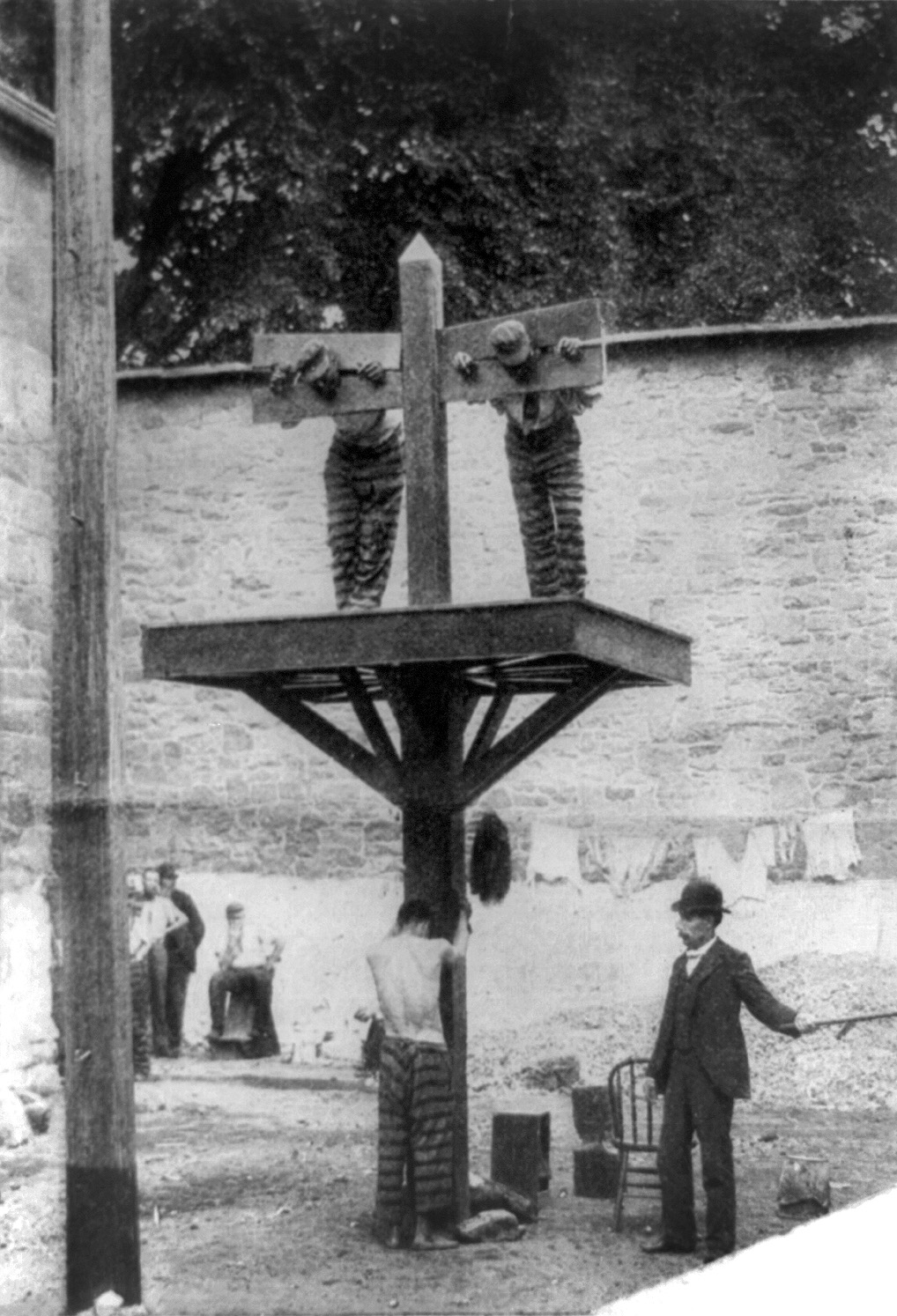

"The instance is rare where a man voluntarily selects a penal institution for his home and refuses to leave it, even when threatened with physical ejection."

If you were looking for someone to help you plan a prison break at the Raymond Street Jail in Brooklyn during the latter part of the nineteenth century, James Davis was definitely not your man. Even though he never committed a crime, Davis checked into the jail one day as if it were a hotel and never checked out–even when ordered to. Because he was a useful guy and caused no grief, a succession of sheriffs allowed the unusual living arrangement to continue. The October 25 1896 Brooklyn Daily Eagle profiled the curious “convict.” An excerpt:

“Raymond Street Jail has been prolific in characters, most of them bad. Some of them almost beyond redemption. They have nearly all of them pined for freedom, but all of them have been compelled to wait till the law had been satisfied. There have been a few cases in prisons and penitentiaries to the state where long term convicts have been disinclined to leave the bars after having been pardoned, or at the expiration of their sentences. The instance is rare where a man voluntarily selects a penal institution for his home and refuses to leave it, even when threatened with physical ejection. Such a man, however, may be found in the institution over which Sheriff Buttling presides. His name is James Davis. The denizens of the place refer to him and have for many years as Jimmie. Sometimes they call him Jimmie the Paup. Paup with them is a contraction for pauper. They have named him as they have named others with sobriquets that are more laughable to their cult than they are elegant, accurate or appropriate.

Davis has been a voluntary prisoner in the Raymond Street Jail for twenty-one years. He is an undersized individual of perhaps 55, and wears a little black mustache. His strong characteristic is his silence on all topics, except for prize fighting. On the latter three-fourths of his conversation is devoted to eulogy of Peter Maher, whom he thinks the greatest disciple of fisticuffs the world has ever seen. Comparatively little is known of the early life of Davis, and in fact, comparatively little effort has been taken by the individual himself to communicate any knowledge to those among whom he lives. He is wary of all strangers, and runs away generally when they move forward to investigate him. His value to every sheriff for the past twenty years in this county has been great. Sheriff Buttling, in speaking of him, to an Eagle reporter, said:

‘I can say many good things about our voluntary prisoner. He proves a very valuable man at times. He seems to have the ability to make the inmates do the work assigned to them, and is quick to report any violation of the jail discipline. Why he remains at the jail when he might be doing better for himself is something I do not understand.’

The books of the jail do not show that Davis has been guilty of any offense. He just strolled in many years ago and was allowed to occupy a cell in consideration of doing chores around the place. He spoke to few, went his own way and was in no way objectionable to any officials. From one cell, Davis gradually became the tenant of two. In one cell, Davis has a rather extensive collection of portraits of prize fighters. They are all cheap prints, many of them cut from advertisements, of gaudy colors and poor execution. Davis’ cell is always clean.

When Warden Shanley assumed charge of the jail Davis’ case puzzled him a good deal. He didn’t care to have the fellow around the place, because at that time he did not appreciate his value. He thought he would tell Davis to go and did so, but the voluntary prisoner would not budge. The warden quickly learned enough about him to see the propriety of retaining him. The fellow is certainly content. Sheriff Buttling says he believes that Davis would prefer his cell to a room in a mansion.”