I’m really bad at remembering faces but really good at reading them in the moment, which can be both advantageous and disconcerting. I don’t know that I’m happier for realizing that people are sometimes saying one thing while feeling another. I’m surprised when other people don’t seem to recognize the subtext contained in expressions and body language. Or perhaps they do and they’re just ignoring it. At any rate, it’s like having two very different conversations at the same time with a person, which is odd. From “The Naked Face,” Malcolm Gladwell’s excellent 2002 New Yorker article on the topic:

“All of us, a thousand times a day, read faces. When someone says ‘I love you,’ we look into that person’s eyes to judge his or her sincerity. When we meet someone new, we often pick up on subtle signals, so that, even though he or she may have talked in a normal and friendly manner, afterward we say, ‘I don’t think he liked me,’ or ‘I don’t think she’s very happy.’ We easily parse complex distinctions in facial expression. If you saw me grinning, for example, with my eyes twinkling, you’d say I was amused. But that’s not the only way we interpret a smile. If you saw me nod and smile exaggeratedly, with the corners of my lips tightened, you would take it that I had been teased and was responding sarcastically. If I made eye contact with someone, gave a small smile and then looked down and averted my gaze, you would think I was flirting. If I followed a remark with an abrupt smile and then nodded, or tilted my head sideways, you might conclude that I had just said something a little harsh, and wanted to take the edge off it. You wouldn’t need to hear anything I was saying in order to reach these conclusions. The face is such an extraordinarily efficient instrument of communication that there must be rules that govern the way we interpret facial expressions. But what are those rules? And are they the same for everyone?

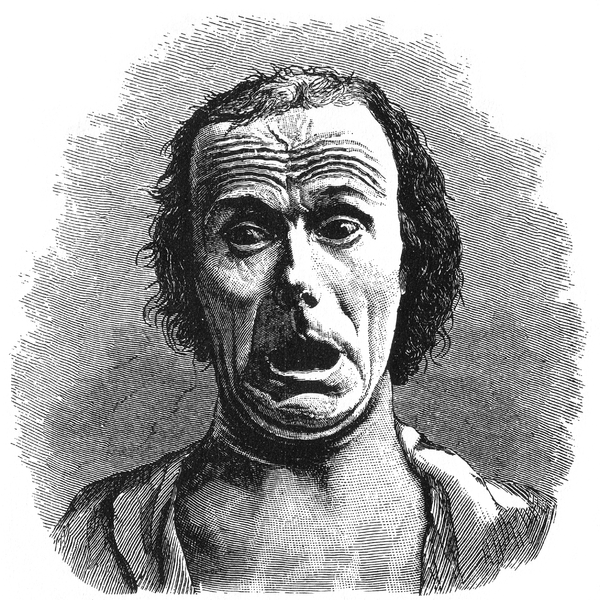

In the nineteen-sixties, a young San Francisco psychologist named Paul Ekman began to study facial expression, and he discovered that no one knew the answers to those questions. Ekman went to see Margaret Mead, climbing the stairs to her tower office at the American Museum of Natural History. He had an idea. What if he travelled around the world to find out whether people from different cultures agreed on the meaning of different facial expressions? Mead, he recalls, ‘looked at me as if I were crazy.’ Like most social scientists of her day, she believed that expression was culturally determined– that we simply used our faces according to a set of learned social conventions. Charles Darwin had discussed the face in his later writings; in his 1872 book, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, he argued that all mammals show emotion reliably in their faces. But in the nineteen-sixties academic psychologists were more interested in motivation and cognition than in emotion or its expression. Ekman was undaunted; he began travelling to places like Japan, Brazil, and Argentina, carrying photographs of men and women making a variety of distinctive faces. Everywhere he went, people agreed on what those expressions meant. But what if people in the developed world had all picked up the same cultural rules from watching the same movies and television shows? So Ekman set out again, this time making his way through the jungles of Papua New Guinea, to the most remote villages, and he found that the tribesmen there had no problem interpreting the expressions, either. This may not sound like much of a breakthrough. But in the scientific climate of the time it was a revelation. Ekman had established that expressions were the universal products of evolution. There were fundamental lessons to be learned from the face, if you knew where to look.” (Thanks TETW.)

Tags: Malcolm Gladwell