Tyler Cowen has made it difficult to take him seriously with his tepid performance during this great threat to America’s decency and democracy. He’s gone out of his way to make it seem his fellow Libertarian Peter Thiel is an innocent bystander who just hopes to do good work inside a somewhat dysfunctional Administration. What bullshit. Thiel was one of the driving forces of a deeply bigoted white nationalist campaign that used any and all means—including espionage, perhaps—to push an ignorant, mentally unfit incompetent and a raft of tiki-torchers into the White House. Pretending otherwise is intellectually dishonest. Thiel doesn’t move in the political circles he does by accident. That’s who he is.

It’s at least dawned on Cowen that bigotry, not economics, was the driving force in the U.S. election, a phenomena that has been witnessed in recent elections around the world. That’s not to say legitimate concerns about wealth inequality are absent from this new abnormal, but that the bigger issue is a sad tribal meme that’s gone viral all over the globe.

The opening of the Bloomberg View column “The New Populism Isn’t About Economics“:

Economic theories of populism are dead, we Americans just don’t know it yet. Over the past week, two countries have brought populists to power, but in both cases those places have been enjoying decent economic growth.

Andrej Babis’s party dominated the Czech national election Saturday, and he is almost certain to become the next prime minister. Babis has been described as “the anti-establishment businessman pledging to fight political corruption while facing fraud charges himself” — sound familiar? Yet in 2015, the Czech Republic had the European Union’s fastest growth rate at more than 4 percent; earlier this year, it was growing at 2.9 percent, with potential seen on the upside.

Last week’s negotiations in New Zealand brought Labour Party leader Jacinda Ardern to power, with populist firebrand Winston Peters in the coalition government. Ardern wants to cut immigration, possibly in half, and place much tighter restrictions on foreign investment. Although New Zealand’s economic growth has been slowing, it’s mostly been above 2 percent since the end of the financial crisis.

Among emerging economies, the Philippines moved from being an Asian growth laggard into some years of 8 percent growth. Voters responded by electing as president Rodrigo Duterte, one of the most aggressive and authoritarian populists around. In eastern Europe, Poland has been seeing average 4 percent growth for more than 25 years, yet the country has moved in a strongly nationalist direction, flirting with sanctions from the EU for limiting judicial independence. Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia and now the Czech Republic all are much wealthier than 20 years ago and mostly have been booming as of late. Yet to varying degrees they too have moved in nationalist, populist and possibly even anti-democratic directions.

Although these countries have rising inequality, their growth rates have elevated a wide swath of the citizenry, not just a few extremely wealthy people.

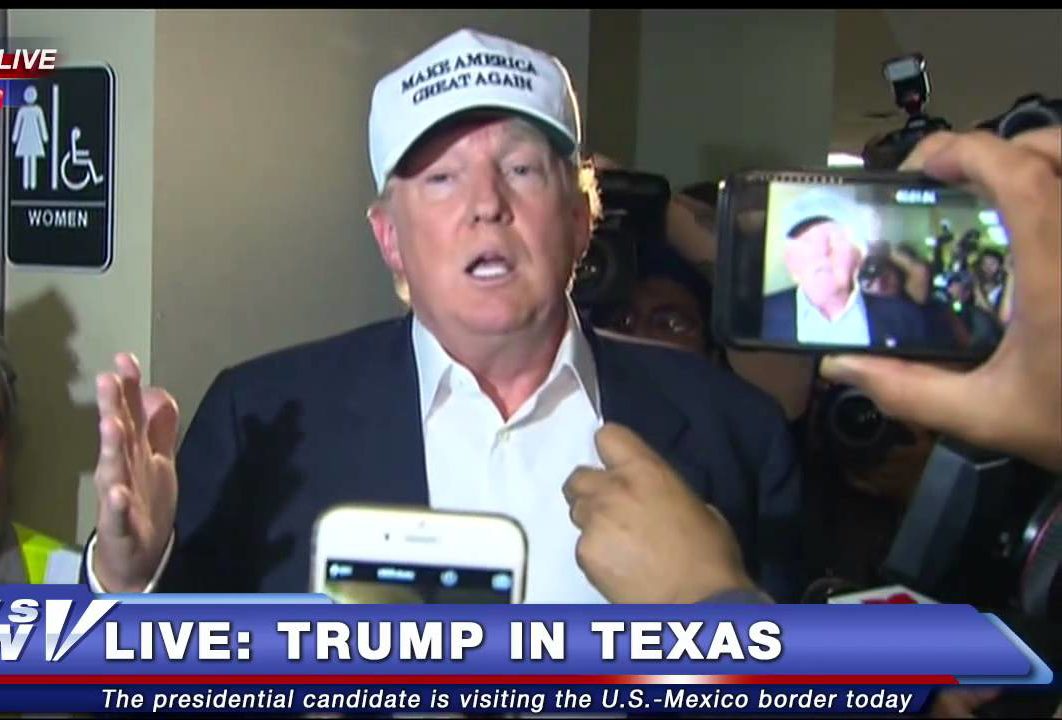

Even the U.S. fits this mold of prosperity and populism more than many people realize. For all the talk of stagnant wages, poll data indicated that Donald Trump’s supporters in the Republican primaries had a median income of about $72,000, which is hardly poverty. Wages and household median income have started to rise once again.

The trend continues outside the world’s democracies. …

It’s time to admit that the nationalist turn in global politics isn’t mainly about economics or economic failures.•