In Ian Thomson’s Financial Times piece about Claudia Roth Pierpoint’s new Philip Roth book, he includes a brief passage about the Roth-Primo Levi relationship. That segment mentions a 1986 New York Times article Roth write about Levi. A passage from each follows.

From Thomson:

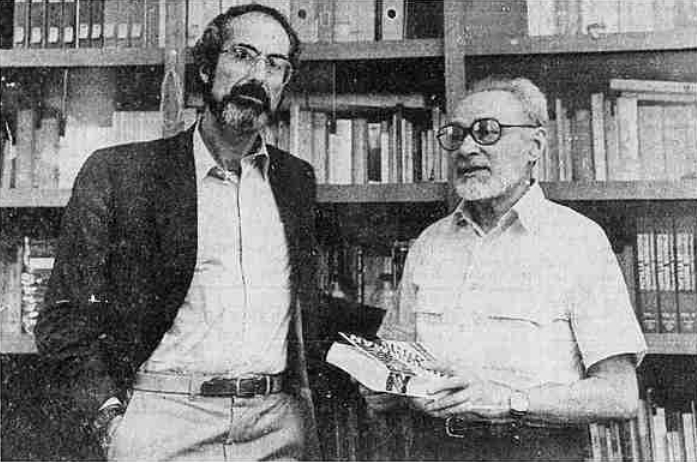

“Roth met Levi in the spring of 1986. If Levi was unprepared for Roth’s engagingly gentle presence, Roth found Levi surprisingly sociable. (‘With some people you just unlock,’ Roth recalled.) As they said goodbye outside the Italian Cultural Institute in London, Levi told Roth: ‘You know, this has all come too late.’ The encounter nevertheless proved to be one the most important in 20th-century literature. Roth afterwards interviewed Levi for the New York Times and helped to consolidate Levi’s reputation across the Atlantic. Accompanied by Bloom, Roth had called on Levi in September 1986 at the paint and varnish factory outside Turin where he had worked as an industrial chemist. The staff were warned not to mention Portnoy’s Complaint, as Roth was apparently no longer so fond of his ‘masturbation novel.’

Seven months later, Levi was dead. The effect on Roth of Levi’s suicide in 1987 was ‘staggering.’ Roth told Pierpont, adding: ‘It hit me like the assassinations of the sixties.’ Although Roth had cultivated friendships with other European writers, notably Ivan Klíma and Milan Kundera, his friendship with Levi, Pierpoint says, had gone ‘remarkably deep.'”

_______________________

From “A Man Saved By His Skills,” by Roth:

“ON the September Friday that I arrived in Turin – to renew a conversation with Primo Levi that we had begun one afternoon in London the spring before – I asked to be shown around the paint factory where he’d been employed as a research chemist and, afterwards, until retirement, as factory manager. Altogether the company employs 50 people, mainly chemists who work in the laboratories and skilled laborers on the floor of the plant. The production machinery, the row of storage tanks, the laboratory building, the finished product in man-sized containers ready to be shipped, the reprocessing facility that purifies the wastes – all of it is encompassed in four or five acres a seven-mile drive from Turin. The machines that are drying resin and blending varnish and pumping off pollutants are never really distressingly loud, the yard’s acrid odor – the smell, Levi told me, that clung to his clothing for two years after his retirement – is by no means disgusting, and the skip loaded with the black sludgy residue of the antipolluting process isn’t particularly unsightly. It is hardly the world’s ugliest industrial environment, but a very long way, nonetheless, from those sentences suffused with mind that are the hallmark of Levi’s autobiographical narratives. On the other hand, however far from the prose, it is clearly a place close to his heart; taking in what I could of the noise, the stench, the mosaic of pipes and vats and tanks and dials, I remembered Faussone, the skilled rigger in The Monkey’s Wrench, saying to Levi – who calls Faussone ‘my alter ego’ – ‘I have to tell you, being around a work site is something I enjoy.’

On our way to the section of the laboratory where raw materials are scrutinized before moving on to production, I asked Levi if he could iden-tify the particular chemical aroma faintly permeating the corridor: I thought it smelled a little like a hospital corridor. Just fractionally he raised his head and exposed his nostrils to the air. With a smile he told me, ‘I understand and can analyze it like a dog.’

He seemed to me inwardly animated more in the manner of some little quicksilver woodland creature empowered by the forest’s most astute intelligence. Levi is small and slight, though not quite so delicately built as his unassuming demeanor makes him at first appear, and still seemingly as nimble as he must have been at 10. In his body, as in his face, you see – as you don’t in most men – the face and the body of the boy that he was. His alertness is nearly palpable, keenness trembling within him like his pilot light.”

Tags: Claudia Roth Pierpoint, Ian Thomson, Philip Roth, Primo Levi