Robbing graves to supply medical schools with cadavers is as old as the dissecting table itself, but the ransoming of famous corpses began in earnest in America when an attempt was made to disinter President Lincoln’s remains from his final resting place. A report from the March 13, 1888 Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

Within the last ten years there has arisen a phase of grave robbing against which the law in its present form seems to provide but poorly. Previously the operations of grave robbers had been confined to procuring subjects for the dissecting table, and it is for this class of crimes that the present laws are framed. They do not contemplate the union of shameful extortion to sacrilege in the form of grave robbing for the purpose of obtaining ransom.

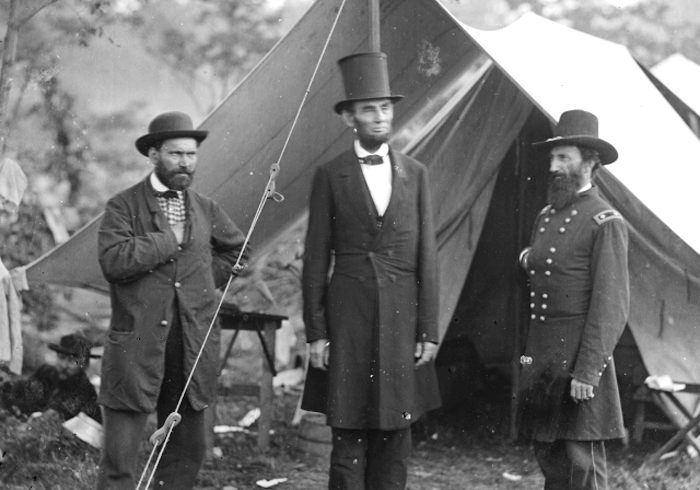

Of late years the plundering of cemeteries and vaults with this purpose has become of such frequency that it is now deemed prudent, if not necessary, to place a guard over the grave of every person of wealth or distinction immediately after burial. This kind of grave robbing began in this country in 1876, with an attempt to steal the body of President Lincoln from its resting place in Springfield, Ill. It was the purpose of the conspirators to hold the body for a ransom of $250,000, together with the pardon of a noted counterfeiter to whom they were friendly. The success of the scheme was happily thwarted by the confusion of one of the confederates.

Two years later a like attempt made on the body of A.T. Stewart, of New York, was more successful. The details of this robbery are still remembered. The body has been recovered by the family, but at what cost is not accurately known. Those concerned in the plot have never been apprehended. These well known cases serve to indicate the good reasons for the precautions taken in the protection of the bodies of ex-President Grant, of William H. Vanderbilt and more recently of Mrs. John Jacob Astor.

By way of showing to what extent the law is powerless in such cases, it is of interest to cite the theft of the body of Earl Crawford, in Scotland, in 1882. On the arrest of one of the perpertrators of this outrage it was found that there was no statute more applicable to this case than that for the punishment of sacrilege. No penalties for robbery could be imposed, since a dead body could not be regarded at law as property.

The maximum penalty prescribed by the public statutes of our State for criminal grave robbing is imprisonment not exceeding three years, or by fine not exceeding $2,000. The whole chapter of which this section forms a part has for its subject the preservation of chastity, morality, decency and good order. It is true that it is no more an offense to steal the body of a rich man than it is to steal the body of a poor man, yet there is in the former case an additional element which finds an additional punishment in the eyes of the law. It would seem that but just that in cases where extra inducement in the hope of extortion exists, extra penalties should be imposed; for sacrilege may remain mercifully unknown to the relatives of the dead, but grave robbing, with the aim of extorting ransom, cruelly wounds the hearts of the living and is one of the most shameful forms of plunder.•