I briefly got my hands on a hardback copy of Allen C. Thomas’ 1900 primary-school book, An Elementary History of the United States, which covers the years from pre-Columbus times to the eve of the 20th-century. Thomas was a history professor at Haverford College. This book was owned in 1919 by a child named Bruce Alexander, who drew a red mustache on the illustration of George Washington.

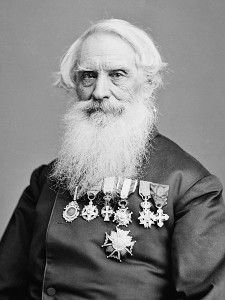

One of the later chapters, entitled “Inventions,” recalls how Samuel Morse helped create the telegraph during the 1830s and 1840s. An excerpt:

“Morse at once saw that messages could be sent at great distances if wires were properly arranged. His invention was very simple, and there was very little about it that was original. After it was described, it seemed strange that scientific men had not thought of his method before.

Morse, like almost all inventors, had much to contend with. He was poor, and had it not been for a young man named Alfred Vail, who persuaded his father to lend Morse some money, it is quite possible that there would have been failure after all.

Vail was an excellent mechanic, and helped very much in the construction of the instruments. He also secured for Morse a patent for the invention.

In order to bring his invention before the public, Morse asked Congress, at Washington, to give thirty thousand dollars, to be used in constructing a telegraph line between Baltimore and Washington, a distance of forty miles. Some members of Congress made all manner of sport of Morse’s project. One member proposed that the money should be spent in making a railroad to the moon.

There seemed little prospect that the bill granting the money would be passed. The story is told that Morse, weary and heart-sick, sat hour after hour in the gallery of the Senate Chamber, waiting for the bill to come up before Congress adjourned. When evening came and there seemed no chance for its passage, he went to his hotel utterly discouraged, and prepared to leave for New York early the next day, as his money was exhausted.

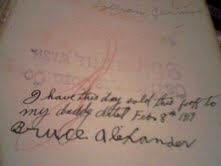

Written on inside cover: "I have this day sold this book to my daddy dated Feb. 8th 1919. Bruce Alexander."

The next morning, while he was at breakfast, a young lady came in and said, ‘I congratulate you.’ ‘Upon what?’ said Morse, who was feeling rather blue. ‘On the passage of your bill.’ ‘Impossible.’ ‘No,’ she said, ‘It was passed five minutes before the adjournment.’ ‘Well,’ said Morse, ‘you shall send the first message over the lines.’

The line was constructed with the money thus secured. When all was ready Morse kept his promise, and Miss Annie G. Ellsworth sent, at the suggestion of her mother, the words, ‘What hath God wrought!’ That was on May 25, 1844. It was not many years before there were telegraphs over all civilized lands.”

Tags: Alfred Vail, Allen C. Thomas, Annie G. Ellsworth, Bruce Alexander, George Washington, Samuel Morse