In Spin in 1988. Norman Mailer published ‘Understanding Mike Tyson,’ a piece of reportage about the last heavyweight that mattered, in those days when he was still ascendant in the ring, still the “Baddest Man on the Planet,” before things turned just plain bad. As is the case with a boxing card itself, the article first introduces all of the preliminary figures, making you wait for the person you came to see. The opening:

As an arena for boxing, the Convention Hall at Atlantic City is not one of the happier architectural palaces of the world. It drops the kind of pall on an audience that would come from witnessing a cock-fight in a bank. Lyndon Johnson was nominated there in 1964 with two identical sixty-foot close-up photographs of himself on either side of the podium. The Hall looked on that occasion like the coronation chamber for a dictator. Now, on the night of June 27, 1988, thousands of seats were laid on the great flat floor, and people in the seventeenth row ringside were paying $1,500 a ticket to see the Tyson-Spinks Heavyweight Championship. Since the gala glitz of the Trump Plaza was but a connecting corridor away from Convention Hall, and the Trump Plaza was architecturally close to its purpose, possessing a retina-red decor that inspired you to sport and gamble, the shock in moving from gaming tables to the fight was as palpable as sex after midnight is distinguishable from the gray dawn.

The fight also took forever to start. Celebrities were introduced for fifteen minutes and the successful gamblers who had given back some of their winnings for a last minute pair of tickets could now find a little consolation for the bad ringside seats. (Catching a bout from the seventeenth row is equal to watching a couple make love in a room on the other side of the street.) To be able to boo or cheer, however for Sean Penn and Madonna, Jackie Mason, Warren Beatty, Jack Nicholson, Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson, Marvin Hagler, George Steinbrenner (booed), Dexter Manley, Matthew Broderick, Carl Weathers, Burt Young, Judd Nelson, Chuck Norris, Oprah Winfrey, Don Johnson, Tom Brokaw, Don King, and Jesse Jackson, all in person, would revive the ego when telling about it to the folks back home.

At the press ringside, where you see the fight a lot better, the rumor was that Donald Trump had planned to invite Frank Sinatra to sit next to him but was worried that the ring floor might be pitched too high for Frank and other guests in the front row. So, the ring was lowered. Sinatra, working at rival Bally’s, declined the invitation. It was not appropriate to be seated next to the competition. The principle remained intact, however. Trump understood the psychology of success. It was more important that his front row contingent have a good view than that the suckers in the seventeenth pew complain because the ring had been pitched in a hollow.

Just before the fight began, Trump came into the ring with Muhammad Ali. Ali now moved with the deliberate awesome calm of a blind man, sobering all who stared upon him. He looked like the Shade of the boxing world. “I, who gave you great pleasures for years, now ask you to witness the costs of your pleasures,” he could as well have said. Then Trump standing beside him, was able to hear over the PA system, “New Jersey thanks you, Donald Trump.”

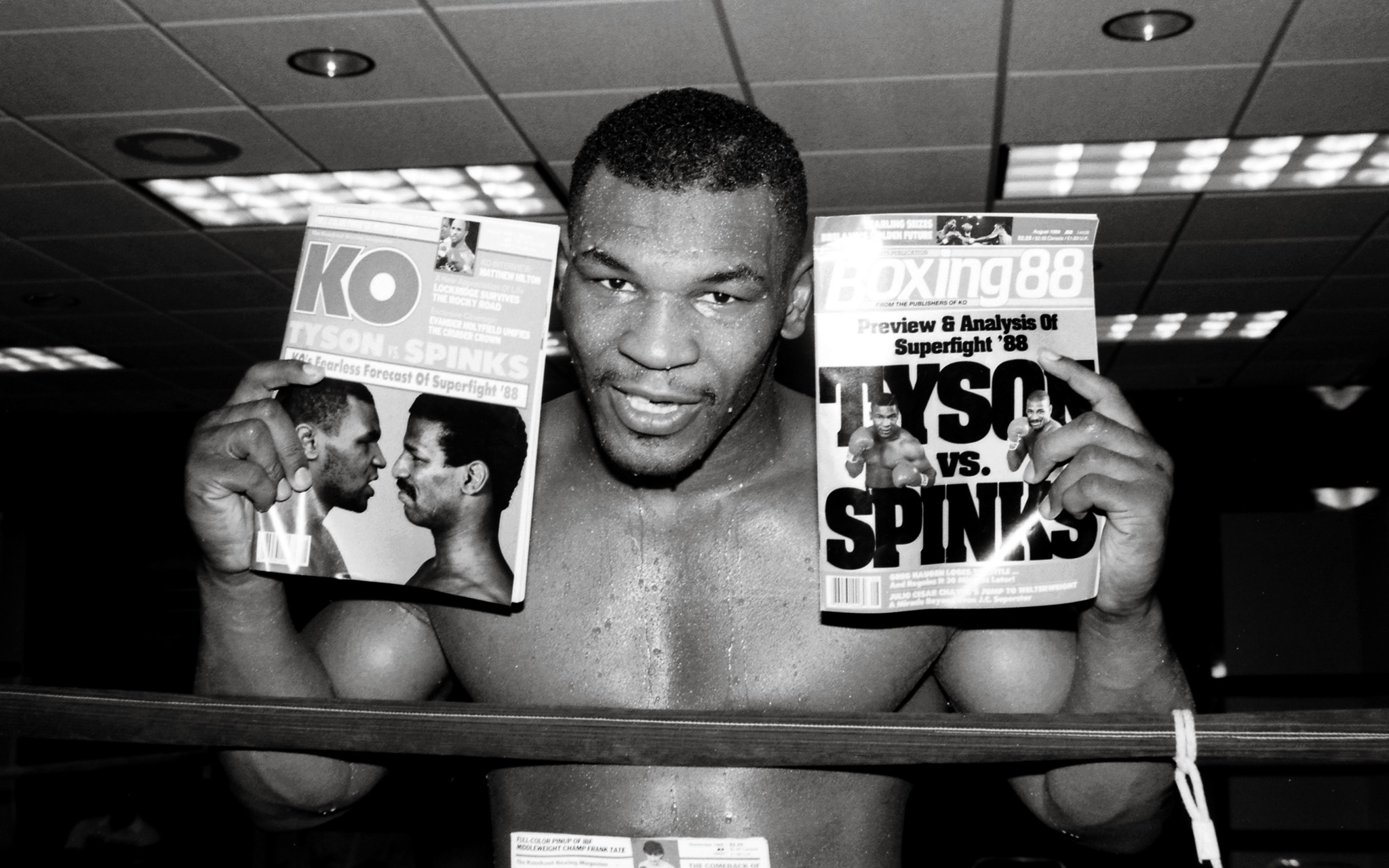

Spinks came into the ring wearing white trunks. He was a much-respected fighter. He has won thirty-two fights and lost none. He had been light-heavyweight champion and had moved up in weight to fight Larry Holmes, taking the heavyweight championship from Holmes by decision and keeping it in the return bout. He had knocked out Gerry Cooney in five rounds. He was an artfully awkward fighter who tried to never do the same thing twice, and he had been the underdog in many of his undefeated fights. He possessed a little of Ali’s magic–he found unorthodox ways to win. People who loved the gallant, the sly, and the innovative, liked Spinks. He invariably did a little better than expected. Tonight, however, he did not look happy. He was smiling too much. In fact, Spinks seemed distracted and relaxed at once. One had not seen that kind of separation from oneself since sitting next to Sonny Liston in a poker game the night before Liston’s second fight with Ali in Lewiston, Maine. Liston had been the relaxed man in the room. He had giggled equally whether he won or lost. The stakes were nickels and dimes, but Liston took great pleasure in peeking at his hole cards before each round of betting. It was easy to mistake such relaxation for confidence, yet the following night Liston was knocked out in one round by a punch that some are still insisting they never saw. It had not been relaxation that was witnessed at the poker game, but resignation.

So the sight of Spinks increased the pall. Spinks was giving a dry-mouthed smile. His nervousness was evident; worse, it was deep. Boxers can come into the ring keen with fear, or rendered sluggish by it, and Spinks did not look keen. It can well be an unendurable load to know for a hundred nights that one is going to face Mike Tyson at the end of them, Tyson with his thirty-four victories and no defeats, his power, his speed, his ongoing implacable offensive force.

Tyson, however, looked drawn. Not afraid, not worried, but used-up in one small part of himself, as if a problem still existed that he had not been able to solve. His expression suggested how hard it was to hold off murderous impulses for a long time. He was waiting for the bell.•