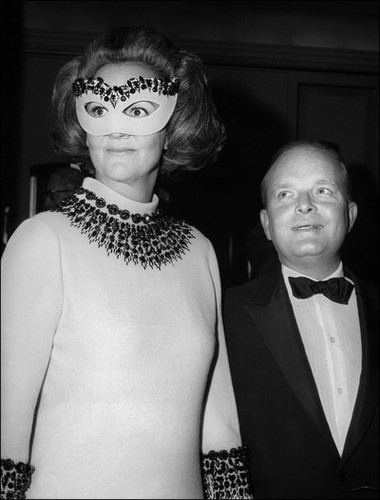

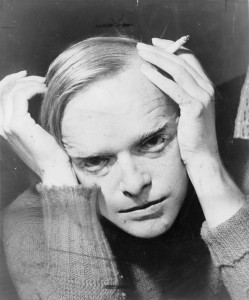

A passage from one of the most infamous TV interviews ever, Stanley Siegel questioning a seriously inebriated Truman Capote in 1978, a time before the commodification of dysfunction was prevalent.

You are currently browsing articles tagged Truman Capote.

Tags: Stanley Siegel, Truman Capote

The opening of Seth Abramovitch’s Hollywood Reporter article about that town’s strange obsession with the Blackwing 602, a pencil that went out of production in 1998 and whose supply continues to dwindle:

“In the spring of 1960, Vladimir Nabokov was living in a rented villa in Los Angeles’ Mandeville Canyon, hard at work adapting his novel Lolita into a screenplay for Stanley Kubrick. He wrote in four-hour stretches, planted in a lawn chair ‘among the roses and mockingbirds,’ he later wrote, ‘using lined index cards and a Blackwing pencil for rubbing out and writing anew the scenes I had imagined in the morning.’ With more than 1,000 cards to work with, the scribe found that his pencil arguably became his most trusted collaborator.

Nabokov isn’t alone in his devotion to the Blackwing 602, without question among the most fetishized writing instruments of all time. It counts among its cultish fan base some of the greatest creative geniuses of the 20th century, from John Steinbeck (‘I have found a new kind of pencil — the best I have ever had!’ he wrote) to Quincy Jones (the Thriller producer says he carries one under his sweater when making ‘continual fixes’ to his music) and Truman Capote (who stocked his nightstands with fresh boxes) to Stephen Sondheim, who has composed exclusively with Blackwings since the early 1960s.

The pencil even made its way onto television’s most object-obsessive series, AMC’s Mad Men, put there by TV director Tim Hunter, who says, ‘I just had always felt that these folks would be using Blackwings.’ Animators, including artists who drew such iconic characters as Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse, remain its most die-hard devotees — and earliest hoarders: The Blackwing 602 is becoming increasingly rare as it fast approaches its 80th birthday, with ostensibly only a few thousand in existence among the 13,000 that comprised its last lot in 1998, when the line was phased out.”

Tags: John Steinbeck, Quincy Jones, Seth Abramovitch, Stanley Kubrick, Stephen Sondheim, Truman Capote, Vladimir Nabokov

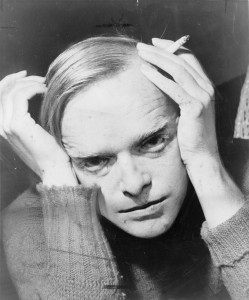

Part of an 1969 interview David Frost conducted with Truman Capote, who was already four years into a long decline, having published his masterpiece, In Cold Blood, in 1965, after a long struggle, with cycles of celebrity, scandal, addiction and rehab awaiting him. When I was a small child, I was taking a bus trip with my parents from the Port Authority, and we saw Capote seated on the benches, wearing a big straw hat, wasted out of his mind. He was trying to get a homeless woman to talk to him. She had no interest.

Tags: David Frost, Truman Capote

Truman Capote’s final, uncompleted novel, Answered Prayers, the one that was excerpted in Esquire in the 1970s and destroyed his social life, was never published in full. No one is totally sure where the hundreds of pages reside, but it’s believed they’re languishing in an unknown California bank security-deposit box, waiting to be found. At least that’s the theory put forth in Sam Kashner’s recent Vanity Fair piece, “Capote’s Swan Dive“:

“After Capote’s death, on August 25, 1984, just a month shy of his 60th birthday, Alan Schwartz (his lawyer and literary executor), Gerald Clarke (his friend and biographer), and Joe Fox (his Random House editor) searched for the manuscript of the unfinished novel. Random House wanted to recoup something of the advances it had paid Truman—even if that involved publishing an incomplete manuscript. (In 1966, Truman and Random House had signed a contract for Answered Prayers for an advance of $25,000, with a delivery date of January 1, 1968. Three years later, they renegotiated to a three-book contract for an advance of $750,000, with delivery by September 1973. The contract was amended three more times, with a final agreement of $1 million for delivery by March 1, 1981. That deadline passed like all the others with no manuscript being delivered.)

Following Capote’s death, Schwartz, Clarke, and Fox searched Truman’s apartment, on the 22nd floor of the U.N. Plaza, with its panoramic view of Manhattan and the United Nations. It had been bought by Truman in 1965 for $62,000 with his royalties from In Cold Blood. (A friend, the set designer Oliver Smith, noted that the U.N. Plaza building was ‘glamorous, the place to live in Manhattan’ in the 1960s.) The three men looked among the stacks of art and fashion books in Capote’s cluttered Victorian sitting room and pored over his bookshelf, which contained various translations and editions of his works. They poked among the Tiffany lamps, his collection of paperweights (including the white rose paperweight given to him by Colette in 1948), and the dying geraniums that lined one window (‘bachelor’s plants,’ as writer Edmund White described them). They looked through drawers and closets and desks, avoiding the three taxidermic snakes Truman kept in the apartment, one of them, a cobra, rearing to strike.

The men scoured the guest bedroom, at the end of the hallway—a tiny, peach-colored room with a daybed, a desk, a phone, and lavender taffeta curtains. Then they descended 15 floors to the former maid’s studio, where Truman had often written by hand on yellow legal pads.

‘We found nothing,’ Schwartz told Vanity Fair. Joanne Carson claims that Truman had confided to her that the manuscript was tucked away in a safe-deposit box in a bank in California—maybe Wells Fargo—and that he had handed her a key to it the morning before his death. But he declined to tell her which bank held the box. ‘The novel will be found when it wants to be found,’ he told her cryptically.”

Tags: Alan Schwartz, Joanne Carson, Joe Fox, Oliver Smith, Sam Kashner, Truman Capote

Gore Vidal regularly diminished other writers-often really talented ones–as a means of elevating himself. It’s an immature and cheap way of making yourself seem superior. (It’s the same thing that Chevy Chase, that miserable prick, does with fellow comedians). In a 2006 interview conducted by Jon Wiener that’s published at Los Angeles Review of Books, Vidal used this tactic on Truman Capote and Thomas Pynchon, two writers who were his betters and who turned out works that will outlast anything he did. Not even close. An excerpt:

“Jon Wiener:

One of the things they do at community colleges is teach writing. I think there are programs everywhere now. At my school, U.C. Irvine, we have an undergraduate major called ‘Literary Journalism.’ It started only a couple of years ago, but it already has over 200 majors, and if there are 200 at Irvine, there is a similar number at a hundred other schools. This means hundreds of thousands of students are studying to be writers. What do you make of this?

Gore Vidal:

We have Truman Capote to thank for that. As bad writers go, he took the cake. So bad was he, you know, he created a whole new art form: the nonfiction novel. He had never heard of a tautology, he had never heard of a contradiction. His social life was busy. To have classes in fiction — that really is hopeful, isn’t it. People can go to school and bring in physics. The genius of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow: he had to take all of his first year courses at, what was it, Cornell? One of his teachers was Nabokov. And everything he had in his first year’s physics went in to Gravity’s Rainbow. Whether it fit in or not, it just went in there. That’s one way of doing it.”

Tags: Gore Vidal, Jon Wiener, Thomas Pynchon', Truman Capote

William F. Buckley and the In Cold Blood author on capital punishment, in 1968.

Trailer for Into the Abyss, Werner Herzog’s new film about capital punishment:

Longform made an incredible find with “The Duke In His Domain,” a 1957 New Yorker profile of Marlon Brando by Truman Capote. The former was already an icon thanks to Streetcar, The Wild One and On the Waterfront; the latter was still roughly a decade from publishing his masterpiece, In Cold Blood. Capote traveled to the set of Sayonara in Tokyo to interview Brando, who was at the start of a long personal decline, still somewhat accessible but increasingly less so. An excerpt:

“The maid had reëntered the star’s room, and Murray, on his way out, almost tripped over the train of her kimono. She put down a bowl of ice and, with a glow, a giggle, an elation that made her little feet, hooflike in their split-toed white socks, lift and lower like a prancing pony’s, announced, ‘Appapie! Tonight on menu appapie.’

Brando groaned. ‘Apple pie. That’s all I need.’ He stretched out on the floor and unbuckled his belt, which dug too deeply into the swell of his stomach. ‘I’m supposed to be on a diet. But the only things I want to eat are apple pie and stuff like that.’ Six weeks earlier, in California, Logan had told him he must trim off ten pounds for his role in Sayonara, and before arriving in Kyoto he had managed to get rid of seven. Since reaching Japan, however, abetted not only by American-type apple pie but by the Japanese cuisine, with its delicious emphasis on the sweetened, the starchy, the fried, he’d regained, then doubled this poundage. Now, loosening his belt still more and thoughtfully massaging his midriff, he scanned the menu, which offered, in English, a wide choice of Western-style dishes, and, after reminding himself ‘I’ve got to lose weight,’ ordered soup, beefsteak with French-fried potatoes, three supplementary vegetables, a side dish of spaghetti, rolls and butter, a bottle of sake, salad, and cheese and crackers.

‘And appapie, Marron?’

He sighed. ‘With ice cream, honey.’

Though Brando is not a teetotaller, his appetite is more frugal when it comes to alcohol. While we were awaiting the dinner, which was to be served to us in the room, he supplied me with a large vodka on the rocks and poured himself the merest courtesy sip. Resuming his position on the floor, he lolled his head against a pillow, drooped his eyelids, then shut them. It was as though he’d dozed off into a disturbing dream; his eyelids twitched, and when he spoke, his voice—an unemotional voice, in a way cultivated and genteel, yet surprisingly adolescent, a voice with a probing, asking, boyish quality—seemed to come from sleepy distances.

‘The last eight, nine years of my life have been a mess,’ he said. ‘Maybe the last two have been a little better. Less rolling in the trough of the wave. Have you ever been analyzed? I was afraid of it at first. Afraid it might destroy the impulses that made me creative, an artist. A sensitive person receives fifty impressions where somebody else may only get seven. Sensitive people are so vulnerable; they’re so easily brutalized and hurt just because they are sensitive. The more sensitive you are, the more certain you are to be brutalized, develop scabs. Never evolve. Never allow yourself to feel anything, because you always feel too much. Analysis helps. It helped me. But still, the last eight, nine years I’ve been pretty mixed up, a mess pretty much.'”

••••••••••

Dick Cavett interviews a reluctant Brando in 1973. After the show, Brando took Cavett to dinner in Chinatown, and the actor famously punched paparazzo Ron Galella, breaking his jaw. The photographer sued and ultimately agreed to a $40,000 settlement.

Watch the rest of interview here.

Tags: Dick Cavett, Marlon Brando, Ron Galella, Truman Capote

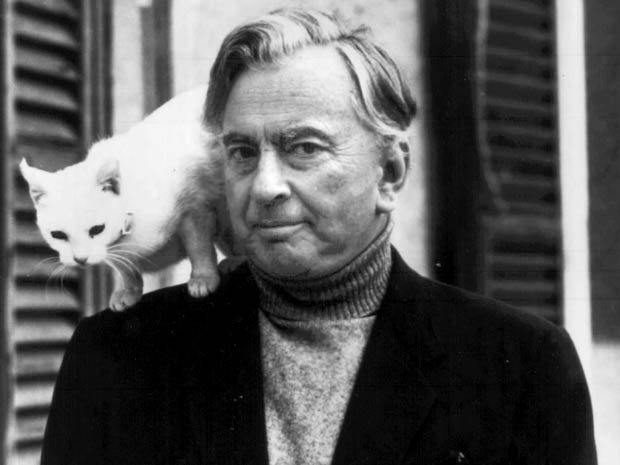

Hersey wrote an aftermath to "Hiroshima" 40 years later, tracing the fates of the six survivors he originally interviewed. (Photo by Carl Van Vechten.)

Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood and John Hersey’s Hiroshima are the two best pieces of long-form American nonfiction I have ever read. I wouldn’t change a word of either one. Hersey’s work, which he wrote for his longtime employer, The New Yorker, was so brilliantly shattering that the entire August 31, 1946 issue was dedicated solely to the article. It became an instant classic and so did the subsequent book version.

Although he was always best know for this piece during his life, Hersey turned out a formidable quantity of other quality fiction and nonfiction. A 1989 Vintage collection, Life Sketches: Incisive and Profoundly Insightful Portraits of Extraordinary Men and Women, 1944-1989, brought together some of Hersey’s finest biographical articles.

The 1945 piece, “The Brilliant Jughead,” tells the story of Private John Daniel Ramey, an illiterate U.S. soldier who was sent to a special training unit in Pennsylvania that conducted a highly successful three-month basic literacy course. This unit, and others like it, taught more than a quarter million illiterate servicemen–who were labeled with the pejorative “jughead” by some fellow soldiers–to read and write during WWII. An excerpt:

“Private Ramey, who was assigned to the Pennsylvania school toward the end of March, 1945, could hardly be called a typical jughead. There is, in fact, no typical illiterate, any more than there is a typical college graduate. Ramey is above whatever average there is. He finished the course, which usually takes twelve weeks, in ten. By jughead standards, Ramey is brilliant. He says that he was often embarrassed, when he was a civilian, by not being able to read and write, but the surprising thing about his life before the war is how much he, an illiterate, was able to do for himself: at one time he owned a house, ran a small coal mine employing twenty-eight men, and had two automobiles, the better of which was a Mercury with, as he says, ‘one of them cloth tops on it,’ bought brand-new. The fact that he is above average makes him especially grateful for the opportunities, the amazements, opened up for him by being educated, for the first time in his life, to the written word.”

Not just content to be a huge flop at the box office, John Huston’s quasi-farce Beat the Devil was the kind of huge flop that annoyed people. That’s because the screenplay, which Huston co-wrote with Truman Capote, played with the conventions of genre film at a time when you didn’t do that sort of thing, especially with a huge, bankable star like Humphrey Bogart. The way the film plays with form might seem subtle today, but it was jarring in 1953.

Billy Dannreuther (Bogart) is a grifter with a heart of gold, hoping to strike it rich with a dubious land deal in Africa. He’s briefly stranded in Italy with his eccentric wife (Gina Lollobrigida) and a quartet of cutthroat rogues. Before he and his crew can find a sober ship captain to take them on their voyage, Billy becomes acquainted with a charming British couple (Jennifer Jones and Edward Underdown), who may or may not be landed gentry. The seemingly innocent pair complicate Dannreuther’s life in ways he can’t anticipate.

Huston and company aren’t shy about letting you know that the plot–something about acquiring acreage rich with uranium–isn’t exactly their greatest concern. The director would rather focus on sharp dialogue and comic turns from his amazing supporting cast (Robert Morley, Peter Lorre, Ivor Bernard, Marco Tulli), who are hilariously pathetic even at their most menacing. Beat the Devil isn’t a great film, but it’s an interesting one to see because it’s the prototype of the kind of movie that the Coen brothers would ultimately perfect. (Available through Netflix and other outlets.)

More Film posts:

- New DVD: Crazy Heart.

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: All the Vermeers in New York. (1989)

- Classic DVD: “La Jetée.” (1962)

- New DVD: The T.A.M.I. Show.

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Bad Company (1972)

- New DVD: The Maid.

- Classic DVD: The Other (1972).

- New DVD: Shutter Island.

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: The Naked Kiss (1964).

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: “La Soufriere” (1976).

- New DVD: The Road.

- Classic DVD: Network (1976).

- Top 20 Films of the Aughts.

- Classic DVD: Seconds (1966).

- New DVD: Art & Copy.

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: The Honeymoon Killers (1970).

- New DVD: Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans.

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Electra Glide in Blue (1973).

- Strange, Small & Forgotten Films: Prime Cut (1972).

Tags: Humphrey Bogart, Ivor Bernard, John Huston, Marco Tulli, Peter Lorre, Robert Morley, Truman Capote

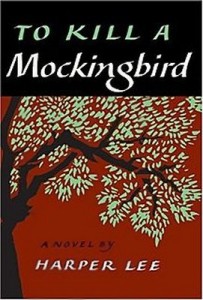

With the 50th anniversary of the publication of To Kill a Mockingbird upon us, some brainiac from the Daily Mail thought it was a good idea to show up unannounced and bother novelist Harper Lee for an interview, even though Lee hasn’t been interested in doing that kind of thing for more than 45 years. The reporter was politely rebuffed. Good for Lee. Back when she was open to discussing her work, Lee sat down with Roy Newquist in 1964 and covered many topics, including the then-state of contemporary writing. An excerpt:

“Roy Newquist: When you look at American writing today, perhaps American theatre too, what do you find that you most admire? And, conversely, what do you most deplore?

Harper Lee: Let me see if I can take that backward and work into it. I think the thing that I most deplore about American writing, and especially in the American theatre, is a lack of craftsmanship. It comes right down to this—the lack of absolute love for language, the lack of sitting down and working a good idea into a gem of an idea. It takes time and patience and effort to turn out a work of art, and few people seem willing to go all the way.

I see a great deal of sloppiness and I deplore it. I suppose the reason I’m so down on it is because I see tendencies in myself to be sloppy, to be satisfied with something that’s not quite good enough. I think writers today are too easily pleased with their work. This is sad. I think the sloppiness and haste carry over into painting. The search, such as it is, is on canvas, not in the mind.

But back to writing. There’s no substitute for the love of language, for the beauty of an English sentence. There’s no substitute for struggling, if a struggle is needed, to make an English sentence as beautiful as it should be.

Now, as to what I think is good about writing. I think that right now, especially in the United States, we’re having a renaissance of the novel. I think that the novel has come into its own, that it has been pushed into its own by American writers. They have widened the scope of the art form. They have more or less opened it up.

Our writers, Faulkner, for instance, turned the novel into something Wolfe was trying to do. (They were contemporaries in a way, but Faulkner really carried out the mission.) It was a vision of enlargement, of using the novel form to encompass something much broader than our friends across the sea have done. I think this is something that’s been handed to us by Faulkner, Wolfe, and possibly (strangely enough) Theodore Dreiser.

Dreiser is a forgotten man, almost, but if you go back you can see what he was trying to do with the novel. He didn’t succeed because I think he imposed his own limitations.

All this is something that has been handed to us as writers today. We don’t have to fight for it, work for it; we have this wonderful literary heritage, and when I say “we” I speak in terms of my contemporaries.

There’s probably no better writer in this country today than Truman Capote. He is growing all the time. The next thing coming from Capote is not a novel—it’s a long piece of reportage, and I think it is going to make him bust loose as a novelist. He’s going to have even deeper dimension to his work. Capote, I think, is the greatest craftsman we have going.

Of course, there’s Mary McCarthy. You may not like her work, but she knows how to write. She knows how to put a novel together. Then there’s John Cheever—his Wapshot novels are absolutely first-rate. And in the southern family there’s Flannery O’Connor.

Of course, there’s Mary McCarthy. You may not like her work, but she knows how to write. She knows how to put a novel together. Then there’s John Cheever—his Wapshot novels are absolutely first-rate. And in the southern family there’s Flannery O’Connor.

You can’t leave out John Updike—he’s so happily gifted in that he can create living human beings. At the same time he has a great respect for his language, for the tongue that gives him voice. And Peter De Vries, as far as I’m concerned, is the Evelyn Waugh of our time. I can’t pay anybody a greater compliment because Waugh is the living master, the baron of style.

These writers, these great ones, are doing something fresh and wonderful and powerful: they are exploring character in ways in which character has never been explored. They are not structured in the old patterns of hanging characters on a plot. Characters make their own plot. The dimensions of the characters determine the action of the novel.”

Tags: Evelyn Waugh, Flannery O'Connor, Harper Lee, John Cheever, John Updike, Mary McCarthy, Peter De Vries, Roy Newquist, Theodore Dreiser, Thomas Wolfe, Truman Capote, William Faulkner

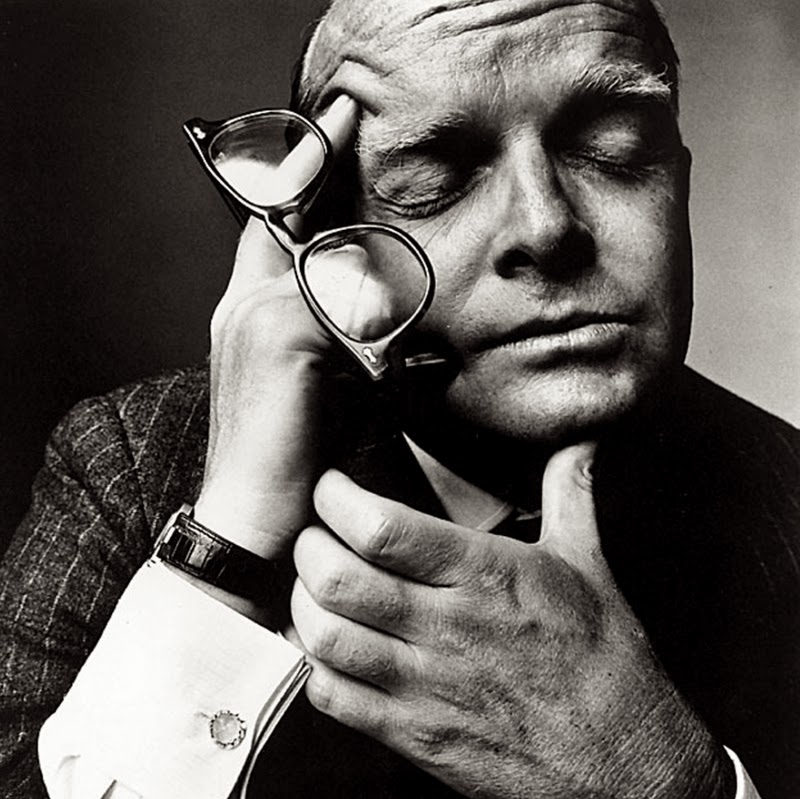

When I was a kid, I saw a really wasted Capote in the Port Authority, trying to get an indifferent homeless woman to talk to him. He was wearing a straw hat. (Image by Roger Higgins.)

In a 1957 interview with the Paris Review, Truman Capote described how he created a comfort zone for himself when writing:

“Paris Review: What are some of your writing habits? Do you use a desk? Do you write on a machine?

Truman Capote: I am a completely horizontal author. I can’t think unless I am lying down, either in bed or stretched on a couch lying down and with a cigarette and coffee handy. I’ve got be puffing and sipping. As the afternoon wears on, I shift from coffee to mint tea to sherry to martinis. No, I don’t use a typewriter. Not in the beginning, I write my first version in longhand (pencil). Then I do a complete revision, also in longhand. Essentially, I think of myself as a stylist, and stylists can become enormously obsessed with the placing of a comma, the weight of a semicolon. Obsessions of this sort, and the time I take over them, irritate me beyond endurance.”

Tags: Truman Capote

Siegel once asked Marlo Thomas if people thought she was "bitchy." She was understandably not very amused. (Image by Ronni Bennett.)

Back before American media was engulfed in its faux-reality mania, in which emotionally damaged recruits are encouraged to act out every last pathology to pump up the ratings, TV host Stanley Siegel and his questionable taste and utter neuroses were considered controversial. During the 1970s, his raucous live morning show on the local ABC affiliate made his name as famous in New York as any politician, athlete or Broadway star.

Siegel invited his therapist to psychoanalyze him each week on the air, he allowed a wasted Truman Capote to sit down as a guest when he was clearly in no condition to do so and he angered a good number of politicos and entertainers with his brash questions. He was the anti-Brokaw, and it worked wonderfully well for a while.

In the 1977 New York magazine article, “Give Us a Kiss, Stanley,” which was written by the journalist and playwright Jonathan Reynolds, Siegel was analyzed a little bit more. These days the talking head appears to be attempting to get some sort of travel show off the ground, but Reynolds’ piece captures Siegel at the height of his entertaining narcissism. An excerpt:

“Every day, Siegel wallows guiltlessly in his own persona, exulting in the dust, high jinx and cobwebs he reveals. He is funny, frightened, confused, weepy, sexual, evangelistic, and overbearing right in front of everybody’s eyes. In terms of emotional exhibitionism, Stanley Siegel makes Jack Paar look like Thomas Pynchon.

In the nearly two years he has been on WABC-TV at 9am, he has sextupled the ratings of his dreary predecessors, increased WABC’s rate card from $35 to $100 for every 30-second spot sold, knocked the venerable Not for Women Only and mega-venerable Concentration out of their time slots, and gained a host of admirers from Robert Evans to Eleanor Holmes Norton.

People tune in to the Stanley Siegel Show to see how Stanley feels–for if there is one predictable element in the program, it is that it will always be clear just how Stanley feels.”

This very non-PC advertisement for Confederate Beach Towels can be seen in the July 1960 issue of Esquire. An appropriate covering for the Jesse Helms Sand Castle Tournament, this wrap cost $4.95. The copy promises: “You don’t have to risk Yankee gunfire to cover yourself with glory on this quality 6′ by 3′ Cannon beach towel with the stars and bars ingrained in blazing red, white and blue.”

Printed on large Life-size paper, this 152-page issue was a special edition that focused exclusively on New York City. Despite a formidable roster on contributors (James Baldwin, Truman Capote, Salvador Dali, etc.), it’s not a particularly inspired issue. Publisher Arnold Gingrich had yet to appoint Harold Hayes as Editor-in-Chief. (Both Hayes and legendary New York magazine founder Clay Felker were already on the masthead.) After Hayes ascension to the top post, he would team with designer George Lois to make Esquire during the ’60s arguably the best American magazine in the history of the business.

Tags: Arnold Gingrich, Clay Felker, Confederate Flag, Esquire, Harold Hayes, james Baldwin, Jesse Helms, Salvador Dali, Truman Capote