The impetus for change in 1969’s Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice comes from two of the titular characters attending guerrilla psychological workshops at the Esalen Institute at Big Sur. Two years prior, Leo Litwak, the novelist, journalist and book reviewer, brought his considerable writing skills to the alternative-therapy retreat for a New York Times Magazine story. A section from “Joy Is the Prize” in which the author is awakened to a repressed memory from WWII:

I never anticipated the effect of these revelations, as one after another of these strangers expressed his grief and was eased. I woke up one night and felt as if everything were changed. I felt as if I were about to weep. The following morning the feeling was even more intense.

Brigitte and I walked down to the cliff edge. We lay beneath a tree. She could see that I was close to weeping. I told her that I’d been thinking about my numbness, which I had traced to the war. I tried to keep the tears down. I felt vulnerable and unguarded. I felt that I was about to lose all my secrets and I was ready to let them go. Not being guarded, I had no need to put anyone down, and I felt what it was to be unarmed. I could look anyone in the eyes and my eyes were open.

That night I said to Daniel: “Why do you keep diverting us with your intellectual arguments? I see suffering in your eyes. You give me a glimpse of it, then you turn it off. Your eyes go dead and the intellectual stuff bores me. I feel that’s part of your strategy.”

Schutz suggested that the two of us sit in the center of the room and talk to each other. I told Daniel I was close to surrender. I wanted to let go. I felt near to my grief. I wanted to release it and be purged. Daniel asked about my marriage and my work. Just when he hit a nerve, bringing me near the release I wanted, he began to speculate on the tragedy of the human condition. I told him: “You’re letting me off and I don’t want to be left off.”

Schutz asked if I would be willing to take a fantasy trip.

It was later afternoon and the room was already dark. I lay down, Schutz beside me, and the group gathered around. I closed my eyes. Schutz asked me to imagine myself very tiny and to imagine that tiny self entering my own body. He wanted me to describe the trip.

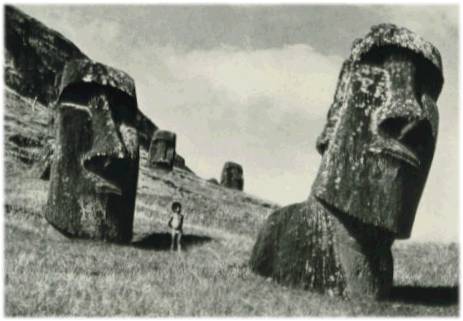

I saw an enormous statue of myself, lying in the desert, mouth open as if I were dead. I entered my mouth. I climbed down my gullet, entering it as if it were a manhole. I climbed into my chest cavity. Schutz asked me what I saw. “It’s empty,” I said. “There’s nothing here.” I was totally absorbed by the effort to visualize entering myself and lost all sense of the group. I told Schutz there was no heart in my body. Suddenly, I felt tremendous pressure in my chest, as if tears were going to explode. He told me to go to the vicinity of the heart and report what I saw. There, on a ledge of the chest wall, near where the heart should have been, I saw a baby buggy. He asked me to look into it. I didn’t want to, because I feared I might weep, but I looked, and I saw a doll. He asked me to touch it. I was relieved to discover that it was only a doll. Schutz asked me if I could bring a heart into my body. And suddenly there it was, a heart sheathed in slime, hung with blood vessels. And that heart broke me up. I felt my chest convulse. I exploded. I burst into tears.

I recognized the heart. The incident had occurred more than 20 years before and had left me cold.•

Tags: Leo Litwak, Will Schutz