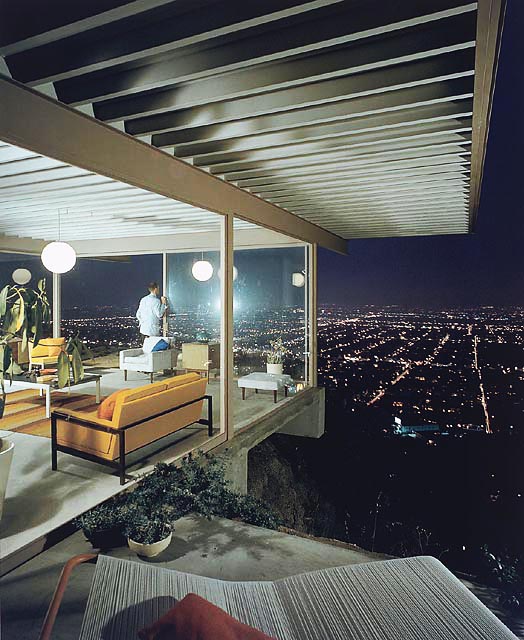

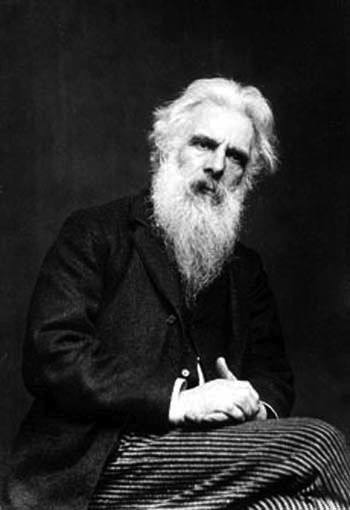

Another new item about one of my favorite movies, Los Angeles Plays Itself, this one a Q&A with director Thom Andersen conducted by Standard Culture. An excerpt about the differences between celluloid Los Angeles and New York City and the actual cities:

“Question:

How are New York and Los Angeles represented differently in movies?

Thom Andersen:

It’s a big question. When sound came in [to film], there was an influx of New York writers to Los Angeles, so there were many, many films set in the NY, although they were filmed in Los Angeles, mostly on stages. They created this picture of New York as this magical city. And that kind of romanticizing of a city never happened with Los Angeles except in some movies made by directors who came from other places for whom Los Angeles was a magical city. For local filmmakers, Los Angeles had a more mixed feeling — something that seems to continue to the present day. There’s something about New York that lends itself to representation on film. It may be simply the fact, as Rem Koolhaas said: it’s a city based on a culture of congestion. Whereas LA is a culture of dispersion, which make it harder to represent on film.

Question:

Do you prefer New York or Los Angeles?

Thom Andersen:

Los Angeles is an easier place to get things done, but to me, New York is still the center of the world. People look better there. They’re smarter. The sunshine here has fried peoples’ brains.”