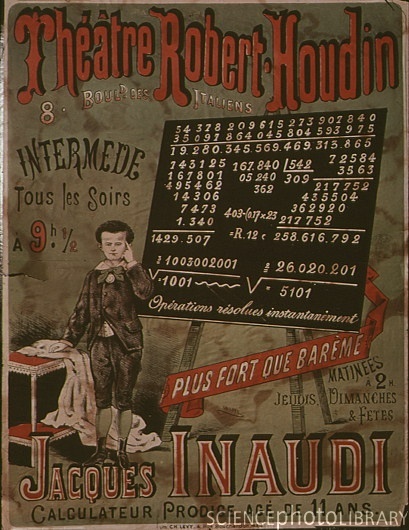

So-called “Lightning Calculators” were sideshow performers more than a century ago who could solve complicated mathematical problems in their heads in front of live audiences. Few had the facility for numbers displayed by Jacques Inaudi (1867-1950), an Italian who toured extensively with vaudeville shows demonstrating his prodigious abilities. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle profiled the math man on October 15, 1901 (and misidentified his nationality). An excerpt:

“To make a real hit, mathematics in vaudeville have to be of a sensational character. The old time lightning calculator, with his demonstrations and short processes, would depreciate to the vanishing point if compared with Jacques Inaudi, ‘the man with the double brain,’ at the Orpheum this week. Inaudi is a Frenchman and his English is limited but there seem to be no limitation upon his ability to do wonders in arithmetic.

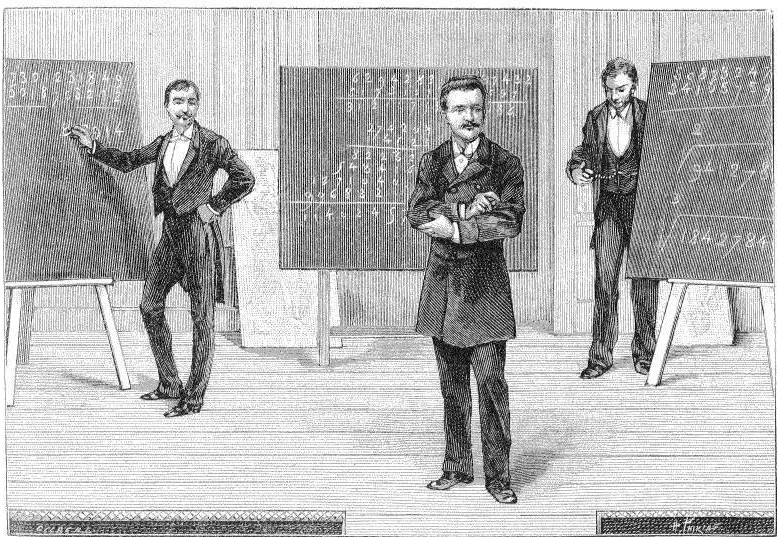

One blackboard isn’t enough for him; so his assistant operates five in a row. Ordinary examples apparently bore him; so, if given an option, he chooses something in the trillions. His assistant, who wears a big black mustache and a dress suit, has to work much harder, physically, than Inaudi. The latter, who faces the audience from a little projecting platform, never looks at the blackboard, but repeats the numbers given him from various parts of the house for his manager, and stage assistant, to write with Parisian flourishes. Then, when the sum in addition, subtraction, cube root or what not, is complete, the manager works it out in sight of the audience but, quick as he is, Monsieur Inaudi finished before him and gives the correct answer to the people in the front.

Last night Inaudi asked first for material for a sum in subtraction. Various three figure combinations were shouted here and there, with the result that when the top of the five boards had been filled to overflowing Inaudi had a proposition like this–not before–but behind him: Subtract 297, 122, 999, 492, 322, 260 from 495, 876, 711, 411, 460, 594. It was not the sort of a sum that the ordinary school sharp would care to tackle mentally, but Monsieur Inaudi did it, with his back turned to the board; and he did something else beside. This is where the double brain theory gained its notoriety. All the while that Inaudi was calculating in amounts rather more than the average man’s spending money, he was answering questions, as to the week days of certain dates, from anybody in the audience. Many men fired the date of their birth at him and received back instantly the day of the week. A glance at the questioner’s face was enough to indicate that Inaudi’s answer had been the right one.

In the meantime the hard working manager at the blackboard had been taking violent exercise in subtraction.

‘Haf you finished?’ asked Inaudi, from his place out by the footlights.

‘Non, non,’ was the answer, ‘It ees not quite.’

‘I haf finished,’ said Inaudi, calmly.

There, still looking straight ahead, the Frenchman gave the answer, the same as that which had been worked out on the blackboard: 98, 753, 711, 919, 138, 334. After that came multiplication, square root and finally Monsieur Inaudi repeated without a falter, from beginning to end, every figure that appeared on the blackboard up stage.

There, still looking straight ahead, the Frenchman gave the answer, the same as that which had been worked out on the blackboard: 98, 753, 711, 919, 138, 334. After that came multiplication, square root and finally Monsieur Inaudi repeated without a falter, from beginning to end, every figure that appeared on the blackboard up stage.

Inaudi and his manager were the very pink of politeness when an Eagle man saw them later in their dressing room. More tests in mathematics followed and with them every suspicion of possible treachery vanished.

‘What were you before making use of your ability at figures?’ the reporter asked.

‘Monsieur Inaudi was a shepherd,’ his manager replied for him, ‘a shepherd, with hees sheep, in France. One day, years, ago, he came to Marseilles. A strangaire there learned what he could do in mathematiques. He heard him and took him to Paree. Since then he has been before scienteests, doctairs and all–and all say, ‘Monsieur Inaudi ees a man with two brains.’

‘Have you got a memory for other matters like your memory for figures?’

‘It ees for feegures only,’ said Inaudi, answering for himself.”