From “Trick of the Eye,” Iwan Rhys Morus’ wonderful Aeon essay about the nature and value of optical illusions:

“People who said that they saw ghosts really did see them, according to Brewster. But they were images produced by the (deluded) mind rather than by any external object: ‘when the mind possesses a control over its powers, the impressions of external objects alone occupy the attention, but in the unhealthy condition of the mind, the impressions of its own creation, either overpower, or combine themselves with the impressions of external objects’. These ‘mental spectra’ were imprinted on the retina just like any others, but they were still products of the mind not the external world. So ghosts were in the eye, but put there by the mind: ‘the ‘mind’s eye’ is actually the body’s eye’, said Brewster.

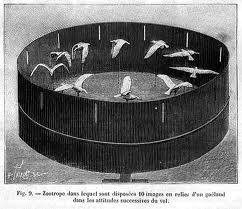

Seeing ghosts demonstrated how the mind-eye co-ordination that generated vision could break down. Philosophical toys such as phenakistiscopes and zoetropes — which exploited the phenomenon of persistence of vision to generate the illusion of movement — did the same thing. The thaumatrope, first described in 1827 by the British physician John Ayrton Paris, juxtaposed two different images on opposite sides of a disc to make a single one by rapid rotation — ‘a very striking and magical effect’. A popular Victorian version had a little girl on one side, a boy on the other. They were positioned so that their lips met in a kiss when the disc rotated.

The daedaleum (later renamed the zoetrope), invented in 1834 by the mathematician William George Horner, was ‘a hollow cylinder … with apertures at equal distances, and placed cylindrically round the edge of a revolving disk’ with drawings on the inside of the cylinder. The device produced ‘the same surprising play of relative motions as the common magic disk does when spun before a mirror’. (The ‘magic disk’ was the phenakistiscope, invented a few years earlier by the Belgian natural philosopher Joseph Plateau). In the zoetrope, the viewer looked through one of the slits in the rotating cylinder to see a moving image — often, a juggling clown or a horse galloping. In the phenakistiscope, they looked through a slit in the rotating disc to see the moving image reflected in a mirror. Faraday, too, experimented with persistence of vision.

The daedaleum (later renamed the zoetrope), invented in 1834 by the mathematician William George Horner, was ‘a hollow cylinder … with apertures at equal distances, and placed cylindrically round the edge of a revolving disk’ with drawings on the inside of the cylinder. The device produced ‘the same surprising play of relative motions as the common magic disk does when spun before a mirror’. (The ‘magic disk’ was the phenakistiscope, invented a few years earlier by the Belgian natural philosopher Joseph Plateau). In the zoetrope, the viewer looked through one of the slits in the rotating cylinder to see a moving image — often, a juggling clown or a horse galloping. In the phenakistiscope, they looked through a slit in the rotating disc to see the moving image reflected in a mirror. Faraday, too, experimented with persistence of vision.

Brewster’s kaleidoscope was another philosophical toy that fooled the eye. Brewster described it as an ‘ocular harpsichord’, explaining how the ‘combination of fine forms, and ever-varying tints, which it presents in succession to the eye, have already been found, by experience, to communicate to those who have a taste for this kind of beauty, a pleasure as intense and as permanent as that which the finest ear derives from musical sounds’. The kaleidoscopic illusion was supposed to teach the viewer how to see things properly; it was also, interestingly, meant to be a technology that could mechanise art. It ‘effects what is beyond the reach of manual labour’, said Brewster, exhibiting ‘a concentration of talent and skill which could not have been obtained by uniting the separate exertions of living agents.’“

Tags: Iwan Rhys Morus