This life is a fluid thing, as precise meaning is chased by algorithms, with no print books in sight. From a new NYT piece about the art of the auto-correct by information heavyweight James Gleick:

“When Autocorrect can reach out from the local device or computer to the cloud, the algorithms get much, much smarter. I consulted Mark Paskin, a longtime software engineer on Google’s search team. Where a mobile phone can check typing against a modest dictionary of words and corrections, Google uses no dictionary at all. ‘

A dictionary can be more of a liability than you might expect,’ Mr. Paskin says. ‘Dictionaries have a lot of trouble keeping up with the real world, right?’ Instead Google has access to a decent subset of all the words people type — ‘a constantly evolving list of words and phrases,’ he says; ‘the parlance of our times.’

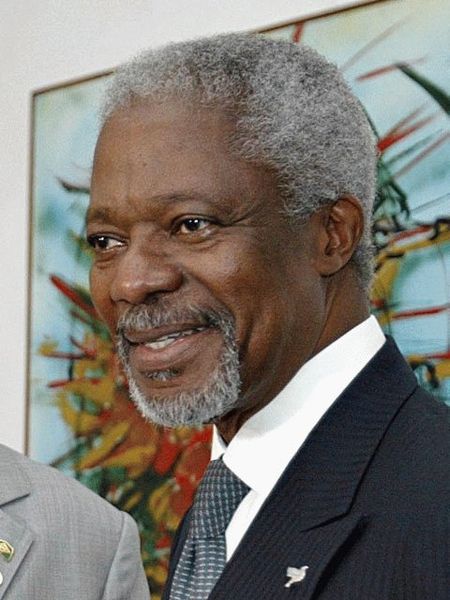

If you type ‘kofee’ into a search box, Google would like to save a few milliseconds by guessing whether you’ve misspelled the caffeinated beverage or the former United Nations secretary-general. It uses a probabilistic algorithm with roots in work done at AT&T Bell Laboratories in the early 1990s. The probabilities are based on a ‘noisy channel’ model, a fundamental concept of information theory. The model envisions a message source — an idealized user with clear intentions — passing through a noisy channel that introduces typos by omitting letters, reversing letters or inserting letters.

‘We’re trying to find the most likely intended word, given the word that we see,’ Mr. Paskin says. ‘Coffee’ is a fairly common word, so with the vast corpus of text the algorithm can assign it a far higher probability than ‘Kofi.’ On the other hand, the data show that spelling ‘coffee’ with a K is a relatively low-probability error. The algorithm combines these probabilities. It also learns from experience and gathers further clues from the context.”

Tags: James Gleick, Mark Paskin