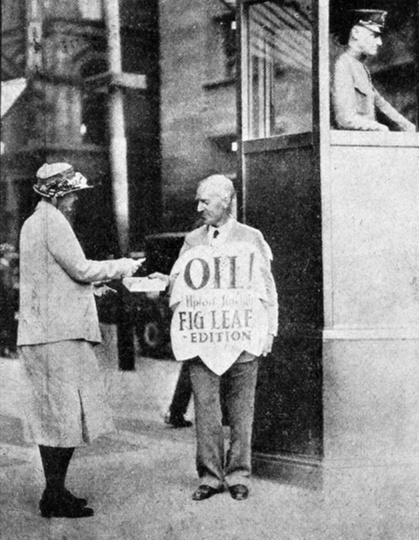

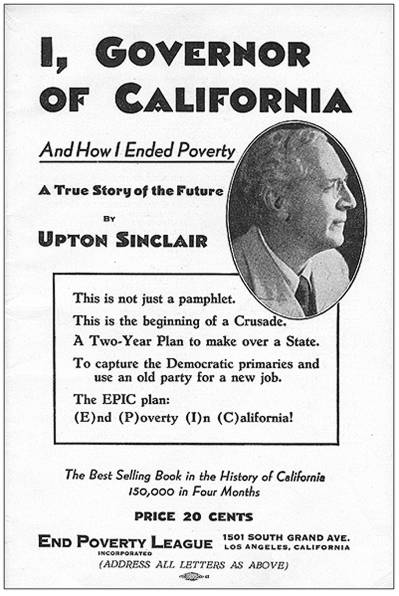

Just read Chip Brown’s New York Times Magazine piece about the boomtown that North Dakota has become thanks to its massive oil reserves in this post-peak age, which reminded of this classic photograph of Upton Sinclair selling bowdlerized copies (the so-called fig-leaf edition) of his novel Oil! on a street in Boston, where the book was banned. (This novel is the basis for Paul Thomas Anderson’s great film There Will Be Blood.) The Beantown controversy helped boost Oil! to bestseller status. Sinclair, a radical firebrand, was no stranger to such public contretemps, whether running for the office of governor or hatching plans for a commune near the Palisades in New Jersey. On the latter topic, here’s a passage from a 1906 New York Times article about the formation that year of Sinclair’s techno-Socialist collective, Helicon Home Colony, which burned to the ground the year after its establishment:

“Not less than 300 persons answered Upton Sinclair’s call for a preliminary meeting at the Berkeley Lyceum last night of all those who are interested in a home colony to be organized for the purpose of applying machinery to domestic processes, and incidentally to solve the servant problem. The idea of the proposed colony is to syndicate the management of children and other home worries, such as laundering, gardening, and milking cows.

The response to Mr. Sinclair’s call gratified him immensely. When he went on the stage he was smiling almost ecstatically. The audience applauded him and then began to mop their faces, for the little Lyceum was almost filled, and some one had to shut the front doors.

The audience was made up almost equally of men and women. A large proportion seemed to be of foreign birth. Many of them were Socialists, judging from their manifestations of sympathy for Socialistic doctrines. The mentioning of two newspapers which disapprove of Socialism on their editorial pages was hissed. Mr. Sinclair himself said that he had thought of asking a Socialist to act as temporary Chairman, but that his man had thought that two Socialists on the stage at the same time would frighten the more conservative members.

The meeting lasted about two hours. Mr. Sinclair, at various times, had the floor about an hour and a half. Now and then the arguments caused a high pitch for excitement, and more than once four people were trying to talk at the same time. In the end always, however, what Mr. Sinclair suggested was accepted, including the appointment of committees and other preliminaries of organization.

For Mr. Sinclair is certain that his home colony is to come about. He said in his introductions that he had about a dozen people who had agreed to go in with him, whether anybody else did or not. But last night’s meeting indicated, in Mr. Sinclair’s opinion, that a home colony of at least 100 families could easily be organized.”