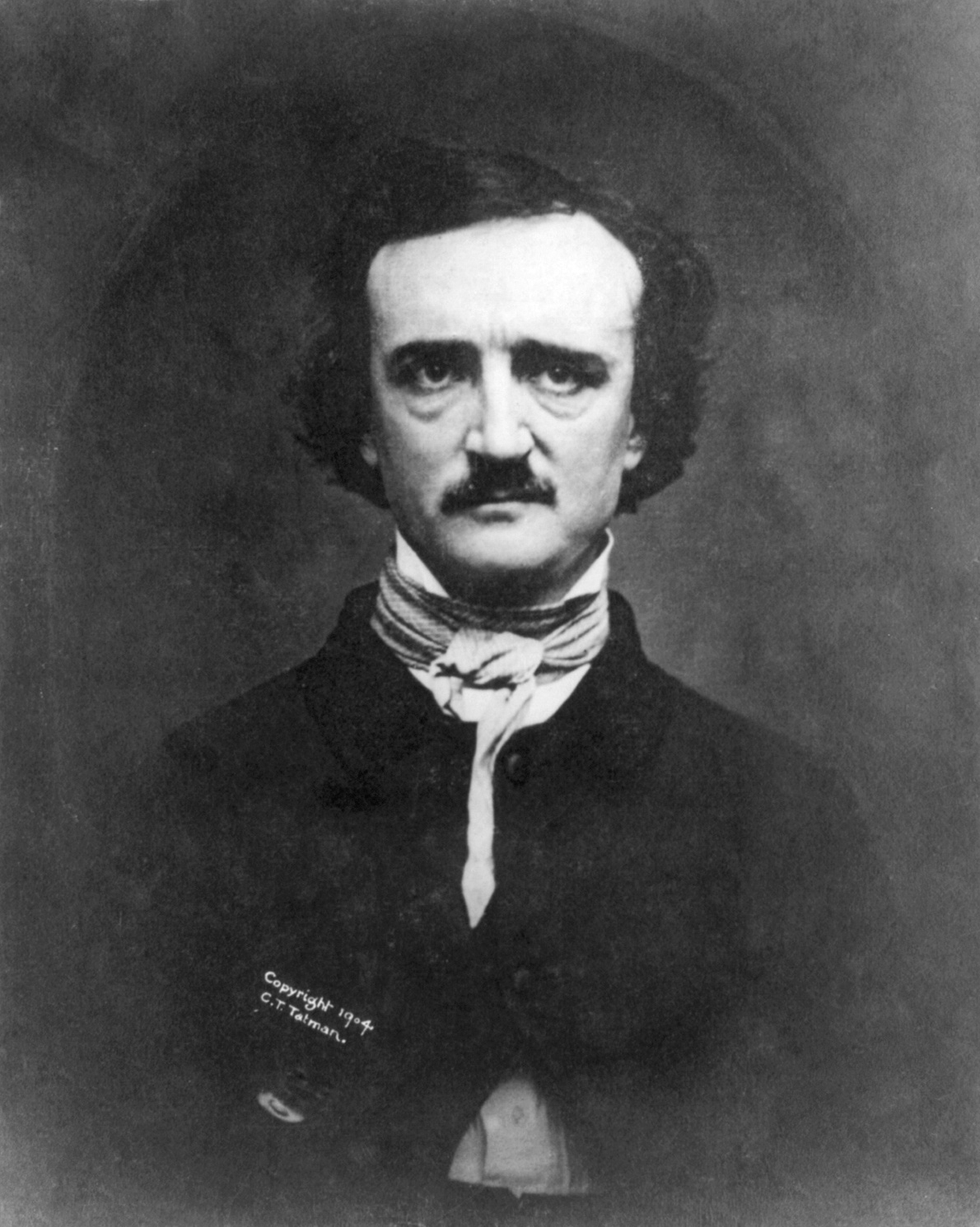

Fittingly, Edgar Allan Poe’s death was a mysterious one. The haunting author, the first American to try to make his living solely as a writer, was found disoriented, ranting and ragged on the streets of Baltimore on an autumn day in 1849. Nobody could tell what had put him in such a state at age 40, and he was taken to a hospital where he died a few days later. Was his puzzling death the result of drunkenness or rabies or murder? No one still knows for sure. Muddling matters even further was that Poe’s enemy, the editor Rufus Wilmot Griswold, somehow became the executor of his estate and did his best to sully the writer’s reputation, suggesting his end resulted from a dissolute lifestyle.

A January 20, 1907 New York Times article promised to make sense of the puzzle nearly six decades after the Poe’s tragic demise, asserting that scientific breakthroughs had made it possible to understand what killed the poet and short-story writer. The paper called on one of the finest alienists of the era to undertake the mission, though great clarity didn’t exactly result from the enterprise. The opening of “Edgar Allan Poe’s Tragic Death Explained“:

Edgar Allan Poe, the author of “The Raven,” “The Gold Bug,” and “The Murders of the Rue Morgue”–to name merely the most popular of his works–the writer whose power startled Dickens and excited the admiration of Irving, Lowell, and Browning, and whom Tennyson called “the most original genius that America has produced,” was found in the streets of Baltimore on Oct. 3, 1847 [sic], dazed, in rags, a physical and mental wreck. He lay for days unconscious or raving like a madman, then sank to death. His condition was ascribed to a debauch or drugs, or both, his pitiful end to mania-a-potu.

In his lifetime and since his death, Poe’s personal habits and the circumstance of his end have been the topics of endless discussion, in which vituperation has been mingled with vehement defense. He has been pictured as a transcendent genius and a drunkard, a polished gentleman and a surly misanthrope.

Within the last few weeks, the whole topic has been reopened by the approaching dedication of a monument to Poe in Richmond, Va. To the existing mass of contradictory testimony and discussion has been added much new material on the subject. Some of this, including letters, accounts of personal experiences, and the first article dealing with Poe’s case purely from the medical standpoint, has been published very recently. Taken as a whole, however, the evidence leaves the layman as much puzzled as ever regarding Poe’s complex personality and the circumstances of his death.

To arrive at the truth of the matter and to clear Poe’s name of injustice, if such existed, the New York Times has gathered all the evidence relating to the subject, particularly the letters and accounts recently printed, and submitted them to an alienist who ranks high as an authority on such matters in this city, and a physician whose practice particularly fits him to deal with the subject. This specialist undertook to review all of this evidence and to draw therefrom his conclusions regarding Poe as a man and his fatal malady.

The expert offered a surprising opinion. It contradicts the contention that Poe died of mania-a-potu. His death is traced to cerebral oedema, or “water on the brain” or “wet brain,” a disease unknown in the author’s day, but now well recognized with the advance of medical science. The more recent theories that Poe suffered from psychic epilepsy or paresis are discounted. Moreover the physician’s study of the case has resulted in the belief that the psychopathic phases of Poe’s case were so unusual that his mental responsibility is to be seriously questioned. His opinion follows:

“In reviewing the case of a man of undoubted genius, like Edgar Allan Poe, we must remember that Nature, while developing certain brain centres to an unusual degree, has neglected other mental attributes, so that they are far below those found in the average man. Thus Poe’s powers of imagination were abnormal at the expense of his will power, his ability to resist temptation, and his recuperation in case of misfortune. Such facts do not apply to men of exceptional abilities like Washington–abilities often confounded with genius–but to men of very exceptional gifts in only one direction. Lord Byron furnished an example of this condition. Its presence marked Poe as a weak man. His inherited characteristics were bad. His nervous system was constitutionally deranged; he was abnormal to a degree that leads one to seriously doubt his mental or moral responsibility. Add to these elements his reckless youth, the ease with which he was surrounded early in his life, and the years of poverty and misfortune which followed, and his tragic end is already foreshadowed.”•