Centralized mass media, controlled by few hands, had its sense of order usurped by the anarchy and interaction of the Internet, and now that demon energy, with all its good and bad, is nearly ready to be brought to the literal world from the virtual one–a rough beast slouching towards Bethlehem to be born. Will what is acceptable on a flat screen be so in 3D? Will all the many great things be undone by a few terrible ones? What is our direction and can we direct it?

A little bit about the idealistic and naive origins of the movement from Theodore Roszak’s 1985 essay, “From Satori to Silicon Valley“:

“Throughout the later seventies, many of the inventors and entrepreneurs-to-be of the rising personal computer industry were meeting along the San Francisco peninsula in funky town meetings where high-level technical problems and solutions could be swapped like backwoods lore over the cracker barrel of the general store. They adopted friendly, folksy names for their early efforts like the Itty Bitty Machine Company (an alternative IBM), or Kentucky Fried Computers, or the Homebrew Computer Club. Stephen Wozniak was one of the regulars at Homebrew, and when he looked around for a name to give his brainchild, he came up with a quaintly soft, organic identity that significantly changed the hard-edged image of high tech: the Apple. One story has it that the name was chosen by Steven Jobs in honor of the fruitarian diet he had brought back from his journey to the mystic East. The name also carried with it an echo of the Beatles spirit. And, in an effort to keep that spirit alive, Apple made the last heroic attempt to stage a big, outdoor rock gathering: the US Festivals of 1982 and 1983, on which Wozniak spent $20 million of his own money.

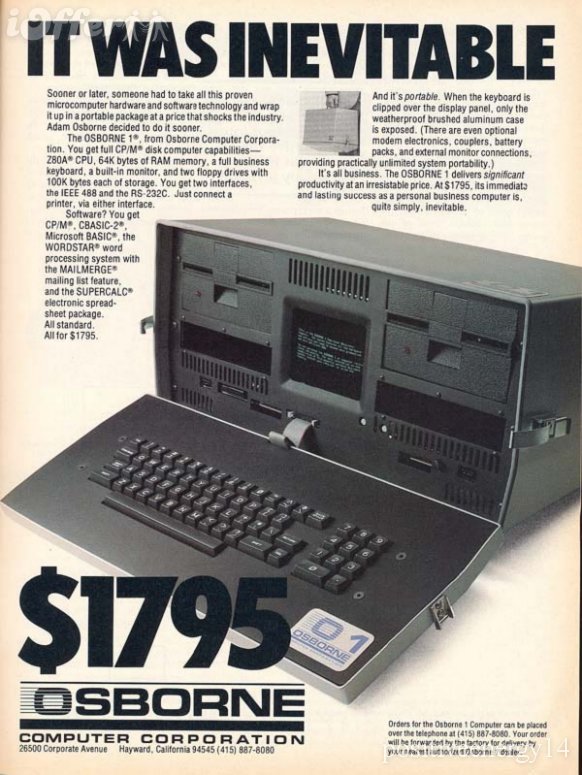

For the surviving remnants of the counter culture in the late seventies, it was digital data, rather than domes, arcologies, or space colonies, that would bring us to the postindustrial promised land. The personal computer would give the millions access to the databases of the world, which — so the argument went — was what they needed in order to become a self-reliant citizenry. The home computer terminal became the centerpiece of a sort of electronic populism. Computerized networks and bulletin boards would keep the tribes in touch, exchanging the vital data that the power elite was denying them. Clever hackers would penetrate the classified databanks that guarded corporate secrets and the mysteries of state. Who would have predicted it? By way of IBM’s video terminals, AT&T’s phone lines, Pentagon space shots, and Westinghouse communications satellites, a worldwide, underground community of computer-literate rebels would arise, armed with information and ready to overthrow the technocratic centers of authority. They might even outlast the total collapse of the high industrial system that had invented their technology. Surely one of the zaniest expressions of the guerrilla hacker worldview was that of Lee Felsenstein, a founder of the Homebrew Computer Club and of Community Memory, later the designer of the Osborne portable computer. Felsenstein’s technological style — emphasizing simplicity and resourceful recycling — arose from an apocalyptic vision of the industrial future that might have come straight out of A Canticle for Liebowitz. He worked from the view ‘that the industrial infrastructure might be snatched away at any time, and the people should be able to scrounge parts to keep their machines going in the rubble of the devastated society; ideally, the machine’s design would be clear enough to allow users to figure out where to put those parts.’ As Felsenstein once put it, ‘I’ve got to design so you can put it together out of garbage cans.’

It is important to appreciate the political idealism that underlay the home computer in its early days, and to recognize its link with tendencies that were part of the counter culture from the beginning. It is quite as important to recognize that the reversionary-technophiliac synthesis it symbolizes is as naive as it is idealistic. So much so that one feels the need of probing deeper to discover the secret of its strange cogency. For how could anyone believe something so unlikely?”