I put up a post just a couple of weeks ago about Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, and since then it’s quickly become an unlikely blockbuster, sold out in brick-and-mortar stores and ranked #1 on Amazon, the latest green shoot in the Occupy mindset which blossomed in these scary financial times. At Foreign Affairs, economist Tyler Cowen provides a well-written review of the work, which he finds impressive but (unsurprisingly) disagrees with in fundamental ways. The opening:

“Every now and then, the field of economics produces an important book; this is one of them. Thomas Piketty’s tome will put capitalist wealth back at the center of public debate, resurrect interest in the subject of wealth distribution, and revolutionize how people view the history of income inequality. On top of that, although the book’s prose (translated from the original French) might not qualify as scintillating, any educated person will be able to understand it — which sets the book apart from the vast majority of works by high-level economic theorists.

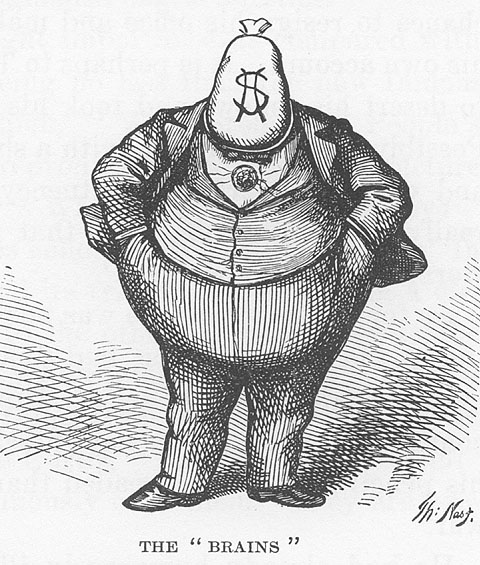

Piketty is best known for his collaborations during the past decade with his fellow French economist Emmanuel Saez, in which they used historical census data and archival tax records to demonstrate that present levels of income inequality in the United States resemble those of the era before World War II. Their revelations concerning the wealth concentrated among the richest one percent of Americans — and, perhaps even more striking, among the richest 0.1 percent — have provided statistical and intellectual ammunition to the left in recent years, especially during the debates sparked by the 2011 Occupy Wall Street protests and the 2012 U.S. presidential election.

In this book, Piketty keeps his focus on inequality but attempts something grander than a mere diagnosis of capitalism’s ill effects. The book presents a general theory of capitalism intended to answer a basic but profoundly important question. As Piketty puts it:

‘Do the dynamics of private capital accumulation inevitably lead to the concentration of wealth in ever fewer hands, as Karl Marx believed in the nineteenth century? Or do the balancing forces of growth, competition, and technological progress lead in later stages of development to reduced inequality and greater harmony among the classes, as Simon Kuznets thought in the twentieth century?’

Although he stops short of embracing Marx’s baleful vision, Piketty ultimately lands on the pessimistic end of the spectrum. He believes that in capitalist systems, powerful forces can push at various times toward either equality or inequality and that, therefore, ‘one should be wary of any economic determinism.’ But in the end, he concludes that, contrary to the arguments of Kuznets and other mainstream thinkers, ‘there is no natural, spontaneous process to prevent destabilizing, inegalitarian forces from prevailing permanently.’ To forestall such an outcome, Piketty proposes, among other things, a far-fetched plan for the global taxation of wealth — a call to radically redistribute the fruits of capitalism to ensure the system’s survival. This is an unsatisfying conclusion to a groundbreaking work of analysis that is frequently brilliant — but flawed, as well.”

Tags: Thomas Piketty, Tyler Cowen