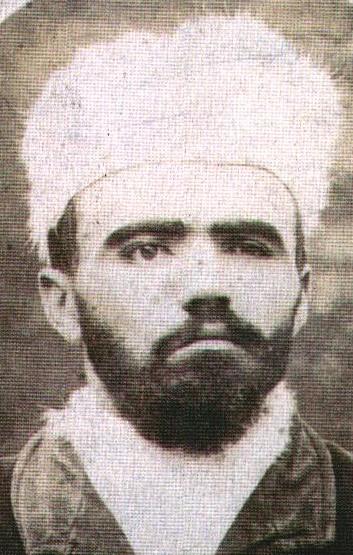

“This desperate criminal was notoriously vain, and fancied himself a hero.”

French serial killer Joseph Vacher didn’t deny his atrocities–he just refused culpability for them, assigning blame to God. He was no doubt brain damaged from one or other mishaps in his life and had almost a Leibnizian optimism for his brutal crimes. From an article in the January 1, 1899 New York Times at the time of his execution:

“Paris–Joseph Vacher, the French ‘Jack the Ripper,’ was guillotined at Bourg-en-Bresse, capital of the Department of Ain, this morning. He protested his innocence and simulated insanity to the last. Vacher, who was twenty-nine years of age, was condemned in October at the Ain Assizes.

______

The crimes of Joseph Vacher have surpassed in number and atrocity those of the Whitechapel murderer known as ‘Jack-the-Ripper.’ His homicidal mania first broke out seriously in 1894. He claimed, after his arrest, that as every action has an object, and as his motive neither theft nor vengeance, his irresponsibility was established He one day told a Magistrate that he considered himself a scourge sent by Providence to afflict humanity. It was claimed in his defense that when a youth he was bitten by a mad dog, and that the village herbalist gave him some medicine, after drinking which he became strange, irritable and brutal, whereas he had previously been quiet and inoffensive. It also appears from these statements that from that time he developed a passion for human blood. It was also shown that Vacher had been confined in an asylum for the insane, and that a love affair once caused him to attempt self-destruction by shooting.

Referring to his crimes, Vacher is quoted as saying, ‘My victims never suffered, for while I throttled them with one hand I simply took their lives with a sharp instrument in the other.’ I am an Anarchist, and I am opposed to society, no matter what the form of government may be.’

This desperate criminal was notoriously vain, and fancied himself a hero. He refused to speak about his crimes except on two conditions. One was that the full story of his murders be published in the leading French papers, and the other was that he should be tried separately for each crime in the district where it was committed.

The exact number of Vacher’s victims will never be known, but, it is said that twenty-three murders had been brought home to him in October last, and the number was added to as time went on. In fact, it is doubtful whether the murderer himself knew the real number of his victims. Many persons whom he attacked narrowly escaped being killed.

Born near Lyons, Vacher served his military term in a regiment of Zouaves, and showed himself to be a good soldier, so much so that he was made a non-commissioned officer, although there were complaints against him of being brutally severe to recruits. It was shortly after he left the service that he attempted to kill himself. The bullet was never abstracted from his skull, and, according to reports the wound produced recurrent fits of insanity, and caused him to be confined in an insane asylum at Dole. The physicians, however, released him because they were afraid of an outcry in the press against the arbitrary confinement of a citizen, although the physicians were well aware that he was not in a condition to be at large.

Since that time and until his arrest Vacher appears to have wandered through the country districts of France, leaving a trail of blood behind him. He was undetected and unsuspected until, by mere accident, he was caught almost redhanded near Lyons at the beginning of October.

One of the remarkable features of this extraordinary case was the clever manner in which Vacher succeeded in shifting suspicion from himself. About two years ago he murdered a shepherd boy on a country road a few miles from Lyons, hacked the body almost into pieces, and then continued on his way. The murder was discovered within a few minutes afterward, and search for the murderer was promptly instituted in all directions, with a result that a gendarme, mounted on a bicycle, overtook Vacher, and called upon him to produce his identification papers, whereupon Vacher quietly handed over to the police officer his discharge as a non-commissioned officer from a regiment of zouaves.

‘Why, this is my old regiment!’ exclaimed the gendarme. ‘I am hunting for a man who has just cut a boy’s throat. Have you seen any suspicious character?’

‘Oh, yes,’ answered the murderer serenely. ‘I saw a man running across the fields to the north, about a mile back from here.’

‘Thank you!’ cried the gendarme. ‘I’ll be after him,’ The gendarme then hurried off after the imaginary murderer, and the real culprit stole away from the scene of the crime.

By lucky chances, some of Vacher’s would-be victims escaped him. For instance, a boy, thirteen years of age, named Rodier, was herding cows near Clermont Ferrand one day in October a year ago, when he saw an ugly-looking, grinning tramp approach him, carrying a big bag on his back and a heavy stick in his hand. The boy was alarmed and as the stranger came nearer Rodier ran away. The same afternoon Vacher attacked three other women in the same manner, and they all escaped him as Mme. Marchand did.

The most prominent victim of Vacher was the Marquis of Villeplaine, who was killed while walking in his park in the southwestern part of France, not far from the Spanish frontier. Vacher crept up behind him, felled him with a heavy stick, and then cut his throat. The murderer carried off the coat of the Marquis, and the pocketbook containing some bank notes. He then sought refuge in Spain.”

Tags: Joseph Vacher