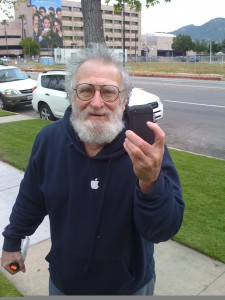

An original Blue Box at the Computer History Museum. Al Gilbertson invented the first such box, which gave callers the same control over the phone system as an operator. (Image by RaD man.)

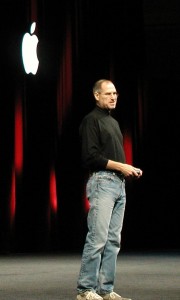

Before the World Wide Web allowed most of the planet to be readily connected, people were already using whatever techological gadget they had at hand to try to reach out-of-the-way places and obscure information. Phone phreaks were pre-computer revolution hackers who figured out ways to place free phone calls and learn the finer points about the phone company’s computer system. For phreaks (including the pre-Apple Steves, Jobs and Wozniak), this hacking was a training ground for future endeavors in the computer industry.

The phone company was not amused, however, so these phreaks hid behind aliases like “Captain Crunch” and “Legion of Doom.” It was a subculture that few knew about until 1971, when Ron Rosenbaum’s Esquire article, “Secrets of the Little Blue Box,” profiled hacker Al Gilbertson. An excerpt:

“There is an underground telephone network in this country. Gilbertson discovered it the very day news of his activities hit the papers. That evening his phone began ringing. Phone phreaks from Seattle, from Florida, from New York, from San Jose, and from Los Angeles began calling him and telling him about the phone-phreak network. He’d get a call from a phone phreak who’d say nothing but, ‘Hang up and call this number.’

When he dialed the number he’d find himself tied into a conference of a dozen phone phreaks arranged through a quirky switching station in British Columbia. They identified themselves as phone phreaks, they demonstrated their homemade blue boxes which they called ‘M-F-ers’ (for ‘multi-frequency,’ among other things) for him, they talked shop about phone-phreak devices. They let him in on their secrets on the theory that if the phone company was after him he must be trustworthy. And, Gilbertson recalls, they stunned him with their technical sophistication.

I ask him how to get in touch with the phone-phreak network. He digs around through a file of old schematics and comes up with about a dozen numbers in three widely separated area codes.

‘Those are the centers,’ he tells me. Alongside some of the numbers he writes in first names or nicknames: names like Captain Crunch, Dr. No, Frank Carson (also a code word for a free call), Marty Freeman (code word for M-F device), Peter Perpendicular Pimple, Alefnull, and The Cheshire Cat. He makes checks alongside the names of those among these top twelve who are blind. There are five checks.

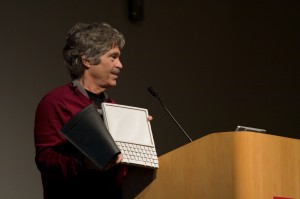

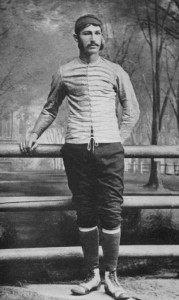

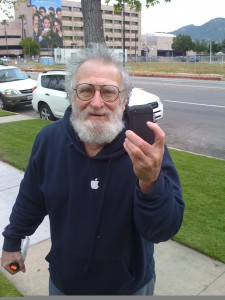

John T. Draper, the computer legend also known as "Captain Crunch." (Image by Aaron Getting.)

I ask him who this Captain Crunch person is.

‘Oh. The Captain. He’s probably the most legendary phone phreak. He calls himself Captain Crunch after the notorious Cap’n Crunch 2600 whistle.’ (Several years ago, Gilbertson explains, the makers of Cap’n Crunch breakfast cereal offered a toy-whistle prize in every box as a treat for the Cap’n Crunch set. Somehow a phone phreak discovered that the toy whistle just happened to produce a perfect 2600-cycle tone. When the man who calls himself Captain Crunch was transferred overseas to England with his Air Force unit, he would receive scores of calls from his friends and ‘mute’ them — make them free of charge to them — by blowing his Cap’n Crunch whistle into his end.)

‘Captain Crunch is one of the older phone phreaks,’ Gilbertson tells me. ‘He’s an engineer who once got in a little trouble for fooling around with the phone, but he can’t stop. Well, this guy drives across country in a Volkswagen van with an entire switchboard and a computerized super-sophisticated M-F-er in the back. He’ll pull up to a phone booth on a lonely highway somewhere, snake a cable out of his bus, hook it onto the phone and sit for hours, days sometimes, sending calls zipping back and forth across the country, all over the world….’

Back at my motel, I dialed the number he gave me for ‘Captain Crunch’ and asked for G—- T—–, his real name, or at least the name he uses when he’s not dashing into a phone booth beeping out M-F tones faster than a speeding bullet, and zipping phantomlike through the phone company’s long-distance lines.

When G—- T—– answered the phone and I told him I was preparing a story for Esquire about phone phreaks, he became very indignant.

‘I don’t do that. I don’t do that anymore at all. And if I do it, I do it for one reason and one reason only. I’m learning about a system. The phone company is a System. A computer is a System. Do you understand? If I do what I do, it is only to explore a System. Computers. Systems. That’s my bag. The phone company is nothing but a computer.'”