I found an interesting factoid in Edward L. Glaeser’s City Journal article about the role of entrepreneurship in New York City’s past, present and future. It seems that in the 19th-century, cargo ships didn’t set sail on any particular day but only when they had a full hull. That meant cargo could sit in a port for weeks, as the ship waited for more customers. Then someone had the idea that vessels should depart at scheduled times. Seems obvious, but it wasn’t. The person behind this innovation was Jeremiah Thompson, a Quaker businessman and a member of the free-slave group, the New York Manumission Society. An excerpt:

“Entrepreneurs have played a key role in every stage of New York’s development. During the early nineteenth century, when waterways were the lifelines of commerce, New York owed its expanding sea trade partly to natural advantages: a safe, centrally located harbor and a deep river that cut far into the American hinterland. But those advantages became important because of the vision and energy of entrepreneurs like Jeremiah Thompson, the gambling Quaker. Thompson immigrated to New York at 17 to work in the American branch of his family’s wool business. By the 1820s, he had established himself as America’s largest importer of English clothing, its largest exporter of raw cotton, and its third-largest issuer of bills of exchange.

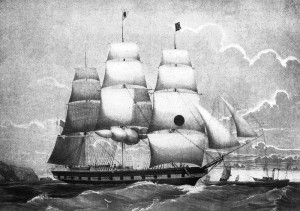

As a global trader, Thompson was acutely aware of the shortcomings of the transatlantic ships of the time, which would stay in port until their hulls were filled with goods. (Imagine showing up at LaGuardia and having to sit around until the airline sold enough tickets to fill the entire flight to Frankfurt.) Thompson saw an opening and created the Black Ball packet line, whose ships set sail on a scheduled day every month, no matter how light their cargoes were. His innovation was a gamble, since sometimes his ships sailed with relatively empty hulls, which meant less income from the merchants who bought the space. But a virtuous circle developed: fixed schedules attracted more cargo, and more cargo made ships sailing on fixed schedules more profitable. Once Thompson was turning a profit, other packet lines, like the Yellow Ball and Swallowtail lines, entered the market. An 1827 letter to the New England Palladium described the significance of Thompson’s invention: ‘I consider Commerce by lines of ships, on fixed days, an invention of the age nearly as important as Steam Navigation and in its results as beneficial to New York, which has chiefly adopted it, as the Grand [Erie] Canal.'”