There’s something wrong with people who play pranks. It seems like fractured sexual energy fashioned into a whoopee cushion. But as any longtime reader of this site knows, I’m fascinated by the legendary hoaxster Alan Abel, a blend of Lenny Bruce and Allen Funt whose deadpan presentation bedeviled broadcasters when TV was the primary American media. Abel’s gift is being able to divine our desires and fears before we can name them, and then reflect them through ridiculous stunts that are obviously fake yet fool the masses because of the collective holes in our souls. More than anyone else, he’s the cultural antecedent to Sacha Baron Cohen.

In a smart Priceonomics post, Zachary Crockett profiles man who is–and isn’t–serious. The opening (followed by video of a few Abel hoaxes):

On May 27, 1959, a mysterious, bespectacled man in a suit appeared on The Today Show. After briskly introducing himself, he turned to the camera and told America of his mission: to “clothe naked animals for the sake of decency.”

The man went by the name of G. Clifford Prout, and he claimed to be the president of an organization called The Society for Indecency to Naked Animals (S.I.N.A.). Naked animals, he harped, were “destroying the moral integrity of our great nation” — and the only solution was to cover them up with pants and dresses.

Prout’s impassioned speech did not fall on deaf ears: within days, S.I.N.A. attracted more than 50,000 members. For the next four years, the organization and its leader topped news headlines, made the rounds on talk shows, and spurred heated debates among pundits.

But S.I.N.A. was not real: it was the invention of Alan Abel, history’s greatest media hoaxster.

Over his 60-year “career” as a professional hoaxster, Abel orchestrated more than 30 high-profile stunts — from faking his own death to convincing the press he had the world’s smallest penis. He tricked top New York Times reporters, trolled Walter Cronkite, and weaseled his way into tens of thousands of print publications and talk shows.

His hoaxes attempted to make some kind of political commentary — on censorship, backwards moral standards, or the vapidity of daytime television. But often, they would be taken literally, riling up supporters and revealing ugly truths about America. He preyed on the media’s hunger for juicy stories, and ultimately revealed its gullibility.•

________________________

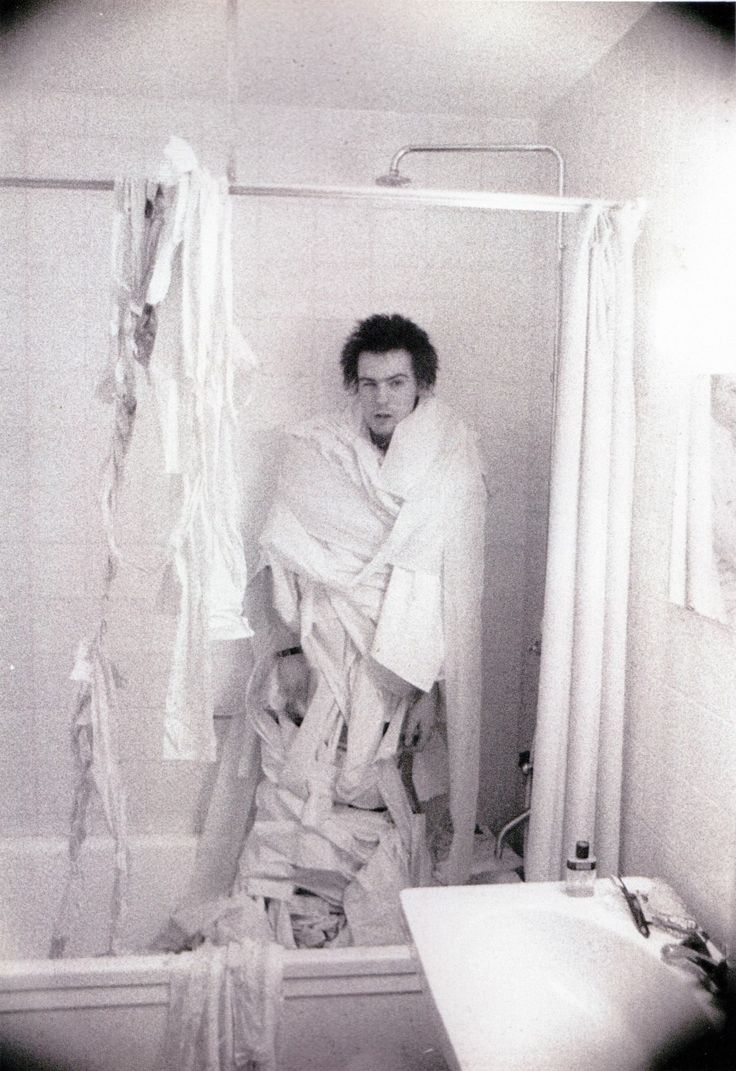

A funny and prescient piece of performance art in which Abel responded to an ad placed by a 1999 HBO show seeking men willing to discuss their genitalia. Abel presented himself as a 57-year-old musician with a micro-penis. The hoaxer was ridiculing the early days of Reality TV, in which soft-headed pseudo-documentaries were offered to the public by cynical producers who didn’t exactly worry about veracity. Things have gotten only dicier since, as much of our culture, including news, makes no attempt at objective truth, instead encouraging individuals to create the reality that comforts or flatters them. Language is NSFW, unless you work in a gloryhole.

________________________

In this ridiculous interview from basic cable decades ago, Abel satirized our wish for fame, youth and immortality, marrying the emerging celebrity culture to new scientific possibilities. He pretended that he’d created a sperm bank in which only stars like John Wayne and Johnny Carson were allowed to make deposits. And he was going to cryogenically freeze a young woman and tour her body across America. Everyone would be a star and live forever.

________________________

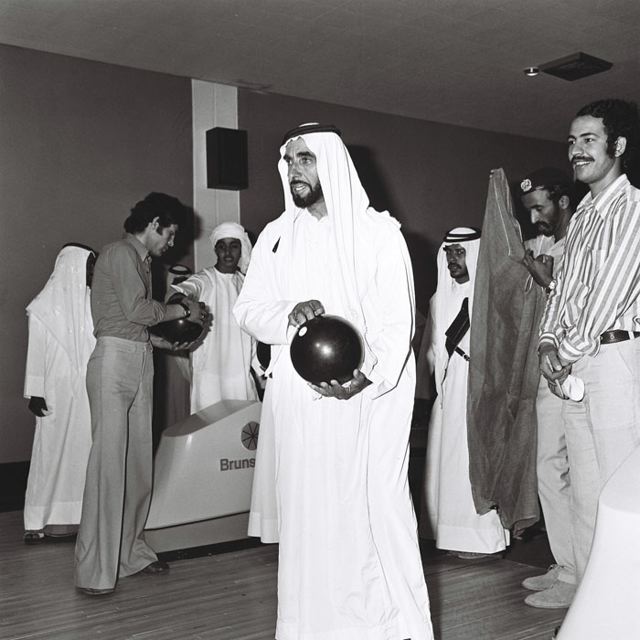

In a 1970s scam, the wiseacre posed as a tennis-loving sheik, playing off America’s fear and loathing of newly minted OPEC millionaires, at a time when our post-WWII lustre had faded. Abel created the character of Prince Emir Assad, who competed in a Pro-Am tourney.

________________________

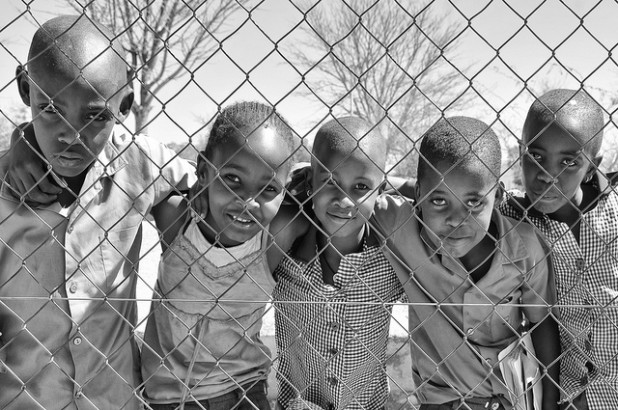

Abel pulled a prank during the economic downturn of the early 1990s in which he pretended to be a financially desperate man willing to sell his kidneys and lungs. The ruse was eagerly devoured by news media because it toyed furiously with the fear of falling being experienced by a shrinking American middle class, which was under extreme pressure from a dwindling manufacturing base, anti-unionists and technology-driven downsizing. Things have clearly grown even worse.