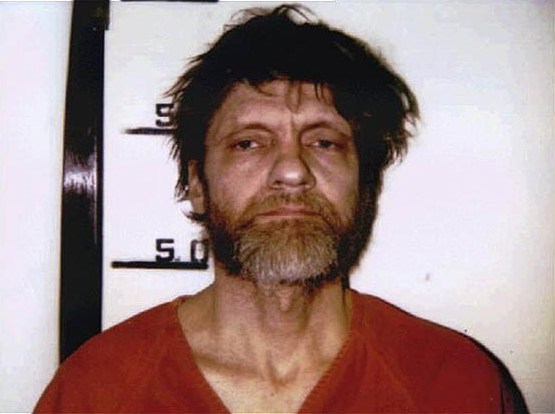

Stephen Hawking and Ted Kaczynski agree: Machine intelligence may be the death of us. Of course, the Unabomber could himself kill you if only he had your snail-mail address.

Found in the Afflictor inbox an offer from a PR person for a free copy of Anti-Tech Revolution: Why and How, Kaczynski’s new book. The release describes the author as a “social theorist and ecological anarchist,” conveniently leaving a few gaps on the old résumé: serial killer, maimer, domestic terrorist, etc.

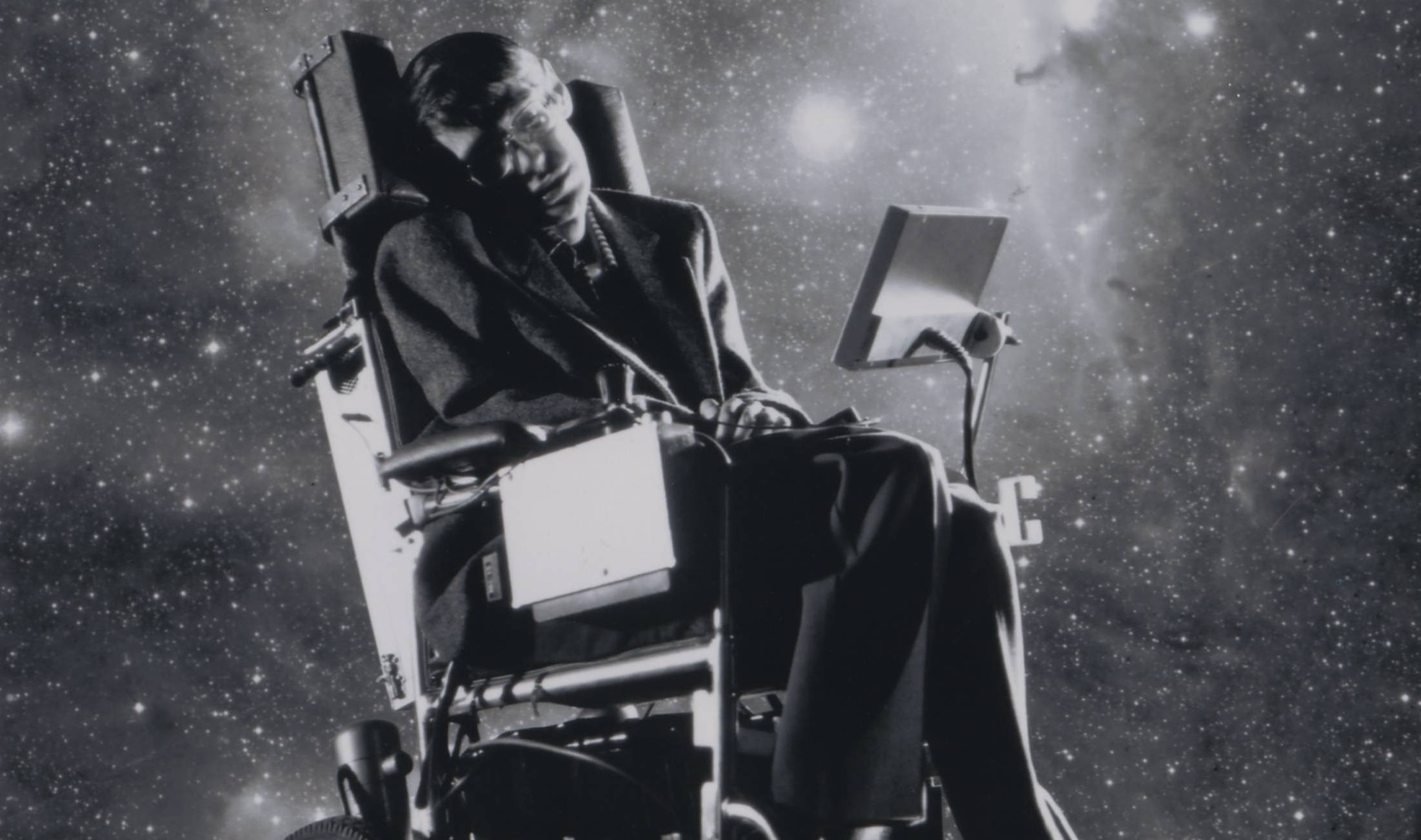

A few minutes later, I read Hawking’s inaugural speech at the new Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence at Cambridge, an institution created to deal sanely and non-violently with the potential problem of humanity being extincted by its own cleverness.

An excerpt from each follows.

From Kaczynski:

People would bitterly resent any system to which they belonged if they believed that when they grew old, or if they became disabled, they would be thrown on the trash-heap.

But when all people have become useless, self-prop systems will find no advantage in taking care of anyone. The techies themselves insist that machines will soon surpass humans in intelligence.119 When that happens, people will be superfluous and natural selection will favor systems that eliminate them—if not abruptly, then in a series of stages so that the risk of rebellion will be minimized.

Even though the technological world-system still needs large numbers of people for the present, there are now more superfluous humans than there have been in the past because technology has replaced people in many jobs and is making inroads even into occupations formerly thought to require human intelligence.120 Consequently, under the pressure of economic competition, the world’s dominant self-prop systems are already allowing a certain degree of callousness to creep into their treatment of superfluous individuals. In the United States and Europe, pensions and other benefits for retired, disabled, unemployed, and other unproductive persons are being substantially reduced;121 at least in the U.S., poverty is increasing; and these facts may well indicate the general trend of the future, though there will doubtless be ups and downs.

It’s important to understand that in order to make people superfluous, machines will not have to surpass them in general intelligence but only in certain specialized kinds of intelligence. For example, the machines will not have to create or understand art, music, or literature, they will not need the ability to carry on an intelligent, non-technical conversation (the “Turing test”), they will not have to exercise tact or understand human nature, because these skills will have no application if humans are to be eliminated anyway. To make humans superfluous, the machines will only need to outperform them in making the technical decisions that have to be made for the purpose of promoting the short-term survival and propagation of the dominant self-prop systems. So, even without going as far as the techies themselves do in assuming intelligence on the part of future machines, we still have to conclude that humans will become obsolete.•

From Hawking:

It is a great pleasure to be here today to open this new Centre. We spend a great deal of time studying history, which, let’s face it, is mostly the history of stupidity. So it is a welcome change that people are studying instead the future of intelligence.

Intelligence is central to what it means to be human. Everything that our civilisation has achieved, is a product of human intelligence, from learning to master fire, to learning to grow food, to understanding the cosmos.

I believe there is no deep difference between what can be achieved by a biological brain and what can be achieved by a computer. It therefore follows that computers can, in theory, emulate human intelligence — and exceed it.

Artificial intelligence research is now progressing rapidly. Recent landmarks such as self-driving cars, or a computer winning at the game of Go, are signs of what is to come. Enormous levels of investment are pouring into this technology. The achievements we have seen so far will surely pale against what the coming decades will bring.

The potential benefits of creating intelligence are huge. We cannot predict what we might achieve, when our own minds are amplified by AI. Perhaps with the tools of this new technological revolution, we will be able to undo some of the damage done to the natural world by the last one — industrialisation. And surely we will aim to finally eradicate disease and poverty. Every aspect of our lives will be transformed. In short, success in creating AI, could be the biggest event in the history of our civilisation.

But it could also be the last, unless we learn how to avoid the risks. Alongside the benefits, AI will also bring dangers, like powerful autonomous weapons, or new ways for the few to oppress the many. It will bring great disruption to our economy. And in the future, AI could develop a will of its own — a will that is in conflict with ours.

In short, the rise of powerful AI will be either the best, or the worst thing, ever to happen to humanity. We do not yet know which.

That is why in 2014, I and a few others called for more research to be done in this area. I am very glad that someone was listening to me!

The research done by this centre is crucial to the future of our civilisation and of our species. I wish you the best of luck!•