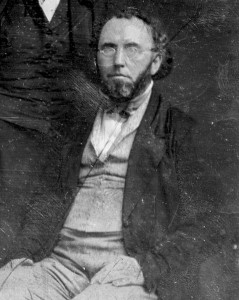

Transcendentalist and literary editor George Ripley founded Brook Farm in Massachusetts. It was no Utopia.

From “Utopia & Dystopia,” Paul La Farge’s excellent 2010 BookForum essay about the horrifying nature of Utopian settlements (both fictional and actual), from Sir Thomas More forward:

“The history of real-world utopias bears his observation out. One of America’s best-known utopian experiments was performed at Brook Farm, in Massachusetts, where members of the Transcendentalist intelligentsia, among them Nathaniel Hawthorne, tried their hands at a communal life inspired by the writings of Fourier. The Brook Farmers lacked the funds to live well and the skills to live cheaply; they went into debt and argued about doctrine, and when their half-built phalanstery burned down in the spring of 1846, the community went into a decline from which it did not recover. The most enduring monument to Brook Farm is Hawthorne’s novel The Blithedale Romance (1852), which, far from praising the experiment, describes a group of city folk going obstinately to seed, their minds numbed by work, their hearts ablaze with impractical and ultimately tragic romantic combinations.

The Brook Farmers’ misfortune was small compared with that of the Icarians. It’s hard to see how Cabet’s novel could have inspired anyone to serious activity; nevertheless, in 1848, sixty-nine French people, dressed in black velour uniforms, set sail from Le Havre for Texas, where they were to establish a colony. They settled on the Red River, where they caught yellow fever; by the time Cabet arrived with the second group of colonists, a year later, their society had fallen apart. The Icarians relocated to Nauvoo, Illinois, whence the Mormons had just been chased: Presumably the real estate came cheap. Fifteen hundred Icarians gathered in Nauvoo, but they accomplished little, aside from printing a tract in which Cabet described how nice a society he could make if someone were to give him half a million dollars. The group split; Cabet and his loyalists departed for Saint Louis, where Cabet died a few days later. The remainder of the group bought land in Iowa, which so depleted their resources that they lived for years in mud houses and walked around in wooden shoes. Their splendor was all in their ‘somewhat elaborate’ constitution, drafted by Cabet, ‘which lays down with great care the equality and brotherhood of mankind, and the duty of holding all things in common; abolishes servitude and service (or servants); commands marriage, under penalties; provides for education; and requires that the majority shall rule.’

Eventually the Icarians built a schoolhouse and a dining hall, but their society failed to enchant the outside world. Of the sixty-five members who moved to Iowa in 1856, thirty were gone by 1860; the last Icarians disbanded in 1898. Most utopian societies met similar ends: The Harmonists of Pennsylvania lost their money in a lawsuit; the Separatists of Zoar dwindled to nothing. The Oneida Perfectionists, notorious in their day for practicing institutionalized polyamory, fell into scandal and squabbling, then reformed themselves into a silverware company that left its members to form their own matched sets.” (Thanks Essayist.)