A few months ago, I excerpted a Wired article in which Steven Levy revisited some subjects profiled in his great 1984 book, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. That book looked at the pioneers from the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s who built the foundation of today’s interconnected technology. I’m rereading Hackers now, so I thought I’d provide a passage. This sequence is about the moment when computers passed over from institutions into the hands of Berkeley hackers. Eventually, some of the folks who cut their teeth on this XDS-940 Bay Area behemoth would help personal computing take quantum leaps forward, but initially the work was as unglamorous as it was idealistic and exciting. An excerpt:

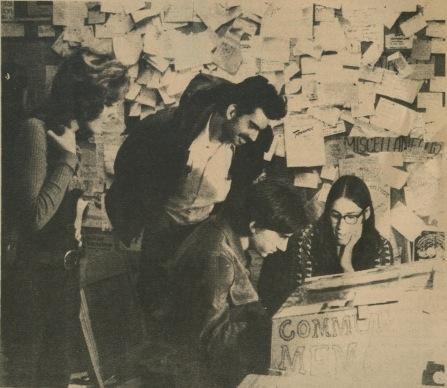

“The first public terminal of the Community Memory project was an ugly machine in a cluttered foyer on the second floor of a beat-up building in the spaciest town in the United States of America: Berkeley, California. It was inevitable that computers would come to ‘the people’ in Berkeley. Everything else did, from gourmet food to local government. And if, in August 1973, computers were generally regarded as inhuman, unyielding, warmongering and nonorganic, the imposition of a terminal connected to one of those Orwellian monsters in a normally good-vibes zone like the foyer outside of Leopold’s Records on Durant Avenue was not necessarily a threat to anyone else’s well-being. It was yet another kind of flow to go with.

Outrageous, in a sense. Sort of a squashed piano, the height of a Fender Rhodes, with a typewriter keyboard instead of a musical one. The computer was protected by a cardboard box casing, with a plate of glass set in its front. To touch the keys, you had to stick your hands through little holes, as if you were offering yourself for imprisonment in an electronic stockade. But the people standing by the terminal were familiar Berkeley types, with long stringy hair, jeans, and a demented gleam in their eyes that you would mistake for a drug reaction if you did not know them well. Those who did know them well realized that the group was high on technology. They were getting off like they had never gotten off before, dealing the hacker dream as if it were the most potent strain of sinsemilla in the Bay Area.

The name of the group was Community Memory, and according to a handout they distributed, the terminal was ‘a communication system which allows people to make contact with each other on the basis of mutually expressed interests, without having to cede judgements to third parties.’ The idea was to speed the flow of information in a decentralized, non-bureaucratic system. An idea born from computers, an idea executable only by computers, in this case a time-shared XDS-940 mainframe machine in the basement of a warehouse in San Francisco. By opening a hands-on computer facility to let people reach each other, a living metaphor would be created, a testament to the way computer technology could be used as guerrilla warfare for people against bureaucracies.”

Tags: Steven Levy