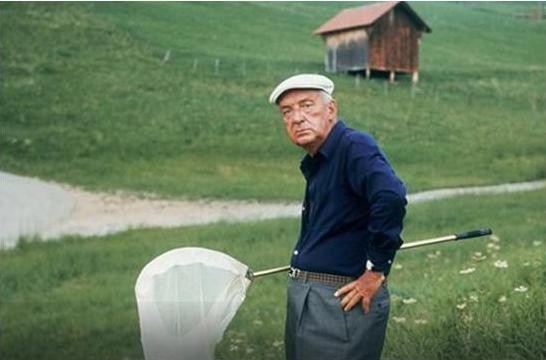

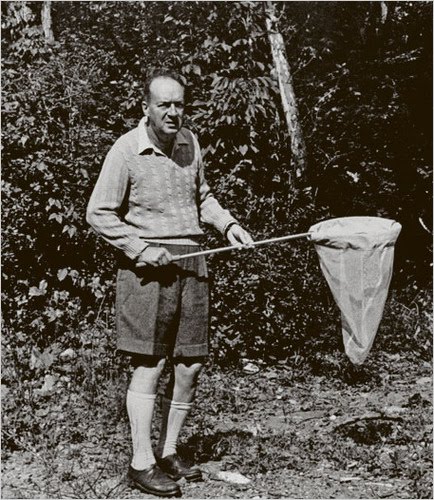

How exactly did Vladimir Nabokov do it, writing the Great American novel, though he wasn’t American? I’ve argued in the past that Lolita, his story of monstrous obsession, was probably aided by an immigrant’s eye, his observations about his adopted country not dulled by total absorption in its culture. However, Nabokov did have to be somewhat familiar with the nation in order to so brilliantly dissect it. He had to take it in before he could size it up. The author collected his reconnaissance in a typically U.S. way: the road trip.

The opening of “On the Trail of Nabokov in the American West,” Landon Y. Jones’ New York Times article:

For the last 15 years my wife, Sarah, and I have driven every summer with our golden retriever from New Jersey to the Northern Rockies. I used to say that I felt like Humbert Humbert, the notoriously unreliable narrator of Lolita, who made a similar trip, but instead of traveling with a precocious preteen girl, I was traveling with a wife and a dewy-eyed dog.

But then I learned that Vladimir Nabokov himself had done the same thing. Nabokov wrote his disturbingly compelling classic, Lolita, over the course of five breathless years, from 1948 to 1953, filling 5-by-7 cards with notes he took riding shotgun while his designated driver, his wife, Véra, drove their black Oldsmobile from Ithaca, N.Y., to Arizona, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming and Montana.

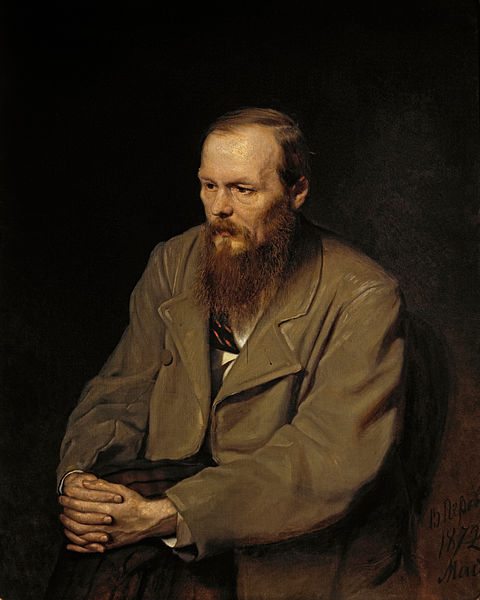

In other words, at the height of the Cold War, an expatriate Russian novelist with the resonant name of Vladimir was roaming through the reddest of red states, researching a book about a jaded aristocrat’s sexual obsession with “nymphets” (a coinage the book put in the Oxford English Dictionary). The wonder is that Nabokov survived at all.

Today we revere Lolita for Nabokov’s bold, multilayered subject matter and his dazzling and allusive prose. But Nabokov’s most enduring contribution may be his portrait of the brash, kitschy, postwar America he observed on his cross-country journeys. Nabokov never learned to drive, and so he estimated that between 1949 and 1959 Véra drove him 150,000 miles — almost all of them on the two-lane blue highways that preceded the interstates.

Measured by the sheer number of miles covered, Nabokov is the most American of authors. He saw more of the United States than did Fitzgerald, Kerouac or Steinbeck, and what he saw was back-roads America: personal, intimate, ticky-tack and yet undeniably authentic. It took a Russian-born writer to awaken us to what Mark Twain knew: America is not a place; it is a road.•