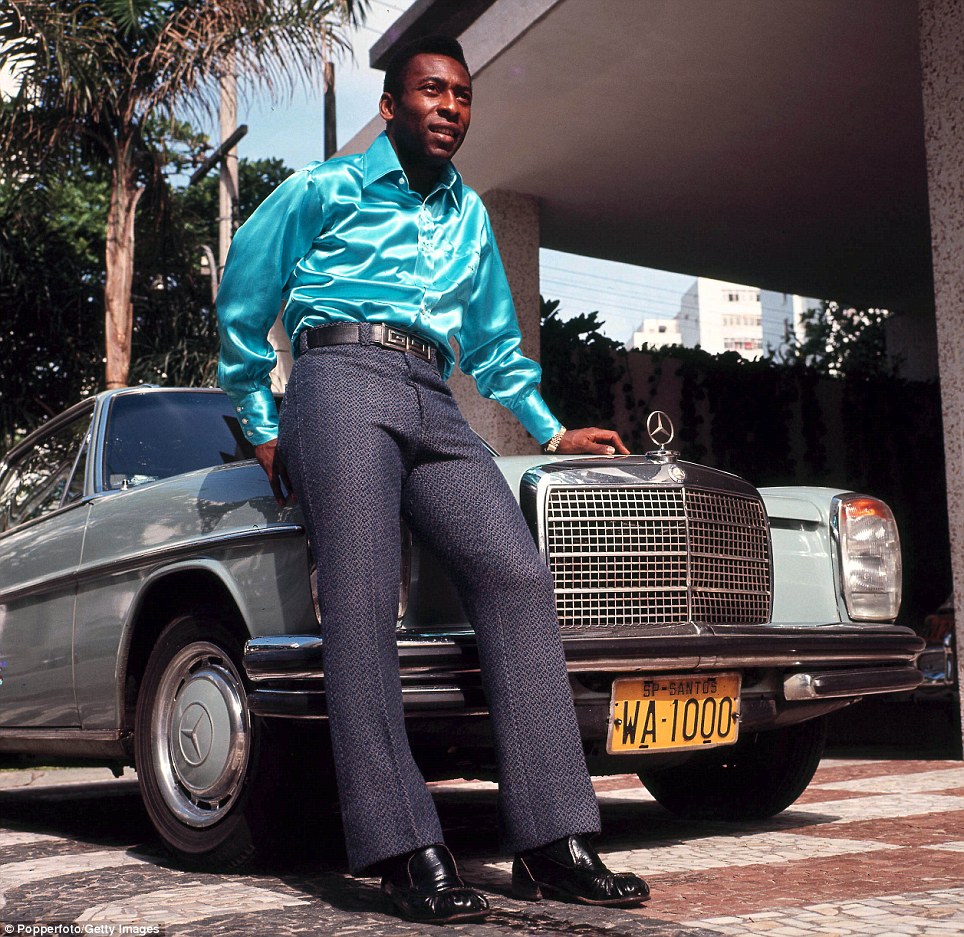

And there was a far graver cost to success than that. Dictators and aspiring dictators skillfully harnessed mass enthusiasm for the game. Getúlio Vargas, the authoritarian leader who presided from 1930 to 1945, explicitly used soccer to create a new sense of national identity, a campaign of brasilidade, or Brazilization—and to ballast his own power. He built stadiums, then held rallies in them. His successors mimicked this approach. During the reign of the military dictatorship in the ’70s, the government plastered Pelé’s face on posters alongside its slogan: ‘NOBODY CAN STOP THIS COUNTRY NOW.’

Pelé, it should be remembered as you watch him in commercials for Subway’s $5 foot-long, didn’t just lend his visage to the cause; he spoke up on behalf of the dictatorship. ‘We are a free people. Our leaders know what is best for [us],’ he said in 1972. At that very moment, the writer David Zirin has noted, Brazil’s current president, Dilma Rousseff, was being tortured in prison.”