No too many paleontologists make the pages of People magazine, but the late Stephen Jay Gould was a serious academic who crossed over into the mainstream. The Queens-born Harvard professor was a lightning rod for others who disagreed with his theories, but Gould was someone who continually questioned himself, often revising beliefs from early essays in subsequent ones. An excerpt from Michelle Green’s 1986 People profile:

“It is an inviting, vaguely antic enclave that suggests a 19th-century natural history museum turned into a bookish boys’ club. Faded lettering on the drab green walls announces ‘Synopsis of the Animal Kingdom’ and ‘Sponges and Protozoa,’ and in the room’s cluttered depths are a wealth of musty treasures: tall glass cases filled with drawers of trilobites, a towering painting of a tyrannosaurus, hundreds of leather-bound volumes and boxes of snail shells. A worn rattan chair has been pulled up to a worktable that holds fossils, microscopes and a supply of Pepperidge Farm cookies.

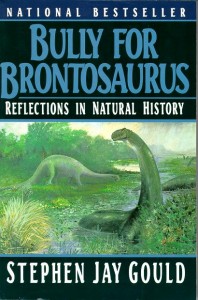

Stephen Jay Gould—evolutionary biologist, prolific writer and die-hard Yankees fan—has worked in this office at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology for 17 years, and many of his books have been spawned here: Ever Since Darwin, The Panda’s Thumb, Hen’s Teeth and Horse’s Toes and now The Flamingo’s Smile (Norton, $17.95). When he arrived with his freshly minted Ph.D. from Columbia, the rumpled, kinetic Gould was an exceptionally promising paleontologist; in the years since, he has become a popular symbol of erudition and scholarship. At 44, he recently completed the final year of a MacArthur Foundation grant that has paid him $38,400 a year since 1981. He was the recipient of an American Book Award in 1981, a National Magazine Award in 1980 and once made the cover of Newsweek. He has done battle with creationists, testified before congressional committees concerning nuclear winter and lectured in South Africa on the history of racism. Students fight to get into his classroom, and assorted crazies send tirades addressed to Mr. Illustrious Historical Professor Jay Gould, University of Harvard.

On this stone-gray afternoon, the illustrious historical professor is finding all the attention a bit of a problem. His secretary is putting through calls approximately every two minutes, and Gould—an ebullient man with a near-perpetual smile—is simultaneously trying to discuss his life’s work and fend off a flood of petitioners. On his desk is the latest batch of correspondence, including a letter from a man who suggests a connection between AIDS and aspirin, and a plea from the husband of a woman who is addicted to Gould’s columns in Discover:: Will the author please send birthday greetings to the following address? This nets the correspondent a hastily scrawled turndown: ‘I am not public property, but a man!'”