"Just like the old man in that book by Heinz von Lichberg" would have been the worst Police lyric ever.

The opening of Jonathan Lethem’s excellent long-form 2007 Harper’s essay, “The Ecstasy of Influence: A Plagiarism,” which looks at the way artists borrow, whether through cryptomnesia, repurposing or stealing:

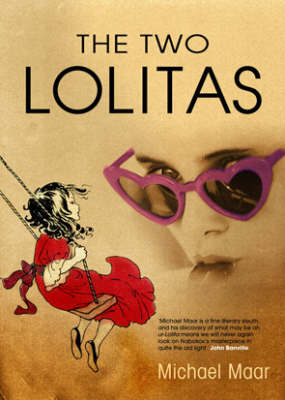

“Consider this tale: a cultivated man of middle age looks back on the story of an amour fou, one beginning when, traveling abroad, he takes a room as a lodger. The moment he sees the daughter of the house, he is lost. She is a preteen, whose charms instantly enslave him. Heedless of her age, he becomes intimate with her. In the end she dies, and the narrator—marked by her forever—remains alone. The name of the girl supplies the title of the story: Lolita.

The author of the story I’ve described, Heinz von Lichberg, published his tale of Lolita in 1916, forty years before Vladimir Nabokov’s novel. Lichberg later became a prominent journalist in the Nazi era, and his youthful works faded from view. Did Nabokov, who remained in Berlin until 1937, adopt Lichberg’s tale consciously? Or did the earlier tale exist for Nabokov as a hidden, unacknowledged memory? The history of literature is not without examples of this phenomenon, called cryptomnesia. Another hypothesis is that Nabokov, knowing Lichberg’s tale perfectly well, had set himself to that art of quotation that Thomas Mann, himself a master of it, called ‘higher cribbing.’ Literature has always been a crucible in which familiar themes are continually recast. Little of what we admire in Nabokov’s Lolita is to be found in its predecessor; the former is in no way deducible from the latter. Still: did Nabokov consciously borrow and quote?” (Thanks Essayist.)

••••••••••

Vladimir Nabokov discusses Lolita in the 1950s: