On a trip to Seattle some years back, I picked up this fun book, at the Elliott Bay Book Company, by the late area historian Murray Morgan. It tells the tale of some of the most colorful characters in the city’s history, including John Considine, who risked life and limb to bring vaudeville and other more raffish entertainments (gambling, prostitution, etc.) to Seattle during the boom time of the Klondike Gold Rush.

And I’m not kidding when I say he risked his life. Considine had a long-running feud with Police Chief William L. Meredith. After Considine exposed some corruption on the Chief’s part and got him fired, things turned really ugly. In 1901, Meredith first slandered Considine by claiming he impregnated a 17-year-old contortionist and paid for her abortion, and then he shot Considine at point-blank range. Considine was wounded, but not fatally. Meredith wasn’t so lucky when Considine returned fire. Since the deposed lawman had started the shootout, Considine was acquitted by the jury.

Considine eventually cleaned up his ways and brought the first superior movie theater to Seattle and later became involved in the budding motion picture business in Los Angeles. But before all of that, there were the rowdy days of the illicit People’s Theater. Due to anti-vice efforts and economic problems, Considine briefly lost control of the theater. In 1897, he schemed to get it back. An excerpt from Morgan’s book:

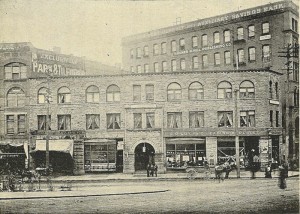

“One the evening of the last Thursday in December 1897, a large man wearing a brown derby, a gray raincape, and white gloves, and leading a brindle bulldog on a silver chain, strolled through the rain down Second Avenue South, gravely declining the invitation of streetwalkers and, on occasion, raising his cane in salute to a friend. He paused for a moment at the corner of Second Avenue and Washington to watch the men going down the steps into the People’s Theater. Even on a miserable midwinter night the place was drawing well; young sports out on the town, loggers in for the holidays, businessmen, and, most of all, lonesome Easterners waiting for ships bound for Alaska.

The big man watched thoughtfully, then went to the head of the steps. He frowned at the black-and-gold sign that read, ‘People’s Theater. Moses Goldsmith, Prop.’ Nailed to the wall was a blackboard on which had been written in crayon: ‘See Lady Osmena change clothes in total darkness in a lion cage.’

He went down the steps, paid fifty cents for a seat near the stage, ordered a glass of ‘water plain, unadorned water,’ from an amazed waitress, and turned his attention to the crowd. The place was full. The bar, which stretched along one wall, was crowded; three bartenders were kept busy. Nearly every table was occupied. Women with painted cheeks and skirts nearly up to their knees roamed the room, smiling at the patrons; from time to time the girls went to the stage and sang a loud song or danced an awkward dance. From the curtained box seats in the low balcony came the laughter and shouts and giggles and, most important, a steady ringing of bells as the box-hustlers summoned waiters with drinks.

The place was a gold mine, John Considine decided, a real gold mine. He’d have to get it back.”