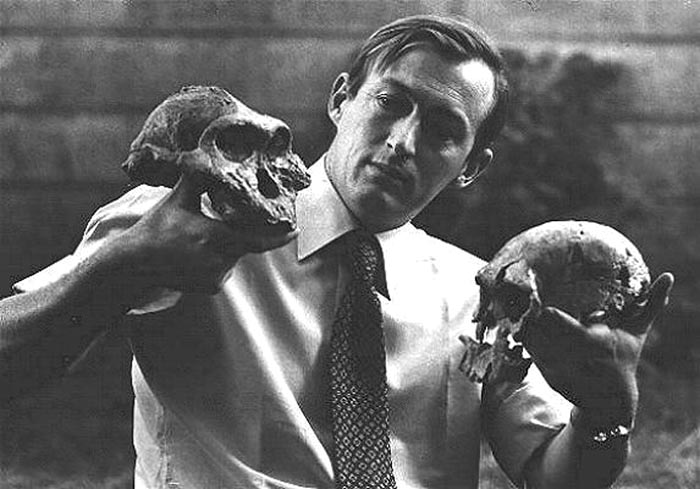

From “The Last Famine,” Paul Salopek’s sweeping Foreign Policy piece on hunger, a contemporary portrait of legendary paleoanthropologist Richard Leakey:

“The Turkana Basin is a freakishly beautiful place. A gargantuan wilderness of hot wind and thorn stubble, it covers all of northwestern Kenya and spills into neighboring Uganda, Ethiopia, and South Sudan. Black volcanoes knuckle up from its pale-ocher horizons. Lake Turkana — the largest alkaline lake in the world, 150 miles long — pools improbably in its arid heart. The lake is sometimes referred to, romantically, as the Jade Sea; from the air, its brackish waters appear a bad shade of green, like tarnished brass. Turkana, Pokot, Gabra, Daasanach, and other cattle nomads eke out a marginal existence around its shores. The basin’s dry sediments, which form part of the Great Rift Valley, hold a dazzling array of hominid remains. Because of this, the Turkana badlands are considered one of the cradles of our species.

Richard and Meave Leakey, the scions of the eminent Kenyan fossil-hunting family, have been probing deep history here for 45 years. Their oldest discovery, a pre-human skull, about 4 million years old, was found on a 1994 expedition led by Meave. An earlier dig headed by Richard uncovered a fabulous, nearly intact skeleton of Homo ergaster, dating back 1.6 million years, dubbed the Turkana Boy. Both Leakeys told me the modern landscape had changed nearly beyond recognition since their excavations began in the 1960s. The influx of food aid and better medical services had more than tripled the human population and stripped the region of most of its wild meat, wiping out the local buffalo, giraffe, and zebra. Domestic livestock — exploding and then crashing with successive droughts — had scalped the savannas’ fragile grasses. While driving one day near his headquarters, the Turkana Basin Institute, Richard pointed at a dusty cargo truck, its bed piled high with illegally cut wood. ‘Charcoal for the Somali refugee camps,” he said with a puckish smile. ‘The U.N. pays for it.’

Leakey is not only a celebrity thinker. He is also an incorrigible provocateur and a man of big and restless ambitions. Bored with the squabbles of academic research (‘I could never go back to measuring one tooth against another’), he abandoned the summit of paleoanthropology in the late 1980s to assume the directorship of Kenya’s enfeebled wildlife service, where he became a hero to conservationists by ordering elephant poachers shot on sight. A few years later, he helped organize Kenya’s first serious opposition party, and those activities invited years of police harassment. (A 1993 plane crash, which Leakey blames on sabotage, resulted in the loss of both his legs below the knee; he now gets around — driving Land Rovers, piloting planes — on artificial feet.) At one point, I asked him about heavy bandages on his head and hands at a recent lecture at New York’s Museum of Natural History. He had been suffering from skin cancers, he explained, that metastasized from old police-baton injuries. Leakey tends to view humankind through a very long lens, and pessimistically.”

••••••••••

Two Richards, Leakey and Dawkins:

Tags: Meave Leakey, Paul Salopek', Richard Leakey