Roger Ebert was one of the best newspaper writers ever–lucid, interesting, prolific, intelligent, inviting–in the same league as Breslin, Hamill or Royko. My interaction with him was minimal: I interviewed the critic once by phone and spoke to him another time at the Toronto festival about the Jessica Yu film, In the Realms of the Unreal, which we both loved. He was naturally argumentative and cantankerous but remarkably generous and open-minded and egalitarian and warm. And he was steadfastly progressive in regards to women and minorities, to people who didn’t have the kind of platform he had carved for himself. Ebert was truly the King of All Media, and I’m constantly amazed at how such an ink-stained wretch found his way not only through the world of television but through all areas of the new communication platforms.

The odd thing is that outside of his early years, Ebert had pretty lousy, hit-or-miss taste in film. He wasn’t a blurb whore like, say, Jeffrey Lyons (who used to loudly mock Ebert’s appearance in vicious, personal terms at New York screenings). He just lost his critical compass by the late 1970s. Sometimes Ebert’s aforementioned progressive politics seemed to get in the way of his critical eye: He disliked Blue Velvet in part because of how Isabella Rossellini’s character was treated, and he named Eve’s Bayou, a good film, the best film of 1997, the same year that saw the release of Boogie Nights, Fast, Cheap & Out of Control, L.A. Confidential, etc. But often he just seemed to make odd choices (e.g., hating Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man) that someone with his intelligence shouldn’t.

But if Ebert’s taste faltered, his writing and soul never, ever did. He was an amazing guy who left the world a better, smarter place because of his presence. He was loved and will be missed.

In the New York Times, David Carr, who is Ebert’s equal as a writer, examines the Chicagoan’s empire-building skills. The opening:

“At journalism conferences and online, media strivers talk over and over about becoming their own brand, hoping that some magical combination of tweets, video spots, appearances and, yes, even actual written articles, will help their name come to mean something.

As if that were a new thing.

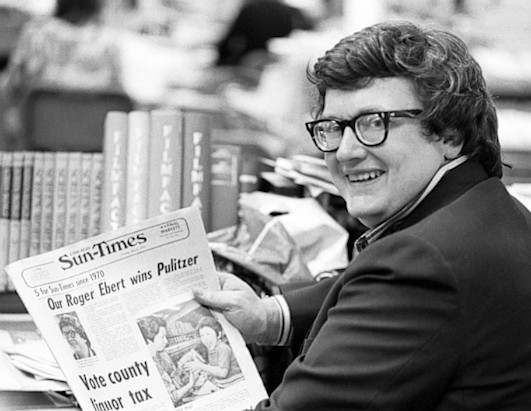

Since Roger Ebert’s death on Thursday, many wonderful things have been said about his writing gifts at The Chicago Sun-Times, critical skills that led to a Pulitzer Prize in 1975, the first given for movie criticism. We can stipulate all of that, but let’s also remember that a big part of what he left behind was a remarkable template for how a lone journalist can become something much more.

Mr. Ebert was, in retrospect, a very modern figure. Long before the media world became cluttered with search optimization consultants, social media experts and brand-management gurus, Mr. Ebert used all available technologies and platforms to advance both his love of film and his own professional interests.

He clearly loved newspapers, but he wasn’t a weepy nostalgist either. He was an early adopter on the Web, with a CompuServe account he was very proud of, and unlike so many of his ink-splattered brethren, he grabbed new gadgets with both hands.

But it wasn’t just a grasp of technology that made him a figure worthy of consideration and emulation.

Though he was viewed as a movie critic with the soul of a poet, he also had killer business instincts. A journalist since the 1960s, he not only survived endless tumult in the craft, he thrived by embracing new opportunity and expanding his franchise at every turn.”

Tags: David Carr, Roger Ebert