John DeLorean remade the automotive industry, remade himself and eventually made a mess.

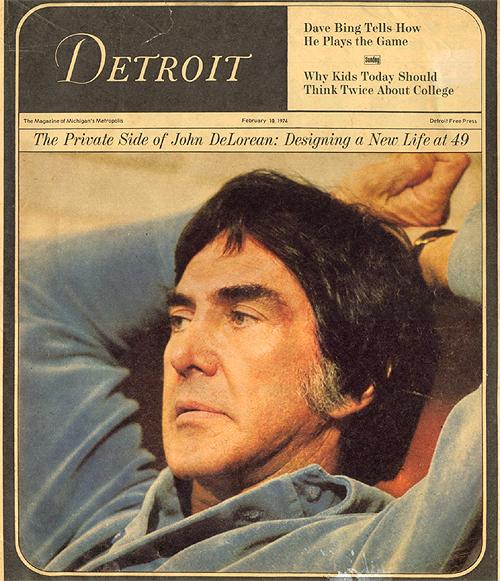

The opening of “The Private Side of John DeLorean: A New life at 49,” a great 1974 Detroit magazine cover story written by Paul Hendrickson, which profiled the legendary automaker after he exited the corporate car culture to blaze his own trail but before his head-on collision with hubris:

It begins like a parable. A skinny kid from inner-city Detroit grows up in the ’40s playing Slide the Rock and sandlot baseball and sometimes the clarinet. His father is a set-up man at the Ford foundry. His mother, separated from her husband, lives in California.

The boy is crazy for cars, dreaming of them every day as he rides a trolley down Woodward on his way to Cass Tech. Growing like a weed, he enters Lawrence Institute of Technology, graduates in engineering and, in 1948, begins a 25-year career in the automobile industry. Along the way, he picks up two master’s degrees, a wife from northern Michigan and 200 patents, including the recessed windshield wiper, the hidden radio antenna and the overhead-cam engine.

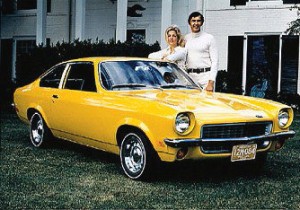

His rise at General Motors in meteoric. In 1965, at age 40, he is made general manager at Pontaic and a vice president. At 44, he becomes the youngest man ever to direct Chevrolet. Three years later, in October, 1972, he is named head of all GM’s car and truck production. His salary, including bonuses, is said to be $650,000. He is most everybody’s odds-on favorite to one day become president.

But here, the story takes a swerve. For by 1972, John Zachary DeLorean was a different breed of cat than the naive, callow youth who entered the business with the conviction that making cars was his calling to help Americans preserve their fifth freedom, mobility. For one thing, he had drastically changed his lifestyle.

He had taken to turtlenecks and tie-dyed blue jeans by then. His weight was down from 235 to just over 170. His hair was long and sculptured and dyed coal-black. There were well-founded stories that he had undergone a face lift. His three-to-four-pack-a-day cigarette habit was gone, as were the suits that came off the rack, as was the first wife. He had also married and divorced actress-model Kelly Harmon, 24 years his junior, and had popped up around the country in the company of Ursula Andress, Nancy Sinatra and Candice Bergen. When in Detroit, he had been known to roar around in such non-GM models as a Lamborghini and a $19,000 Maserati Ghibli. On occasion, he shocked everybody at the office cold by coming to work in a pickup.

He was playing golf with Arnold Palmer and Gary Player, riding motorcycles in the Mojave Desert, chasing girls with one-time auto racer Roger Penske and collecting real estate as if America were his Monopoly board.

In short as Time magazine put it, by 1972 John DeLorean was standing out from his colleagues at GM like a Corvette Stingray or a showroom full of trucks.

But more than any of that, DeLorean by then was just plain disenchanted with his job. He had said at a press conference two years earlier that he did not intend to spend the rest of his life at GM; few believed him.•

John DeLorean’s combustible 1980s, in four videos.

Mesmerizing 17-minute DeLorean DMC-12 prospectus film that was shown to dealers and investors ahead of the automobile reaching the market in 1981.

From Pennebaker and Hegedus in 1981: “John Zachary DeLorean doesn’t smile very much.”

A 1983 California ad offering DeLoreans at the closeout price of $18,895. “This may be your last chance to live the dream.”

In 1988, his dreams dashed and reputation destroyed, DeLorean was living in Manhattan, now a born-again Christian, still believing he would get another chance. He granted a rare interview to a local TV station from his old stomping grounds in Detroit.

Tags: John DeLorean, Paul Hendrickson