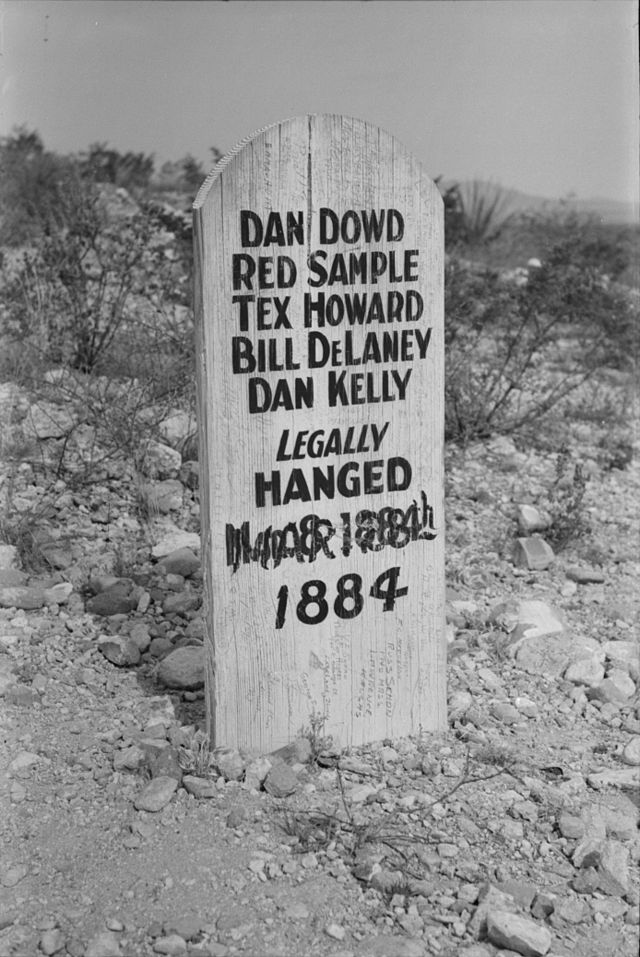

I haven’t yet read Oakley Hall’s McCarthy Era Western, Warlock, but now I must. That’s the book Thomas Pynchon named in 1965 when Holiday magazine asked him to suggest an underappreciated title to its readers. It’s set in 1880s Tombstone, Arizona, which Pynchon believed to be Arthurian in stature. Here’s what he wrote about it:

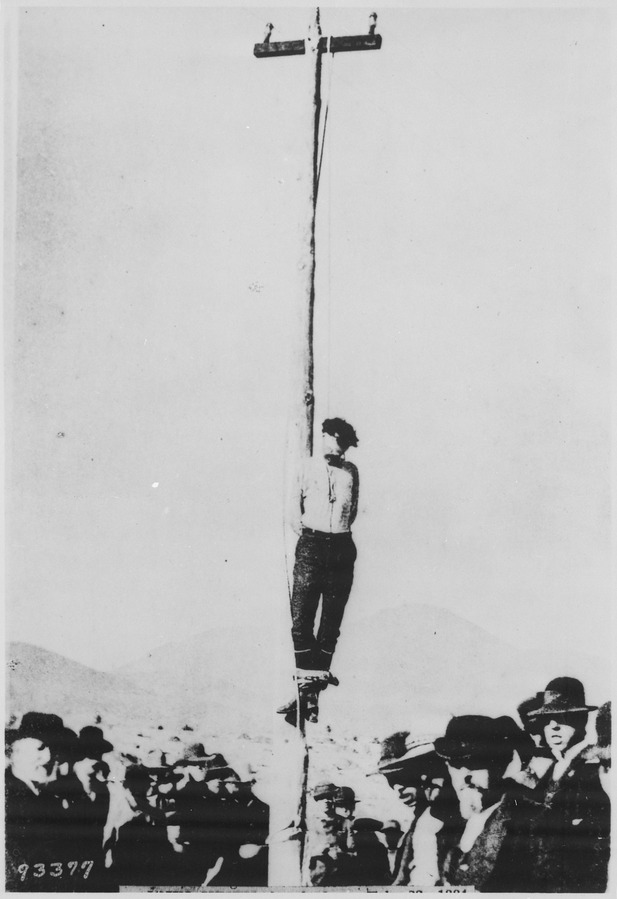

Tombstone, Arizona, during the 1880’s is, in ways, our national Camelot; a never-never land where American virtues are embodied in the Earps, and the opposite evils in the Clanton gang; where the confrontation at the OK Corral takes on some of the dry purity of the Arthurian joust. Oakley Hall, in his very fine novel Warlock(Viking) has restored to the myth of Tombstone its full, mortal, blooded humanity. Earp is transmogrified into a gunfighter named Blaisdell who, partly because of his blown-up image in the Wild West magazines of the day, believes he is a hero. He is summoned to the embattled town of Warlock by a committee of nervous citizens expressly to be a hero, but finds that he cannot, at last, live up to his image; that there is a flaw not only in him but also, we feel, in the entire set of assumptions that have allowed the image to exist. It is Blaisdell’s private abyss, and not too different from the town’s public one. Before the agonized epic of Warlock is over with—the rebellion of the proto-Wobblies working in the mines, the struggling for political control of the area, the gunfighting, mob violence, the personal crises of those in power—the collective awareness that is Warlock must face its own inescapable Horror: that what is called society, with its law and order, is as frail, as precarious, as flesh and can be snuffed out and assimilated back into the desert a easily as a corpse can. It is the deep sensitivity to abysses that makes Warlock, I think, one of our best American novels. For we are a nation that can, many of us, toss with all aplomb our candy wrapper into the Grand Canyon itself, snap a color shot and drive away; and we need voices like Oakley Hall’s to remind us how far that piece of paper, still fluttering brightly behind us, has to fall.

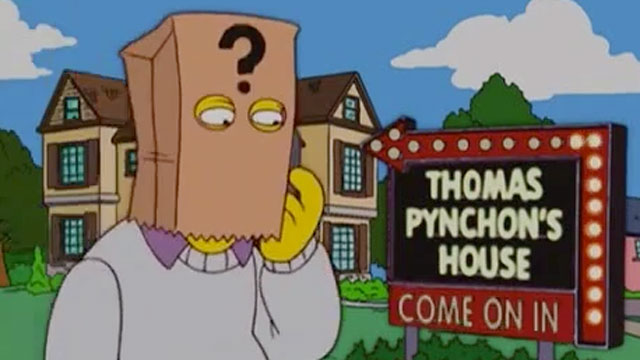

—Thomas Pynchon•