Orson Welles’ 1974 cine-essay about the art of the hoax is sensational in both senses of the word, zestfully beginning as an examination of one fraud and stumbling ass-backwards into an even bigger scam. As if the engaging, globe-trotting Hungarian art forger Elmyr de Hory wasn’t a fascinating-enough figure for this uncommon documentary, his biographer, Clifford Irving, who was interviewed extensively by Welles for the film, proved to be a better one.

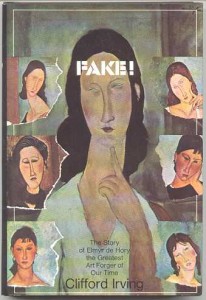

Failed fiction writer Irving seemed to hit his stride in 1969 when he published Fake!, a true-crime account about de Hory, a perpetually struggling artist who decided to exploit his incredible facility for mimicking the painting styles of masters. He’d whip up a Matisse or Picasso and feign being a former Hungarian aristocrat who was selling family treasures because he was cash poor. Plenty of art dealers knew it was a ruse, but since de Hory’s work was so convincing, they tacitly went along with the con to get rich. De Hory’s forgeries purportedly hang in museums all over the world, and his remarkable tale made the book a best-seller and gave Welles his initial subject.

But then a better subject emerged.

While the film was being made, Irving’s own more spectacular fraud began to be exposed. His new book, an “authorized” biography about reclusive tycoon Howard Hughes, whom he had never met or spoken to, was proven to be a phony. The fallout gave Welles an even richer palette to work with, and his story gleefully bounces from faker to faker, examining how they did what they did and how they came undone. The resulting work is a playful, freewheeling meditation, a Godardian Welles film, that examines a pair of hoaxers from every angle with eagerness and a respect that’s far more than grudging.

While the film was being made, Irving’s own more spectacular fraud began to be exposed. His new book, an “authorized” biography about reclusive tycoon Howard Hughes, whom he had never met or spoken to, was proven to be a phony. The fallout gave Welles an even richer palette to work with, and his story gleefully bounces from faker to faker, examining how they did what they did and how they came undone. The resulting work is a playful, freewheeling meditation, a Godardian Welles film, that examines a pair of hoaxers from every angle with eagerness and a respect that’s far more than grudging.

The third hoaxer in the film is, of course, Welles himself, a self-professed “charlatan,” whose 1938 War of the Worlds radio broadcast about Martians invading Earth caused widespread panic in a country that was still very naive about media manipulation. Welles admired scammers because he knew that legitimate artists con their audiences into believing an illusion and that hoaxers are just their purer brethren and their creations valuable. As de Hory says of his uncanny canvases, “If you hang them in a museum long enough, they become real.”

____________________________________

Welles made a nine-minute trailer that used material not in the final film. Click on the “Watch on YouTube” link to view the short.

Tags: Clifford Irving, Elmyr de Hory, Howard Hughes, Orson Welles