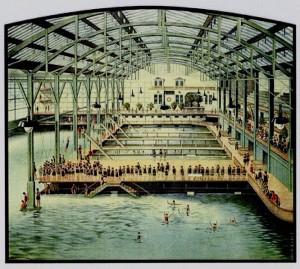

"Some of them keep away from baths now because they never had one and are afraid to begin." (Image by Kristen Holden.)

People in Brooklyn in the late-nineteenth century were apparently a bunch of slobs who lacked indoor plumbing and needed a good scrubbing. They stunk to the high heavens, and everyone was close to fainting from the nasty smell. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle offered a solution for the cleansing of filthy citizens in the most demeaning, insulting terms in its August 13, 1897 edition: Build some public baths, so these miserable scumbags could be less stanky. An excerpt:

“An enthusiastic support of Mr. Henriques’ device to build public baths under the bridge is assured from a majority of the people. It cannot be denied that baths of some sort are sadly needed in quarters of the city. Ocular and olfactory evidence of that fact is offered only too freely. We have a few floating baths, but they are ridiculously inadequate to the demands upon them. On any warm day you shall see the string of youngsters extended far up the pier, and many are their dodges to escape the vigilance of the police in order to get in ahead of their turn or even commit the offense of going in twice.

Bathing is to be encouraged in the young. If they persist in it the custom will adhere to them through life. It is desirable that it should adhere to everybody. If not, other things will. It is not the individual alone who profits by the practice of bathing, but the community. If we could feel assured that every citizen in Brooklyn took a bath daily we could laugh at cholera and bubonic plague. Even diphtheria and allied diseases would be lessened, not because clean people are always exempt from them, but because a habit for personal cleanliness begets a habit for cleanliness and order in one’s surroundings and the clean man will desire to live in a clean house.

Near the bridge are unclean persons who live in houses that menace the health of the whole river front. More over, apart from its most obvious virtue bathing has sanitary influence as a stimulant and a sedative. People are awakened by a bath at noon, and a dip on a hot night often enables them to sleep. The swimming and other exercise induced by a plunge in a large pool are likewise beneficial. But why restrict these baths to the edges of the town? They should be for the whole people. Water is a public property, even if we are a little short of it at this moment. In any case, there is the Atlantic Ocean to draw from, for bathing purposes, too, if we are very short.

Rome had baths so fine and solid in their architectural setting that their ruins are still more substantial than half of the buildings in Brooklyn, and so general and constant were they in use that it was possible to put them at the service of the multitude for a penny or two, while the plunge baths were free to all comers. The regular bath was similar to what we know as the Turkish bath and included sweating, shampooing, swimming and drying. What a different people those of the east side of New York might be if they were persuaded into establishments like that, at least once a week!

And in time they could be. Some of them keep away from baths now because they never had one and are afraid to begin. This is serious, indeed, too serious. If they could be persuaded to try one many of them would like it. They would induce their friends and command their offspring to try them. Then they would begin to clean up their homes a little and desist from throwing trash about their streets. In time they would become as Americans and would exhibit that virtue which is next to godliness.”