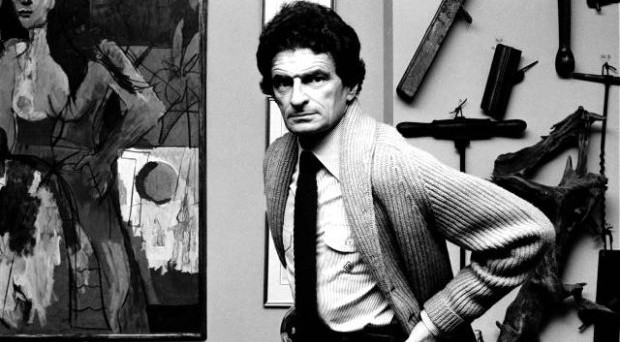

Like a lot of people who move to New York to reinvent themselves, Jerzy Kosinksi was a tangle of fact and fiction that couldn’t easily be unknotted. He was lauded and reviled, labeled as brilliant and a plagiarist, called fascinating and a fraud. The truth, as usual, probably lies somewhere in between. Kosinski was a regular on talk shows, at book parties and at Plato’s Retreat. He acted in Reds and posed for magazine covers. But he was too haunted to be a bon vivant, and in 1991, the author committed suicide.

Kosinski did an interview with The Paris Review in 1972. He opined about what he felt was the ever-dwindling importance of written and verbal language. He was very concerned by how much people liked to watch. Since his death, the Internet has supplanted TV as the premium medium, allowing people to write and publish more words than ever before, though that hasn’t really halted our drift deeper into pictures.

An excerpt:

Question:

Since you often teach English, what is your feeling about the future of the written word?

Jerzy Kosinski:

I think its place has always been at the edge of popular culture. Indeed, it is the proper place for it. Reading novels–serious novels, anyhow–is an experience limited to a very small percentage of the so-called enlightened public. Increasingly, it’s going to be a pursuit for those who seek unusual experiences, moral fetishists perhaps, people of heightened imagination, the troubled pursuers of the enlightened self.

Question:

Why such a limited audience?

Jerzy Kosinski:

Today, people are absorbed in the most common denominator, the visual. It requires no education to watch TV. It knows no age limit. Your infant child can watch the same program you do. Witness its role in the homes of the old and incurably sick. Television is everywhere. It has the immediacy which the evocative medium of language doesn’t. Language requires some inner triggering; television doesn’t. The image is ultimately accessible, i.e., extremely attractive. And, I think, ultimately deadly, because it tuns the viewer into a bystander.

Of course, that’s a situation we have always dreamt of . . . the ultimate hope of religion was that it would release us from trauma. Television actually does so. It “proves” that you can always be an observer of the tragedies of others. The fact that one day you will die in front of the live show is irrelevant—you are reminded about it no more than you are reminded about real weather existing outside the TV weather program. You’re not told to open your window and take a look; television will never say that. It says, instead, “The weather today is . . .” and so forth. The weatherman never says, “If you don’t believe me, go find out.”

From way back, our major development as a race of frightened beings has been toward how to avoid facing the discomfort of our existence, primarily the possibility of an accident, immediate death, ugliness, and the ultimate departure. In terms of all this, television is a very pleasing medium: one is always the observer. The life of discomfort is always accorded to others, and even this is disqualified, since one program immediately disqualifies the preceding one. Literature does not have this ability to soothe. You have to evoke, and by evoking, you yourself have to provide your own inner setting. When you read about a man who dies, part of you dies with him because you have to recreate his dying inside your head.

Question:

That doesn’t happen with the visual?

Jerzy Kosinski:

No, because he dies on the screen in front of you, and at any time you can turn it off or select another program. The evocative power is torpedoed by the fact that this is another man; your eye somehow perceives him as a visual object. Thus, of course, television is my ultimate enemy and it will push reading matter—including The Paris Review—to the extreme margin of human experience.•