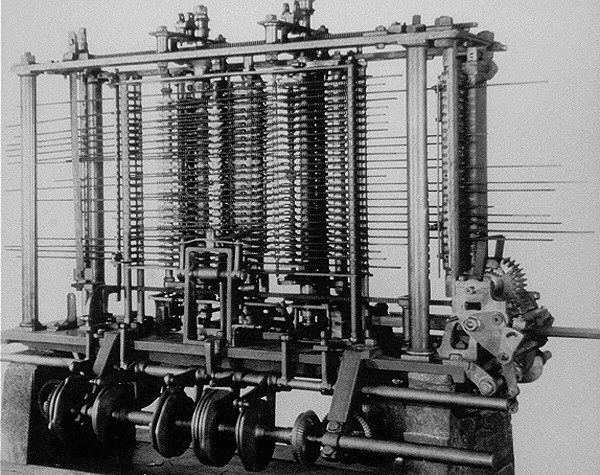

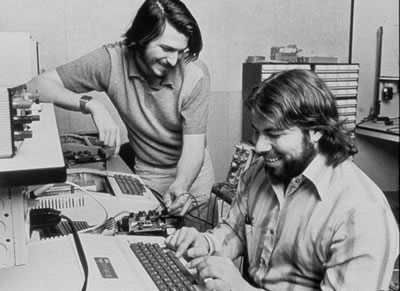

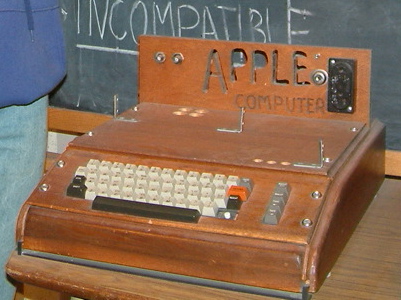

Innovation, that word which is appropriate sparingly but ascribed constantly, is truly the proper description for the work of inventor Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace, a one-woman Jobs and Woz. As Steven Johnson points out in his latest book, How We Got to Now, excerpted in a Financial Times article, new inventions usually are born to many parents working within the same base of knowledge, but the Victorian duo thought completely outside of the box, leaping a full century ahead of everyone else with their ideas about computers. From the FT:

“Most important innovations – in modern times at least – arrive in clusters of simultaneous discovery. The conceptual and technological pieces come together to make a certain idea imaginable – artificial refrigeration, say, or the lightbulb – and around the world people work on the problem, and usually approach it with the same fundamental assumptions about how it can be solved.

Thomas Edison and his peers may have disagreed about the importance of the vacuum or the carbon filament in inventing the electric lightbulb, but none of them was working on an LED. As the writer Kevin Kelly, co-founder of Wired magazine, has observed, the predominance of simultaneous, multiple invention in the historical record has interesting implications for the philosophy of history and science: to what extent is the sequence of invention set in stone by the basic laws of physics or information or the biological and chemical constraints of the environment?

If simultaneous invention is the rule, what about the exceptions? What about Babbage and Lovelace, who were a century ahead of just about every other human on the planet? Most innovation happens in the present tense of possibility, working with tools and concepts that are available in that time. But every now and then an individual or group makes a leap that seems almost like time travelling. What allows them to see past the boundaries of the adjacent possible, when their contemporaries fail to do so? That may be the greatest mystery of all.”